Lawrence Weiner, PRIMARY SECONDARY TERTIARY, 2007. Installation view at Padiglione Italia, 52nd International Art Exhibition. Courtesy Lisson Gallery, London. Photo Courtesy of The Moved Pictures Archive.

The rare conjunction, in June 2007, of the 52nd Venice Biennale, the Basel Art Fair, Documenta 12 at Kassel and the 4th Muenster Sculpture Project promised visitors an unprecedented overview of the state of contemporary art–at least, as it is seen from Europe, or, more precisely, from these prominent European vantage points. Despite the instant artworld that has ballooned around its Miami offshoot, Art Basel remains the art fair to beat, and to be at. An ongoing, public debate about “public art,” conducted mostly between the works themselves, and carefully overseen since 1997 by Kasper Koenig, the Muenster Project announced that it would be more archival of previous editions, and more responsive to political orientations and “post-sculptural” forms, than before. There was against-the-grain potential, too, in the fact that the Venice Biennale was, for the first time, under directorship of a North American–New York-based curator, critic and educator Robert Storr. And that the Austrian partnership Roger M. Buergel and Ruth Noack, director and curator respectively of Documenta 12, had issued a set of Magazines, with articles drawn from art journals all over the world that had agreed to explore the exhibition’s hot topics: Is modernity our antiquity? What is bare life? What is to be done?

Both the Venice Biennale and Documenta 12 received a hammering in the first responses of most print journalists, whereas Muenster was warmly welcomed. Guardian writer Adrian Searle is representa- tive. He headlined the “critical inanities” in various national pavilions at Venice–not least Britain’s, which featured a febrile display by Tracey Emin–and the lack of “a genuine flair for exhibition-making” in the main pavilions. Responding to Storr’s admonition that viewers should take in the exhibition slowly, he comments “Slow down too much and we might notice the tired alignments, or how dreary Robert Ryman looks, and how Storr is shaky when it comes to photography and sculpture.” (June 12, 2007). A week later, in Kassel, his review was headed “100 days of ineptitude,” and his overall reaction was blunt: “Documenta 12 is a disaster.” (June 19, 2007). By the time he got to Muenster, he was so relieved to find a focused event, conducted in a spirit of (mostly) unalloyed optimism, that his leader declared it “Not only great–but great fun!” (June 26, 2007). He did not get to the bun-fight at Basel (nor did I–seen one, seen them all) so I will leave the art fair aside.

What causes reactions such as these? Searle is explicit about his starting point: “With a budget approaching $20M, the exhibition lays claim to setting the international artistic agenda: Documenta identifies which artists, living and dead, we should be looking at, what ideas and issues we should be attending to, what problems and opportunities art faces at a given time.” For many decades, the same expectation has been true of Venice, especially in the broad-scale, survey exhibitions presented by the directors in the misnamed Italian Pavilion and in the Arsenale. Carry this expectation to Europe this spring and summer, however, and you are bound to come away disappointed.

My reactions were, basically, the reverse of the reviewers’ consensus. I had come to these mega- shows with, I admit, a question that I hoped would be answered–in new and useful ways–by these exhibitions, and by others in Europe this spring and summer. Or, perhaps, as has so often, so rewardingly happened in my fortunate experience, the answers would be suggested by certain artworks that might appear within them. The question is a big one, having been wrought, during the past decade, with as much care as I can muster. A demanding question, yet wide open as to the kinds of answer it might attract. Here it is: Had the curators and their teams grasped the fact that the overriding concern of contemporary art around the world, the concern most proper to it as contemporary art, is the growing, alarming and inescapable disjunction– experienced by all of us living in the conditions of contemporaneity–between the small-scale, specific yet fragile facts of our everyday lives and the accelerating incomprehensibility, indeed, the often deadly incommen- surability, of competing global world-pictures? If they had seen things this way, did they assemble works by artists able to display at least aspects of the extremely complex architecture of this dislocation, and by those artists able to point us toward the recovery, or discovery, of concrete kinds of locality, timeliness, identity and selfhood?

If you think that this kind of question is too much to ask of an exhibition, then you have ignored the ambition of the Bienal de Habana when it began in 1984, and its actual achievement since 1994, when the curatorial team at the Wifredo Lam Center for Contemporary Art first fully realized a goal of precisely this kind: to show the world, and in particular its region, what, in the aftermath of the Cold War, art from the Third World was like, and how it related to the larger world (dis)order. The first Documenta, in 1955, had aimed to do something similar, albeit on a narrower scale: to reconnect German art to its modernist lineage by reviving its pre-Nazi past, and by linking it to the major currents of avant-garde art in the rest of the West, not least the United States. Since then, Documenta exhibitions have, every five years, striven to intervene in art history. Not only to point up directions for present day art going forward, but also to propose reinterpretations of past art that have, in the minds of the curators, relevance for present practice.

Catherine David’s Documenta 10 of 1997 contained within it revelatory mini-retrospectives such as Helio Oiticica, Michelangelo Pistoletto and Marcel Broodthaers. Young artists everywhere are still busily engaged in exploring the implications of their innovations, and those of artists like them. In 2002, Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta 11 continued this tendency, allotting a central space to Hanne Darboven, but he also, and more powerfully, brought to the center of European art institutions the legacy of Havana, and of Dakar, where a biennale of the arts was first staged in 1992. The visual cultures of the non-aligned states during the Cold War era, the art emergent from the processes of decolonization, have influenced art practice everywhere. This amounts to what he has dubbed “the postcolonial constellation.”

