In 1962, Theodor Adorno famously concluded a series of debates with Walter Benjamin by arguing against all directly political art as ineffective: “This is not a time for political art, but politics has migrated into autonomous art, and nowhere more than where it appears to be politically dead.”1 This observation came to mind as I was viewing The Puppet Show, curated by Ingrid Schaffner and Carin Kuoni. The exhibition begins with a video by Bruce Nauman, Violent Incident (Man/Woman Segment) (1986), displayed in an improvised entrance foyer that isolates it from the rest of the exhibition. As the exhibition’s introductory piece, the Nauman video announces that the concept of puppetry will not be limited to the familiar folk-art artifact, but will rather concern the self’s lack of agency, or what Adorno called “a highly concrete historical reality: the abdication of the subject.”2

The elements of this single-channel video are a table set for a romantic dinner, a man, and a woman. The man graciously pulls out a chair for the woman, but as she is about to sit, he is apparently seized by a counter-impulse, and pulls the chair out from under her, so that she falls on the floor. This sets in motion a series of movements and counter-movements: she vengefully reaches up from the floor to stick a finger in his ass, he reacts by cursing, “Fucking cunt, don’t you ever….” They stand facing each other, and he seems about to hit her, when she throws a glass of water in his face. He slaps her; she thrusts her knee in his crotch; he grabs a knife from the table and plunges it in her stomach. Before collapsing, she grabs it back and knifes him, and he collapses. This routine is repeated for thirty minutes.

The repetitions emphasize the involuntary impulses that lie beneath the romantic dinner. Specifically, sexual or self-protective feelings are not subject to the individual’s control. But this lack of agency is no longer the result of repressiveness that causes sexual drives to become tyrannical dissociated complexes, as Freud argues in “The Uncanny,” one of the exhibition’s conceptual antecedents.3 Nauman’s video represents the current phase of the self’s psychic organization, where impulses are not so much repressed as subject to social manipulation. Man and Woman in the video, avatars of the timeless puppet dyad Punch and Judy, can no more stop their behavior than we can stop the video from repeating. We are united with them in our helplessness in the face of social imperatives that the culture industry serves particularly well. As Adorno and Horkheimer wrote of Punch and Judy’s 20th century kin, Donald Duck:

In so far as cartoons do any more than accustom the senses to the new tempo, they hammer into every brain the old lesson that continuous friction, the breaking down of all individual resistance, is the condition of life in this society.4

Nauman’s video frames and isolates this effect of movies in general, their deployment of a social dictum against “individual resistance.” As if in testimony to this difficult message, as I was watching the video, I overheard one museum worker telling another that before the earphones were hooked up, the repeated grunts, screams, curses and thumps of Violent Incident (Man/Woman Segment) had been unbearable to her. Even with the earphones attached, Los Angeles critics have had a similar negative response to the show as a whole, with one reviewer devoting four paragraphs to complaints about the exhibition’s noisiness, which was “nightmarish,” “relentless,” and “arbitrary.”5 For another reviewer, the show is not “magical,” but “largely unaffecting” and “inert.”6

The Puppet Show is both inert and noisy; these adjectives characterize the two media and psychic poles around which the show is organized. Video in the show generally represents the noisy, often a repetition compulsion of speech or movement, while sculpture represents the inert, or a stunting of the self. (The few photographs included in the exhibition are of sculpture.) “Inert” is the inner condition of the subject who, as in a Beckett play, is just alive enough to know he/she is dead. “Noisy” is a futile attempt to overcome the stunting and exercise agency. Causes of the stunting are laid out in pieces that refer explicitly to history, such as Kara Walker’s or William Kentridge’s, where the puppeteers are vicious slave-owners or dictators. These works lend their narratives to compressed suggestions of systemic cruelty in masterworks by Kelley, Bourgeois, and Nauman, among others, works that appear to be “politically dead,” but which comprise the exhibition’s provocative core.

As I enter the main gallery, there are large wooden crates, open on one side, housing videos. Otherwise, the space is dominated by four large sculptures, the most compelling of which are Mike Kelley’s Gussied Up (1992) and Louise Bourgeois’s Untitled (1996). Kelley’s is the largest, consisting of a roughly 10 x 20 foot plank made of plywood, standing on sawhorses, on top of which is full-sized furniture made of polished wood: a four poster bed, 2 chairs, one coffee table. There are also a goblet and a table clamp. Sixteen pieces of children’s clothing—knit caps, sweaters, shorts and the like—“dress” the furniture, construing the furniture legs, arms, and posts as figures.

