We’ve all got our faves… artists or artworks that at one time or another made a distinct and lasting impression. It’s these encounters that challenge our previous notions of what art is or can be and continue to inspire our creative response. Over the years, selected works by both Philip Guston and Giorgio de Chirico have tweaked my own particular muse, so upon hearing that a similar influence lay at the heart of Enigma Variations: Philip Guston and Giorgio de Chirico at The Santa Monica Museum, I felt compelled to see in what way.

As the show’s introductory wall text describes, the young Philip Guston had been a fan of Giorgio de Chirico’s work during his formative years as a young painter in 1920’s Los Angeles. Having seen only black and white reproductions of de Chirico’s work from art magazines, Guston was deeply moved by a face-to-face viewing of de Chirico’s The Soothsayer’s Recompense (1913) in a visit to the Hollywood home of collectors Louise and Walter Arensberg. In Guston’s words, “Seeing these paintings by de Chirico…made me resolve to be, want to be a painter. I felt as if I had come home.”1 A photograph of the Arensbergs’ living room accompanies the aforementioned wall text. In many ways, this reproduction provides one of the more engaging aspects of the show by setting the stage for a unique experience of “seeing” as it relates to identification, inspiration and, in this viewer’s case, loss.

While this large black and white shot of the Arensbergs’ home may not be allegorical in the pictorial sense, it is nevertheless imbued with an ominous quality that I often associate with that same form. With a nod to the repeated use of a similar architectural element found in de Chirico’s The Soothsayer’s Recompense, an enormous archway in the Arensbergs’ home frames the composition and dramatically establishes the point of view. Through this archway, one is drawn-in visually (through sight and perspective) to the Arensbergs’ living room. Dead center within the photograph of the living room lies an open door—another architectural element frequently quoted within the works of both de Chirico and Guston. Directly to the left of that open door hangs de Chirico’s The Soothsayer’s Recompense. By virtue of the painting’s size and architectural resonance to the space, Recompense dominates all else in the Arensbergs’ living room.

A closer look at The Soothsayer’s Recompense reveals a Neo-classical figure lying in repose upon a horizontal slab, or what I first thought to be a divan. Directly under the painting (within the Arensbergs’ living room) sits a similarly proportioned couch. Whether by fluke or by design, this is where the boundaries between the image of the Arensbergs’ room and de Chirico’s painting begin to blur. The distinctions between framed and distant spaces (whether in the painting or in the photograph) creates an odd visual correspondence where one unwittingly expects to see a figure (just like in de Chirico’s Recompense) in repose upon the Arensberg’s couch, except their couch is empty. It’s at this point where one recognizes that there are no figures to be seen anywhere within the photo. And it’s this absence that calls forth a curious presence by, in effect, replacing the now- absent Guston with the now-present viewer.

By stepping into the conditions of Guston’s “moment” with de Chirico’s The Soothsayer’s Recompense, the viewer is asked, in a sense, to participate in a staged re-enactment of inspiration. This psychic role-play comes to its full realization when, as one turns from the photo of the Arensbergs’ to see the exhibition itself, the viewer comes face-to-face with the “real” Soothsayer’s Recompense and the full psychic whammy gets laid on him.“Is it me seeing this painting or is it me as Guston seeing this painting?” Which then leads to, “Whose moment is this?” followed by “Whose inspiration is at stake?” Granted, the breakdown of this reading may be as paranoid as it is hyperbolic, but as I/you/ we/Guston stand there negotiating our respective inspirations, seeing the painting itself becomes an afterthought.

Proceeding in a similar vein to this juxtaposition between the photograph and The Soothsayer’s Recompense, curators Michael R. Taylor and Lisa Melandri employ a series of side-by-side comparisons that show how an assortment of formal and conceptual themes within de Chirico’s paintings find their way into Guston’s works. What many of these comparisons do—in addition to showing a kindred struggle between the two artists with respect to figuration, representation and 20th century angst—is present a series of references in de Chirico’s work for what had previously been for me much of Guston’s more obscure or fucked-up imagery. That imagery’s insistent visceral awkwardness acted almost as a Rorschach in the face of any attempt at interpretation.

What both de Chirico’s and Guston’s paintings have in common is that while we may recognize discrete elements within their respective paintings—stretcher bars, medieval towers, shoes, garbage can lids, torsos, etc.—it’s when these fragments come together within the context of a single painting that they suddenly challenge meaning by their unique association. It’s precisely within the inscrutable nature of their distinct compositions that I find both de Chirico’s and Guston’s work so engaging. “Yup…that really is a hairdoo on a stage that looks like a horizon with what looks like an ear coming out of it next to a stand of trees (or sneakers) with a cloud or glob of green paint…” It all makes perfect sense. Not because any of us have ever seen anything like that, but precisely because within the context of looking at a Guston or a de Chirico, we’ve come to anticipate (and embrace) the experience of it “not” making sense. And when, as is seen in Enigma Variations, an explanation (however minor) does show-up to ground a certain aspect of the work—in effect, making the moment of seeing that work more comprehensible—then I find something valuable becomes lost.