The artworld reaction, in the U.S. especially, and to a different degree in Europe, was swift. These were, after all, the months of the invasion of Iraq, with its “shock and awe” tactics, and rhetoric of U.S. invincibility. Less violently (but in the aftermath of horrible violence) the EEC was undertaking an abrupt expansion in its membership, into the ex-Soviet zones and eastward, while the numbers of those desperately seeking to enter Europe from the global South was rising. The result: alarmed specters of “fortress Europe.” For these and a host of internal artworld reasons (not least the burgeoning of contemporary art into market leadership) curators everywhere retreated towards more aesthetic themes, thrust interpretation into the hands of bemused spectators or stacked on the thematics in “everything goes” arrays. Organizationally, they multiplied into “curatorial teams,” spread the responsibility, and into ducked the spotlight. The Venice Biennale of 2003 fell victim of this rush from judgment.

It echoes still. As you step off the vaparetto at the Giardini entrance to the 52nd Venice Biennale, a sign greets you: “The Biennale has no position on conflict and no part in it. RS.” The initials are those of the Biennale director; the sign uses the Biennale’s signature colors and typography, but it does not include the otherwise ubiquitous logo. Is it one of the countless instances of visual commentary, unofficial intervention, fellow-traveling or outright attention-seeking that the Biennale spawns, in the city and beyond? Afterall, it has already attracted one of the most wishful of these ever present stickers: the Israeli flag, in Palestinian colors. Yet the sign’s sentiment, and its tone, is quintessential Storr: an openhearted, bold assertion of having no position, stout liberalism facing down the ideologies of all stripes that currently besiege it. This spirit drives his introductory essay to the Biennale’s three-catalog set, in which he reminds aesthetes and artworld “professionals and hangers-on” that “biennales are the places where a multiplicity of art worlds meet in the presence of a vast, varied and–contrary to what commentators across the political spectrum have said–avid and unpredictable public.” Thus the exhibition’s one-step-up-from-Disney slogan: “Think with the Senses–Feel with the Mind: Art in the Present Tense.” A similar nervousness about audience appears in the public stance of the Documenta 12 director/curators, right there in their anodyne preface, in such disingenuous remarks as: “It was not our aim either to highlight artist’s names or succumb to all-encompassing concepts, nor did we want to favour geopolitical identity (a la “art from India”).”

Yet the exhibitions on the ground also responded to the fact that, in the past few years, as the world situation has markedly worsened and increasing numbers of artists to return to the fray. In 2006, the 9th Bienal de Habana surveyed the explosive conurbation occurring around cities throughout the world (this was also a sub-theme at the Gwangju Biennale), Charles Merewether’s Biennale of Sydney focused on “Zones of Contact” across and between global cultures, as did (although in a more defined, yet still huge region) the 5th Asia-Pacific Triennial in Brisbane, while Okwui Enwezor’s Bienal de Sevilla highlighted “The Unhomely: Phantom Scenes in Global Society.” The exhibition as argument is back.

The curators in Venice, Kassel and Muenster know this. Their exhibitions, at their best, are responses to the question about locality and world-picturing that I brought with me–or, at least, to their own versions of this question. In 2006, Storr hosted an international forum on the future of biennales, the proceedings of which are yet to appear. His catalog introduction begins with the phrase “Epiphanies happen but do not last.” A warning–in the spirit of Willem de Kooning’s famous remark “Content is a glimpse”–that art’s rewards take time, require labor, and will be ephemeral at best, but are still worth it. And that this configuration of art’s current offering is itself stilled in time, in the tensility of the present. Then, like a mid-nineteenth century critic strolling around a Salon (in this case, juried and hung by himself), he takes the reader on a tour of the exhibition, explaining his major choices, justifying their positioning within the visitor’s itinerary, and highlighting the revelations that he hopes they will release. At Kassel, the catalog contains no such essay; rather, in the now familiar Taschen style, it consists of one-page entries on each work opposite an image of it, set out in chronological order (which is not how the works are hung in the exhibition venues). Accompanying it is a Bilderbuch, filled with photographs that document, allusively, the spaces at these venues as the exhibition was being hung. To find Buergel’s definitive guide to experiencing Documenta 12 you need to read his essay in the first of the magazines, Modernity? It is a detailed and subtle, positively revisionist reading of the display aesthetics of the first Documenta exhibition of 1955. Indirection and inference are the hallmarks of Documenta 12.

I will leave Muenster to one side for the moment, as it is a much smaller scale operation. Of the two mega- exhibitions, the main pavilions at Venice cleaved most closely to the expected model of setting out an array of the world’s contemporary art, and to offering insightful pathways into it. The facade of the Mussolini moderne Italian Pavilion featured, in giant lettraset, the words “MATTER SO SHAKEN TO ITS CORE TO LEAD TO A CHANGE IN INHERENT FORM,” and “THE EXTENT OF BRINGING ABOUT A CHANGE IN THE DESTINY OF THE MATERIAL,” pasted there by Lawrence Weiner. Despite the curator’s hopes that this array would unambiguously declare that the entire exhibition was inflected by a precise ambiguity, these statements, at once obvious and obtuse, did not bring about the desired affect. Nor was it achieved in the anteroom, which was filled with a May Pole of the macabre by Nancy Spero, or in the approach halls.