This childlike installation, while evoking fairytales about miniature peoples, portrays an American blue-collar family whose miserable puppet show life is enacted on the stage of an improvised workbench, who would use the words “gussied up,” and whose polished wood furniture recalls a pre-capitalist country life of workmanship, old values, and old ways, like getting dressed up for church or a dance. But those values are no longer operative, if they ever were, and the furniture is clearly mass produced and probably second-hand. Now some convergence of commodification and poverty has reduced the family to the status of objects. There are no parents (no adult size clothing) and the children are stubs of wood. Parental aesthetic imperviousness, expressed in the awkward furniture arrangement, operates as a cipher for emotional neglect. And worse: one tiny jacket is tightly squeezed in the table clamp; the twisting and stretching of the little clothes over the furniture parts express torture or abuse. Interestingly, this piece excludes the stereotypical ugliness of American working class life: there are no bright colors, no T.V., no bottles of ketchup. It has a simple beauty.

The reduction of the individual to an extreme powerlessness is also the subject of Bourgeois’s Untitled, which features four life-sized stuffed dolls hanging from a black metal “tree,” a pole with four extensions, suggesting both a clothesline and the hanging-tree of U.S. racial history. The dolls too are fusions of race, class and gender references. The heads of two of the figures are small, like those of sock dolls, and black. One is dressed in a button up blue work dress, such as a servant might wear, and the other in a floral day dress that a woman of the bourgeoisie might wear to a garden party. Neither is given the agency of arms or legs. A third figure is not even a doll, but a classic black evening dress on a hanger. The fourth figure is a version of what is subtracted from the dress. Made of pale beige cloth covered with sheer nylon stockings, (with bumps and contours suggesting breasts and female genitals contained within a giant male genital) it is also a torso and what’s left of a self.

Though apparently comparable to Kelley’s wooden stub children, Bourgeois’s damaged dolls refer to a more generalized violence. Kelley’s children are still part of a family, belonging to the same furniture set, as it were, so that the work expresses connectedness (however degraded) among them. The Bourgeois figures are dismembered or butchered, and the figures are connected only in that they have all been hung out to dry. They are the visual embodiment of a statement seemingly issued from the patriarchal heart of America: whether black or white, women are pieces of meat. Put differently, in the Kelley, psychological violence is primary, the precursor of physical violence; in the Bourgeois the two are fused and indistinguishable.

In the catalog essay for The Uncanny (2004), Mike Kelley writes that “…the image of wholeness [is] only a pathetic comment on the lost utopianism of modernism. It is comparable to a kind of acting out of socially expected norms, the presentation of a false ‘true self’….”7 In presenting the true damaged self, the Bourgeois and Kelley pieces, like many sculptures in the show, are poignant because they remain infused with a desire for wholeness, with the idea of a family in the Kelley, and the idea of a sexually vital woman in an evening dress in the Bourgeois. Like the interlude dancer in choreographer Pina Bausch’s Nur Du (1996) whose body seems to attack itself in repudiation of ballet’s false gracefulness (or puppetry), these pieces show that it hurts to give a truthful account. Incompletely reconciled to fragmentation as normative, many of the works in the show seem to struggle against it.