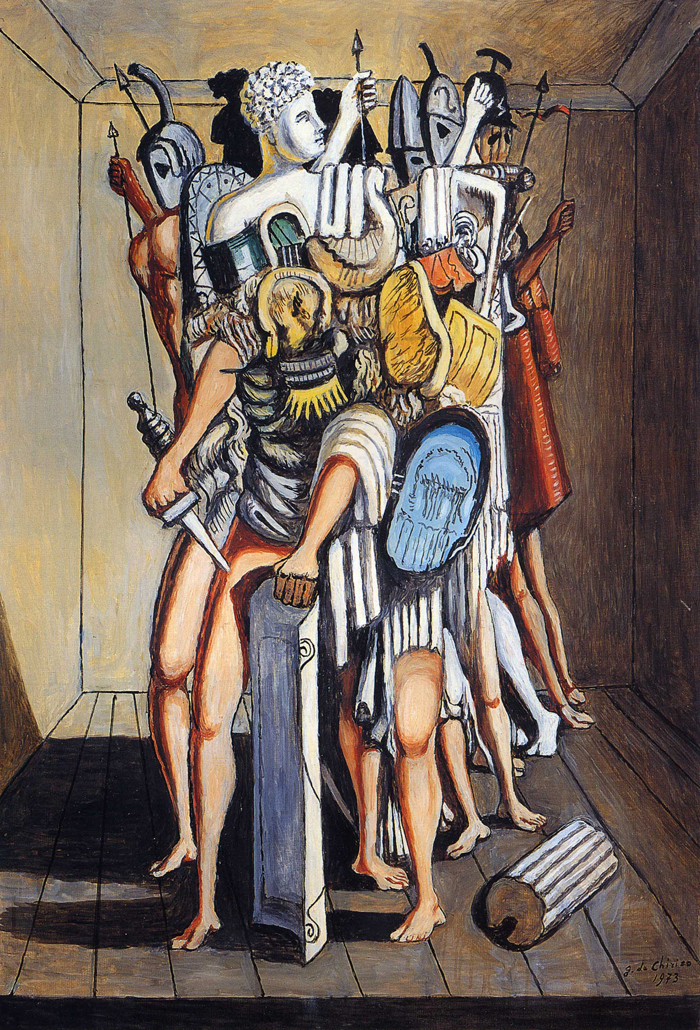

For example, hanging directly next to the previously described “hairdoo painting” by Guston, Untitled (1975), sits de Chirico’s Gladiators After the Battle (1968). The de Chirico is a kitschy painting, crowded with a dozen or so shirtless gladiators (portrayed from the waist up) all having a similarly- painted, curly black hairdoo…a dead ringer for the ‘doo in Guston’s Untitled painting. It’s a trivial comparison, but it’s one that can’t be ignored and it’s one that now inextricably ties the two paintings together through a matrix of appropriation.

It is true that one may often stand to gain something from this type of literal visual correspondence. Works that may have initially been considered to be an artist’s lesser accomplishments (or wholly unrelated) can come off looking far more compelling when situated in context. However, the flip side of this strategy—and what I found to be the over- riding problem with its employment in Enigma Variations—is that it results in a curatorial overshare at the expense of the painting’s themselves, or, more specifically, at the expense of the audience’s ability to experience the works as distinct visual statements.

The most egregious example of this installation strategy lies within the exhibition’s final “one of these things looks like the other” moments, which sets up a comparison between de Chirico’s The Invincible Cohort (1973) and Guston’s Ramp (1979). From this comparison, it’s all too clear that Cohort and Ramp share an uncanny resemblance in their respective compositions. The exhibition’s catalogue reminds us that both de Chirico and Guston were influenced by Renaissance perspective and it’s within this stark comparison where we see this influence realized. Each painting has a receding floor plane, upon which sits a figurative accumulation in the painting’s center. In de Chirico’s case, the “cohort” is a jumble of Neo-Classical gladiators and soldiers brandishing shields and spears. In Guston’s Ramp, we see de Chirico’s tame mishmash transformed into an abject portrait of garbage can lids or mushrooms or targets and cups and newspapers and cigars and obscure pegs and knives and smoke and any other penis and ‘giner references that come to mind. It’s a deliciously juicy, absurd, threatening and unique visual encounter that breathes piss and fire back into traditional portraiture. That is …until it is placed directly next to de Chirico’s Invincible Cohort, where it becomes irrevocably tied to that painting through its literal proximity, its compositional resonance and the formal geneology now presaged in Enigma Variations. All cases make it impossible to see Guston’s Ramp without the echo of de Chirico’s Cohort as referrant… “invincible” as they come.

It may very well be that the sense of loss I experienced in negotiating the curatorial juxtapositions in Enigma Variations is a function of my own internalized belief that Guston’s brilliance is/was the stuff of Modernist mythology—a narrative where inspiration is less a factor of mere mortal influence than a dramatic by-product of angst, booze and the occasional divine lightning bolt. For someone weaned on Postmodern discourse who is continually at odds with the hold that such mythology has within visual culture, it is a revelation to discover its traction within my own bones. In some ways, moments of inspiration are the stuff of mythology in that they are deeply complicated, not only with respect to the effects of that moment on one’s practice, but their reification within cultural discourse. I can’t help but feel that Taylor and Melandri’s approach to presenting Guston’s response to de Chirico’s work comes-off as the labor of dutiful art detectives with the effect of closing down meaning rather than opening-up its potential. By offering the viewer a situation where formal (as well as conceptual) complexity feels somehow sidelined in favor of something as reductive as likeness, then the tendency towards a more expansive definition of meaning (as well as creative agency) begins to suffer. And this is where the enigma in Enigma Variations ultimately exists. By experiencing a profound sense of loss brought about by actually being informed, I suddenly find myself weighing the consequences of that critical inquiry against my preference to “not know.”

Michael Minelli is an artist living and working in L.A. He teaches graduate studies at Vermont College.