No one, however, could miss the message of the central space, dominated by seven paintings by Sigmar Polke, his Axial Age series of 2005-07. The arrangement of the huge works–most 15 feet across, one a triptych– immediately evoked the Rothko Chapel in Houston. So did the violets saturating each silken field, and their extreme sensitivity to changes in natural light. At Houston, the spiritual quest invited by the paintings is not specific to an organized religion or an historical culture. Polke, however, could not avoid inserting images of die wunderjahre, of Friedrichian questing unto Byzantium. Rothko came close, but did not succumb, to the alchemical conceit at work in these Polkes: paint’s poisons holding out the possibility of transformation into gold.

This occurred, with predictable crassness, when luxury-goods magnate Francois Pinault–celebrating his win over the Guggenheim franchise in the recent battle to govern, at a donation of $30 million, the first dedicated contemporary art museum in Venice–bought the series for “many millions.” A relevant sidebar is that his show at the Palazzo Grassi is the disappointment of the season: works by interesting and rarely-seen artists such as David Hammons are shown in depth, but are swamped by the agenda-setting overkill of middling, yet over-exposed artists such as Anselm Reyle and Urs Fischer, and the all-pervasive sense of being in a high-end boutique. Not a good look for the Punta della Dogana.

We know that large-scale statements are inevitable as art institutions continue to compete as sites of attraction within spectacle culture. By installing Polke’s suite as his centerpiece, Storr is simply following the trend in blockbuster exhibition types beyond surveys and themes to the current concentration on one-artist shows that fill large spaces or entire museums. Matthew Barney’s Cremaster series at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 2002 seemed the apex, but it has been matched by, among many others, Richard Serra’s The Matter of Time at the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao (2006) and the first of the Monumenta sequence of exhibitions at the Grand Palais, Paris, which began this May with Anselm Kiefer’s magisterial Sternenfall. (No surprise that Serra is next at the Grand Palais; interesting that Christian Boltanski will follow.)

Yet each of these installations, while spectacular in itself (to the point of grandiosity), responds to the widespread thirst for some kind of clarity within the confusions that obscure all attempts to see the shape of the current world-picture. Each includes elements that expose the limits of excess, and that seek small, sometime human-scale anchors for individuality within it. Serra does this quite literally, in the material force with which his steel slabs govern movement through space; Kiefer profiles on epic scale the ruined structure that Modernity has become while pointing to the persistence of poesis within it; and Barney revels in the media saturation of contemporary life while glamorizing the mock-heroic travails of the individual’s quest through its multifarious obstacles. In contrast, a quite distinct and critically acute take on these issues appears in Paul Chan’s digital projection series The 7 Lights (2005-07), shown in its entirety in the Serpentine Gallery, London, in May 2007. Like Kiefer, Chan evokes the cycle of creation, but does so only to show that, in current conditions, the tropes of destruction–particularly those of the fundamentalisms–are multiplying.

One of the few works at Venice (and certainly the only one at the Giardini) to match Chan’s is Steve McQueen’s Gravesend (2007), a wide-screen video shot at Walikale, in the Congo, the XRF Analysis Laboratories in Nottingham, and at Gravesend, on the Thames near London. What unites these places is that the last is the site conjured by Conrad in his novel Heart of Darkness, as his narrator sets out on his journey, whereas Coltan, a mineral much used in modern electronic equipment, is mined, by hand, in Walikale, and processed in Nottingham. Through carefully chosen steady cams, insistent sound, beautifully lit close-ups and abrupt editing, McQueen evokes the abstract energies that lock these localities to each other: a globalizing scenario that, after these quasi-documentary sequences, he manifests in a flow of blackness that splits the glowing white screen like an oil spill across sand.

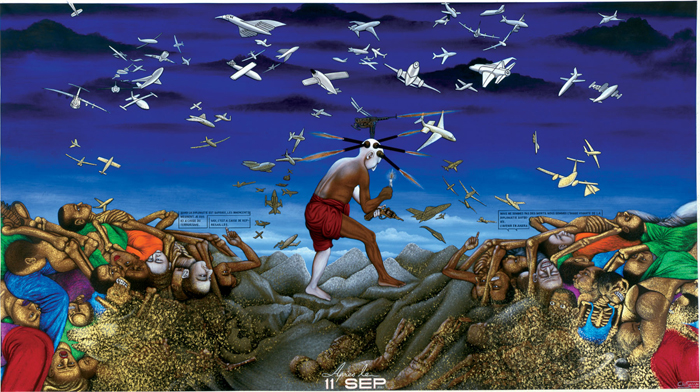

Chéri Samba, Après le 11 Septembre, 2001, 2002. Acrylic and glitter on canvas, 200 x 350 cm. Photo: Patrick Gries. Courtesy C.A.A.C.—The Pigozzi Collection, Geneva. © Chéri Samba.

Compared to this enlivening of artistic abstraction, the rooms of elegant paintings by Richter, Ryman, Murray and Rothenberg look same-old, while those by younger painters such as Raul de Keyser simply pale into insignificance. A more interesting question is what does the McQueen do to our approach to works such as those of Cheri Samba, a leading artist in the group of self-named “Popular Painters” from Kinshasa? Along with Bodo and Cheri Cherin, Samba occupies a room in the recent rehanging of the Tate Modern collection. At Venice, in the rooms near the painters just named, he shows two large contemporary history paintings: Les Tours de Babel dans le monde (1998), which depicted Africa as the victim of conflicts originating elsewhere, and Apres le 11 Septembre 2001. Painted between May and September of 2002, the latter offered a complex symbolic cluster concerning the roots and effects of terrorism, in a manner recalling Diego Rivera’s destroyed Rockefeller Center mural. The Kinshasa painters continue to advance from their populist starting point, learning fresh ways of conveying their growing awareness of the complexities in which they are embedded. So does McQueen, coming from a different, but parallel and, at times, convergent set of sources. In current circum- stances, not least in Africa, this is what we might most expect: contemporaneous non-contemporaneity.