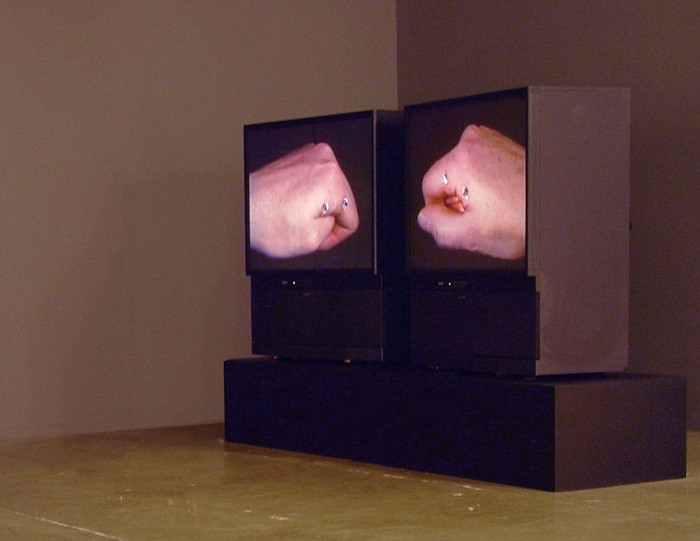

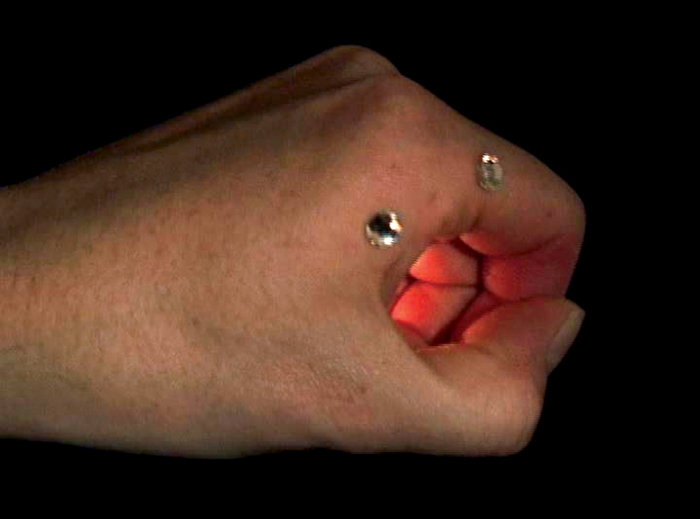

One such piece, a remarkable fusion of the inert and the noisy, is Colloquy (2004) by Cindy Loehr, a two-channel video in which two hands, each with its own monitor, enact a hand puppet show about the end of a relationship. Phrases from the book of couples counseling are produced like one-liners: “You can’t kill me off without killing yourself”; “I don’t want to change who you are but I’m confused”; “Everything I know I learned from you”; and so on. These clichés, expressed in a sincere voice, are counterpoised to the weird but moving gestures of the hand that listens: clenching and relaxing the thumb, tensing all the fingers together until they tremble. This hand suggests early life forms like fish or underwater plants. As body parts standing in for the whole self, they (again) suggest the self is fragmented, stunted, deformed. The dialogue shifts from the interpersonal to the intrapersonal, partly because the rhinestones glued to the hands to suggest eyes have the classic uncanny effect of eyes that do not see. They direct you inward, toward perceiving the platitudes as inner attacks and laments.

Even more inward, and more acutely in dialogue with itself, is Matt Mullican’s Live Under Hypnosis (2002), documentation of a performance consisting of four hypnoses of Mullican enacted in the same space. In the video, Mullican displays childlike behavior, daily routines, fear and wishes. The play between a puppeteer’s control of the strings, and the lack of control affected by the puppet’s weight and construction, is most eerily expressed visually in the first segment: “A. It’s cold in the box,” where a square defined by tape on the floor becomes a tiny theater for a trapped and isolated Mullican.

In the second segment “B. Checking out the space,” Mullican paints a figure, a kind of self-portrait that he’s been trying to capture for years. He says, “The first time I painted this was fifteen to twenty years ago, and I’m still not….” An embellished stick figure, it is more robot than puppet, with antennae in lieu of arms and legs, as if it is trying not so much to move as to transmit or communicate. Eventually the strain effected by these deep inquiries takes its toll, and Mullican in “D. Do not want to hear his voice,” is fed up with his hypnotist, his ostensible puppeteer, and the one who facilitates his work. Overwhelmed by the demands of his art form, Mullican screams “You’re yelling! You’re too loud!” Reminding me of the art critics faced with this challenging exhibition, he covers his ears with a pillow and runs away.

Like several of the works in the show, such as those by Paul McCarthy, Phillip Perrano and Rirkrit Tiravanija, and Dennis Oppenheim, Mullican’s is a portrait of the artist, revealing the challenge of psychic management within the urge to create, when one may be both puppet and puppeteer. Oppenheim’s Theme for a Major Hit (1974) combines the inert and the noisy in alternating acts, with several true puppets (Oppenheim in multiple) hanging from strings. When the music comes on, they dance with clattering intensity, in abandonment that is literally programmed, for we can see the computer that operates them, while the music’s lyrics, “It ain’t what you make, it’s what makes you do it,” mock the notion of agency. Dressed in black or grey suits with white shirts, these puppets could be dancing at a club or climbing the corporate ladder, as is more explicitly true of Maurizio Cattelan’s similarly dressed puppet, which desperately clings to a sheer glass wall.

The overlapping interests of the art world and the corporate world is acknowledged in several works that move from the arena of creation to that of the art market, where others move beyond that to the broader social world. Kara Walker, for example, tells the story of women and slavery, rendering historical narrative in animated cutouts that mimic a halting voice or fragmented memory. Effective as this work is, it packs considerably less power than Bourgeois’s congealed narrative on the same topic. In fact, though the works in the exhibition generally dialogue with and enhance one another, the less polemical pieces seem to mine more deeply the contemporary manifold implications of the puppet, recalling Adorno’s claim for the apparently defeated work of Kafka and Beckett, which “have an effect by comparison with which officially committed works look like pantomime”8—or in this case—puppetry.

Annette Leddy is a Los Angeles writer, archivist, and curator.