This is not what we find in the “African Pavilion,” a controversial compromise squeezed into a distant shed in the Arsenale (between even more token Turkish and Chinese presences). Controversy swirled around Storr’s decision–quite late in the game–to ignore already well-developed initiatives to introduce an African presence into the 2009 Biennale, to drop his own thoughts of selecting a few artists for inclusion into his sections (although two huge wall-hangings in the Arsenale by Ghanaian bricoleur El Anatsui dazzle in the visual richness achieved by sewing together such lowly, discarded materials as bottle tops) and put out an open call for proposals for “an exhibition of contemporary art from Africa and the African diaspora.” A slice from a private collection in Angola was selected. While it contains some interesting works, it profiles a taste formed in the 1990s, a patina that spreads to even the recent inclusions. The mostly domestic scale of the works leaves them cowering against the mega- exhibition specials that precede them. Despite drawing on the conceptual skills of curator Simon Njami–a key figure in the largely successful exhibition Africa Remix, which toured extensively between 2004 and 2007 from Duesseldorf to Johannesburg–the outcome is an object lesson in how not to deal with this issue.

If the main pavilion at the Giardini sagged under the weight of the conventionality at its core, the long string of rooms at the Arsenale is filled with–for the most part–overt, declarative statements about current political conflicts. After an introductory installation by Luca Buvoli that, in history museum-cum-funhouse style, recreates the slogans and typologies of Italian Futurism, we step into a reminder of past and present struggles in Latin America with a display of Leon Ferrari’s iconic works from the 1960s (a crucified Christ strung up on a US fighter plane), his 1980s prints of people trapped in maze-like cities, and some of his recent, Ernst-like collages. Opposite, Charles Gaines’ Airplanecrash Clock is a model modernist city through which a passenger plane mounted on an ungainly pole chugs every few minutes, and then crashes. The a-ha! is that this work was made in 1997. This amusing if unexceptional end-of- Modernity allegory looks, after the 9/11 connection has been made, the same.

Óscar Muñoz, Proyecto para un Memorial, 2003-2005. Five channel video-projections, without sound. 200 cm. x 250 cm. Courtesy Galería Alcuadrado, Bogotá, Colombia.

Back and forward, from one side to another, artists bat the crises of our time. Many do so with subtlety and restraint. After the Israeli invasion of Lebanon last year, Gabriele Basilico revisits photographs he took of the destruction of Beirut in 1991. Oscar Munoz paints deft portraits–in water, onto a pavement, in the midday sun–of those who “disappeared” during the incessant warring within Colombia (Proyecto para un Memorial, 2003-05). Adel Abdessemed’s Wall Drawings (2006) are nine perfect circles delineated in highly tensioned barbed wire. This tendency reaches its apogee in a key installation by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, Manas (Utopian City) (2007), in which eight model cities, gathered around a void, evoke both the utopian architecture of the Revolutionary period in Russia and ideal city types from throughout history (including one that enables time to flow up and down, and then stop). Above them, their replicas float, hinting at a Tibetan myth about heavenly replication of the earthly, including its aspirations towards transcendence.

Many other inclusions, in contrast, make their points with one-idea directness. Emily Prince is building a wall map of the United States by making drawings of the soldiers killed in Iraq (with color variations according to ethnicity) and pinning them up according to the location of their hometowns. Paolo Canevari’s video Bouncing Skull (2007) tracks a young man amid the ruins of Sarajevo showing off his soccer skills by obsessively kicking and fetching a rubberized skull. Hiroharu Mori’s A Camouflaged Question in the Air is quite literally that: a white balloon with a question mark in Warhol-style camouflage on it. Made in 2003. Why resurrect it? Sometimes these simplicities are the result of a bout of curatorial correctness. Thus Riyas Komu’s sequence of painted portraits of the conflicted face of a Palestinian suicide bomber is hung next to series of photographs by Tomer Ganihar of wounded dummies used in Israeli hospitals to teach treatment techniques. Opposite, one of Rosemary Laing’s studies of detention camps in the desert is entitled Welcome to Australia (2004).

Rosemary Laing, Welcome to Australia, 2004. From the photographic series, To walk on a sea of salt. Courtesy the artist and Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne.

While Storr defied expectations by including so much overtly political work, he retreated to more familiar instincts by consciously interrupting this discourse with works that made their points poetically–indeed, cried out for attention to the uniqueness, even eccentricity, of their vision–and did so by performing their anxieties as a problem for a medium. Kim Jones, Andrei Monastryski, Felix Gamelin, Valie Export, Francis Alyes all did this, with varying success. In a similar gesture, a set of dark rooms in which one may view Yang Fudong’s films of the interminable wanderings of seven Chinese intellectuals is strung like an anti-vertebra throughout the space.

Ignasi Aballí, Llistats (Morts I), 1997-2003. Digital print on photographic paper. 150 x 105 cm. Courtesy Elba Benítez Gallery, Madrid.

The last rooms attempt to weave these conflicted currents together into an open-ended conclusion. Rainer Ganahl Googled “the politics of education” and found a list of seminars, conferences, and lectures, which he reproduces in lettraset. On either side he displays his photographs of such events, from the artist Allan Sekula teaching photography at CalArts to the late Pierre Bourdieu on a panel in Paris. Manon de Boer flew to Sao Paulo to interview theorist Suely Rolnik. His travelogue is shown with rather mannered aphasic freeze-framing, yet the depth of Rolnik’s thought about the subjective states of postcoloniality comes through. Since 1997, Ignasi Aballi has been cutting out from the print media headlines that pair an identifactory category–such as “Islamists,” “disappeared,” “workers,” “murders,” or “victims”–with a number. This decontextualizing, and reshaping into lists, draws us to imagine worlds of connection of the kind that used to be traced by Mark Lombardi, for example. Three photographic collages by Lyle Ashton Harris, arranged to create a space for memory and reflection, showed a generalized African/ Latin American dictator, his bourgeois supporters, and a victim dying (presumably) of AIDS. This is less affecting than Alalli’s lists, largely because its placement rather heavy-handedly attempts to jerk us away from reflection on our own processing of the themes of the exhibition, and back to “reality.”

Charles Gaines, Airplanecrash Clock, 1997/2007. Mixed media, electronics; 9 x 13 x 5 feet. Installation view at Venice Biennale, 2007. Photos: Sergio Martucci. Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

The final work lets us out again, back into approved contemporary art’s patent ambiguities. Philippe Parreno treats us to an update of Andy Warhol’s famous 1964 exhibition of helium-filled silver balloons. This time round they are black, shaped like the “speech balloons” in comic books, and stay resolutely stuck to the ceiling. Into a wall next to the exit is set a small screen. A favorite of eighteenth century automata, the Writing Boy, is shown inscribing, with the laborious movements that had earlier crashed the plane in Gaines’ Airplanecrash Clock, this question: “What do you believe?” And then this answer: “What you see?”

What of Venice outside the main exhibition? Citing the impacts of globalization, but emphasizing works that displayed those impacts, the 2006 Sao Paulo Biennale abandoned its emphasis on distinctive national representation, leaving Venice as the only one that persists with this model. How does it look there? Anachronism is the Biennale’s root condition; it has always (well, for most of its history since the 1930s) traded on the disarming mismatch of presenting the most contemporary art in settings redolent with elegant decay. (An exchange exquisitely portrayed in the staging of the Artempo exhibition at the Palazzo Fortuny–for all its unabashed aestheticism, this compilation of eccentricity and erudition is yet another kind of exhibition- as-argument, and alone would justify a visit to Venice.) But the national pavilions continue to struggle for impact and relevance. Part of the problem is that, given the proclivity towards installation as a mode, their size permits the showing of work by one or at most two artists. Two challenges then arise.

First is choosing a project or projects that match the pavilion. Rare successes this year included Aernout Mik, who rebuilt the Dutch Pavilion, turning it into a de facto training camp for the processing of illegal immigrants; David Altmejd, who filled the awkward Canadian pavilion with a natural-history-museum-style display of figurines that parodied national wilderness myths; and Minika Sosnowska, whose fractured steel frame cowering within the space accorded Poland seemed a poignant metaphor of institutional failure. Among the more interesting multiple representations were Spain (for showcasing the smart satirists Los Torreznos) and Russia (featuring an amazing apocalyptic animation by ASE+F).

Callum Morton, Valhalla, 2007. Steel, polystyrene, epoxy resin, silicon, marble, glass, wood, acrylic paint, lights, sound, motor; 465 x 1475 x 850 cm. Palazzo Zenobio, Venice Biennale 2007. Courtesy of the artist, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney and Snna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne.

Second problem: How representative are one or two artists? Many countries opted to show one artist in the Giardini and others elsewhere in the city. A good decision for Australia, as it made available both Susan Norrie’s powerful set of videos HAVOC (2007), showing the social impacts on an Indonesian village of a devastating flood of hot mud, and Callum Morton’s three-quarter scale rendering of the ruined remains of his architect father’s modernist dream home. Architecture in the aftermath, absolutely. And for Britain, the am-I-gauche, please swallow my trivia unaesthetic of Tracey Emin evaporated when set against the emotional precision of the videos of Willie Doherty and Gerald Byrnes. If we add to their recent output that of James Coleman (his Retake with Evidence, a feature-length film tracking Harvey Keitel in full Orestia mode, is arguably the master work at Documenta 12), we are blessed with a concentration of cultural achievement that matches that of the great Irish playwrights and poets of the early twentieth century. Not all external sites are so successful (although Thomas Demand at the Fondazione Cini comes close), yet the big plus for visitors is the experience of getting into at least parts of sixty of Venice’s enchanted palaces–and doing so without the commercialism that tainted some earlier Aperto offerings.

Retake with Evidence, 2007. © James Coleman. Performed by Harvey Keitel. Projected film. Courtesy: James Coleman; Marian Goodman Gallery; Simon Lee Gallery; Galerie Micheline Szwajcer.

If the 52nd Venice Biennale was curated like a rough outline of two chapters in a textbook on contemporary art, including sidebars and footnotes, squeezed into a museum-like sequencing of galleries, Documenta 12 felt like an essay for a specialist art journal in which two art historians ruminate together about what they see as an unjustly neglected current in art since the 1960s, how it might make us rethink the standard story of late Modernism, and how it might have touched other, more recent developments. The current is the first stirrings of feminism among artists, particularly women artists, as expressed on both domestic and public scales, through alternative performance of gendered roles and through rethinking the symbolic values of ordinary materials. Not your usual mega-exhibition fare, nor the typical apparently invisible yet actually authoritative curatorial style. A bold step, then, into a lower key. How does it play out, conceptually, and on the ground, in the actual spaces?

Edited by Georg Schoellhammer, Documenta Magazine No. 1, 2007, Modernity? poses the first of the exhibition’s guiding questions: Is modernity our antiquity? A riveting query, it was first raised in a way that is still relevant to us by Charles Baudelaire in his famous 1863 essay “The Painter of Modern Life,” and has been asked, in different ways, by the greatest thinkers about how art relates to modern life, notably Walter Benjamin, Marshall Berman and T.J.Clark. Writing inside the eye of the transition, Baudelaire was enthralled by the very idea that art, responding to the demands of modern life, commits itself to the unknowns of “the transitory, the ephemeral, the contingent,” so that it can become, one day, what the classical tradition had always claimed to be, and now, suddenly, no longer could be–that is, “eternal and immutable.” Imagine not the absorption of the new into tradition, but a distinctively modern eternality, forged in the crucible of the contemporary! Wandering those same, but in the 1930s so different, Parisian streets and arcades, Benjamin saw that rampant industrial and consumerist capitalism, the eruptions of which so excited Baudelaire, was, along with seductive phantasmagoria, steadily creating its own material ruins. Against this grain, and with the Robert Moses versus Jane Jacobs battles for downtown Manhattan and the Bronx during the 1960s foremost in his mind, Berman, in All That Is Solid, insisted on the positive productivity of Modernism. At the turn of the last century, in his Farewell to an Idea, T.J. Clark profiled the decline into stagnation of the modernist ideal that the arts and social transformation could advance together to the benefit, in principle at least, of all.

Artist Mark Lewis, in a brilliant essay in Modernity?, charts this historiography, showing that its answer to the question is yes. Modernity has become, for us, something like antiquity was for the first modernists. Unlike their situation, however, there is little to look forward to. Indeed, utopian thinking of nearly all kinds seems to be evaporating. Nevertheless, Modernity, however flawed, is all that we have, all that we may ever have. It is our contemporaneity. Artists, including Lewis (and others such as Tacita Dean, Susan Hillier, Mark Dion, the Wilson sisters and Liam Gillick, just to name some British artists), are drawn to meditation on this melancholy situation. Modernity, and how its pastness is stultifying the present, is the most pressing concern of art that would be contemporary. To me, this view of our present, however internally subtle it may be (and it is), is at best a partial truth, and at worst negatively one-dimensional.

In such a context, ambitious, independent art historians are naturally drawn to the moment when this change of heart began to occur: the 1950s and 1960s. And to places where its occurrence is less chronicled than at Black Mountain College and the downtown galleries in Manhattan–Japan, Brazil, and the “Eastern Bloc” countries, as they were then known. As well, they begin to see that the grand narrative of Modernism’s progress through various Parisian-based avant-gardes, with occasional peripheral offshoots (Moscow, Rome, Amsterdam, Berlin), followed by the migration to New York, is a narrow, exclusionary narrative. It ignores the creation of “alternative modernities” at art centers all over the world. This postcolonial, revisionist revival– currently led by prescient art historians such as Kobena Mercer (who favors “cosmopolitan modernisms”)–is gradually outflanking the Adornoesque negativity just mentioned. It is being applied not only to what were previously regarded as cultural peripheries, but also to previously ignored artists working at the well-known centers. It is the guiding spirit of Documenta 12.

How, then, to pursue this (to me entirely) laudable objective in the spaces available at Kassel? What kind of experience does its pursuit afford the visitor?

Hanging in the stairwell of the Fridericianum, as a kind of tutelary image, is a copy of Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, the modest watercolor of 1920 that Walter Benjamin inspiringly misread as representing the Angel of History looking backwards, in horror, at the detritus and destruction that Modernity was depositing before it. But the big questions about Modernity are not tackled in a big way. No large statements, no grandeur of scale. Nothing by the museum–and market-endorsed contemporary art stars–with the exception of a tiny 1977 Gerhard Richter painting based on his photograph of his young daughter, her angled head staring out as if awaiting execution.

In this arcane fashion, abruptly, in a side room, appears the exhibition’s second theme. The idea of “bare life” has been acutely articulated by Giorgio Agamben as the irreducible otherness of each of us, to ourselves, to those closest to us, and to our social systems (especially when manifest in those places, such as refugee and interment camps, that governments are more and more seeking to place beyond not only the law but justice). This gesture is typical of how the curators stage their ruminations: as hints and allusions, hypotheses that are then qualified, leaving suggestions in their wake. Nevertheless, a pattern of thought gradually emerges, one that is played out, in different registers, at each of the five main venues: the Museum Fridericianum, the Neue Galerie, the documenta-Halle, the Schloss Wilhelmshoehe and a temporary structure, die Aue-Pavilion, in the meadow (aue) adjacent to the Orangerie.

During the 1960s and 1970s, “The personal is political” was a key slogan for second-wave feminism in the West. The curators know that this idea had other resonances in Eastern and Central Europe under the Soviet system, and South America during the time of the dictators. And that, sufficiently nuanced, it has much to offer the present, especially to artists seeking to give form to the challenges of what it is to live in the accelerating complexities of the contemporary. This is at the core of their enterprise, the gamble for which they have transformed what have become the protocols of the mega-exhibition.

In many parts of the exhibition, extraordinary instances of personal witnessing, many of them known only to historians of their region, may be found. I did not know of Lotty Rosenfeld’s painting, in 1979, of a disruptive sequence of white lines on the roads of a closely guarded area of Santiago, Chile, then occupied by the military regime. Nor the work of Polish pair Zofia Kulik and Przemyslaw Kweik who, in 1972, formed the duo Kweikulik in order to pursue actions based around semiotic exploration within everyday life–and, for two years, included their newborn son in many of them. This parallels in some ways the enterprise of Mary Kelly’s famous Post-Partum Document (1973-79), a systematic yet Lacanian documentation of her son’s language acquisition, which, although not included here, is one of the exhibition’s presiding geniuses. Indeed, artist after artist is shown making works within the frameworks of domestic settings. Shifts in the mother-child relationship as patriarchy crumbles before feminism is a major subtext, as is the revaluation by women of their status as artists. Jo Spence shows her transformation from being a subject of photography to an active photographer –devoted, sadly, to recording her struggles against breast cancer. Kelly includes a new work, Love Songs (2005), chronicling the history of subjectivity within feminist discourse.

Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, Remodelling Photo History, 1982. Black & white photographs on red plastic panels. © Jo Spence and Terry Dennett.

The impact of this personal/political convergence on artists’ materials and working procedures–a “migration of form” that the curators correctly see as spreading, rhizome-like, between peripheries–is another, closely related theme. It is illustrated in detail by Luis Jacob’s string of collages Album III (2004), but has deeper roots. During the 1960s, Brazilian artist Mira Schendel clustered wool and twines into surrogate body- shapes and drew delicate concrete poems. Venezuelan artist Gego created her Reticularea, matrixes of hooked wires. While the latter are absent from Kassel, small works by Schendel are shown, as are many by lesser know artists working with found materials. The South American flowering of this aesthetic culminates in a major retro-Concretist sculptural installation by Iole de Freitas that literally grows from inside the first floor of the Fridericianum to flourish on its exterior. For all its differences in inheritance, materiality and gendered address, her recent work matches that of Richard Serra. The still center of Documenta 12’s main themes may be found in the print room of the museum at the Schloss Wilhelmshoehe. A Qing Dynasty lacquer-work panel of domestic objects, an anonymous Indian miniature from 1813 of a woman spinning, a minimalist woodblock of 1835 by Hokusai are shown near, among other delicacies, an exquisite lettraset notebook by Schendel and a delicate drawing from the 1980s by Nasreen Mohamedi, the Indian artist whose work was a standout at the 5th Asia-Pacific Triennale in Brisbane last year and continues to be so here. (Geeta Kapur’s chapter in her 2000 book, When Was Modernism, was a revelation.) The room of Mohamedi’s work at the Neue Galerie, juxtaposed to a large painting by Agnes Martin, is a space to be savored, not least for the glimpse that we are given, through the display of pages of her diary, of the compacted, obsessive yet serene vision that drove her work.

Iole De Frietas, Untitled, 2007. © Iole De Freitas. Courtesy Laura Marsiaj Arte Contemporanea, Rio de Janeiro; Gabinete de Arte Raquel Arnaud, São Paulo. Photo: Margherita Spilutini.

Less successful was the device of choosing a half- dozen artists with strong regional reputations–John McCracken, Charlotte Posenenske, Gerald Rockenschaub, Juan Davila and Kerry James Marshall–and using their works as “hinges” (turning points that, due to their internal complexities, could swing the flow of meaning both ways–in Posenenske’s case, quite literally). Although I enjoyed the experience of hearing a docent explain, to a German-speaking group, every detail of the iconography of one of Davila’s multi-layered, Australian- Chilean anti-allegories, few of the chosen artists have the depth to carry such a load.

This was cruelly exposed in McCracken’s case. Located, alone, in the center of the entrance foyer of the Fridericianum, his mirror-sided, gold hued column Swift (2007) is the first work seen by the majority of visitors. Yet it is positioned in a space itself covered in mirrors, and thus filled with spectators gawping at themselves multiplied. Yoyoi Kasuma without the models or the dots; James Lee Byars without the fetishism. Instantly, it becomes a space where art vanishes into a parody of “pure form” (the so-called transmigration of which is one of the curators’ less propitious fascinations) and the dazzle of distracted, narcissistic spectatorship. Worse still, McCracken’s brief and artistically clumsy flirtation with Tantric imagery in 1971 appears throughout the exhibition, often matched with Persian carpets that manage these patterns so much better but seem included only because of the Californian artist’s brief dalliance. When his better-known, and highly competent, “plank” sculptures turn up, they are themselves parodied or outshone (presumably unintentionally) by other artists. In the Aue-Pavilion, Rockenschaub turns one into a green inflatable, while at the Neue Galerie, a forlorn plank leans against one wall, while opposite is hung Andrea Geyer’s Spiral Lands (2007), a riveting sequence of photographs and texts relating to the idea of “justice as indigenism.” Finally, in the print room of the Wilhelmshoehe, a set of McCracken’s drawings for sculptures is shown. Unfortunately, they include admonitions to himself, such as “The important thing is the bigness of the statement.” Will McCracken’s reputation ever recover from this loving treatment?

A fourth theme, one shared with Venice, is the emergence of the postcolonial, and the vicissitudes of globalization. Central to the previous Documenta, these issues seem a disruption to the “alternative modernities” current at the core of this exhibition–mainly because, as we have seen, that kind of art historical revisionism is most deftly carried out by these curators when exemplified by artists from the European peripheries, the U.S., and, to a lesser but still significant extent, South America. Africa appears in the Aue-Pavilion soon after one enters, in the form of a wall by Bill Kouelany that cuts across most of the space. Made in 2006-2007 from cloth and papier-mache stitched in brick-like fashion, yet crumbling at either end and broken by silhouettes of headless soldiers, it is also punctuated by videos featuring the artist, who is from Brazzaville, Congo, raging against the effects of the civil war that recently consumed her country. It’s a porous barrier, then, as fragile as those who erected it. Behind it a delta of African material: Guy Tillim’s Congo Democratic, beautiful photographs of moments during the 2006 elections; Romauld Hazoume’s engaging water carrier sculptures (some constituting Picassoid masks, others a huge boat entitled Dreams–regrettably shown with a paradise beach backdrop and a line of poetry); and Dierk Schmidt’s installation The Division of the Earth (2006-07), a sequence of elegant abstract paintings that explore, with precision, the spatial logics in play at the 1884-85 Berlin conference at which the European powers decided who would share which spoils out of Africa.

Allan Sekula, Installation view, Documenta 12. Courtesy the artist; Galerie Michel Rein, Paris; Christopher Grimes Gallery, Santa Monica. © Allan Sekula. Photo: Frank Schinski /Documenta Gmbh.

These kinds of questions play themselves out in, among others, Lu Hao’s scrolls of the modernization of Chang’an Street, a major thoroughfare cutting through Beijing; in Leon Ferrari’s maze prints; and in Simryn Gill’s plant and animal matter casts of the machine parts of a 1984 Tata truck that once plied the jungle trails of Malaysia. They appear at other venues, not least in Allan Sekula’s large photomurals, which take on the most prominent tourist sites in Kassel, including the Wilhelmshoehe Station, with an anti-G8 summit poster proclaiming “Alle mensch werden schwestern” (“All will become sisters”), and below the egregious monumental theatre to the Labors of Hercules in the gardens of the Schloss, where they remind viewers, with photographs of local workers, of two basic forms of labor: childcare and grave-digging. The last room at the Aue-Pavilion shows what is perhaps the outstanding treatment of this subject in art today, Zoe Leonard’s Analogue project. Since 1998, in a series of frontal, closely-framed, analogue photographs of storefronts and storage areas, largely devoid of people (except for her occasional reflection), Leonard has dispassionately tracked the decline of small businesses in her native Brooklyn and the rise of small businesses in Africa that recycle, as modern, the cast-off clothing of the West.

Works such as this reinforce the curators’ conception of the fecundity and the continuing relevance of 1960s feminist art. Leonard’s career is a striking example of how the questions raised then about wider social issues–and some of the artistic techniques used for addressing them (here, Martha Rosler’s photo and text work, The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems (1974), is paradigmatic) –can serve as a foundation for tackling the even more complex and dispersed problems facing the present. These occur not only within the labyrinths of globalized exchange, but also in intensely personal settings. Imogen Stidworthy’s video installation I Hate (2007) shows the efforts of photographer Edward Woodman, who lost his speech in an accident in 2001, to pronounce words and sentence fragments. Alongside, she exhibits his panoramic photographs of the recent building of the Eurostar Terminal at Kings Cross, drawing out the parallels between such painstaking constructions of verbal and visual languages.

The last, large question posed by Documenta 12–What is to be done?–goes largely unanswered for the two-, three- or four-day visitor. It is addressed in the education program, which is spread over the 100 days of the show. It receives rather token treatment in the third of the magazines. Entitled Education, it mostly echoes the mix of reflective essays and short profiles on previously neglected modernist and avant-garde artists that constituted the bulk of the other issues. A statement by the education curators of Documenta concludes the volume. Of necessity, it amounts to a warm invitation to take up the educational offerings on the site. In all, this is hardly an answer to a question made famous by Lenin, and still, but of course quite differently, pressing today.

There is a mood abroad in Europe that these questions are best tackled by revisiting past moments when issues like them were dealt with by previous generations of artists and curators. In Paris this spring, the major historical survey and the major survey of contemporary art both took this form, quite literally. At the Grand Palais, a comprehensive celebration of the Nouvelle Realists was presented, for the most part, as a string of recreations of the exhibitions in which, since the later 1950s, their work appeared. The Centre Pompidou celebrated its thirtieth anniversary with an exhibition Airs de Paris that, paying homage to Duchamp, focused on art that addressed the spaces and spirit of the city. It did so by mixing new works with installations from key earlier exhibitions at the Centre.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Roman de Münster, 2007. Photo: Roman Mensing/SP07.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Roman de Münster, 2007. Photo: Roman Mensing/SP07.

The most interesting element at Muenster was precisely those many works that reflected on the history of the Sculpture Project itself. Dominique Gonzalez- Foerster did this, on a playground level, by filling a small park with miniatures of previous projects. Kids loved it. Scandinavian duo Elmgreen and Dragset presented a stage play in which maquettes of classic works by Barbara Hepworth (with a smoker’s cough), Alberto Giacometti (suffering from depression) and Jeff Koons (wise-cracking all the while) failed, amusingly, to communicate. Michael Asher’s parking of a caravan at various sites around the city is the one work that has been repeated at each of the iterations since 1977. Then, it was the only genuinely mobile work in a show dominated by minimalist monoliths. Now, it is a quaint artifact. The strongest piece is Bruce Nauman’s inverted pyramid: white concrete wedges sunk into the ground beside a university physics building, where its spatial reversal works with implacable effectiveness, especially if you stand at its center and see that its perimeters are at eye-level. This work was proposed in 1977, but rejected then. That its realization now knocks all the other “new” public art out of the ball park tells us heaps about the trouble that this category of practice is in, everywhere.

Elmgreen & Dragset, Drama Queens, 2007. Rendering: SP07.

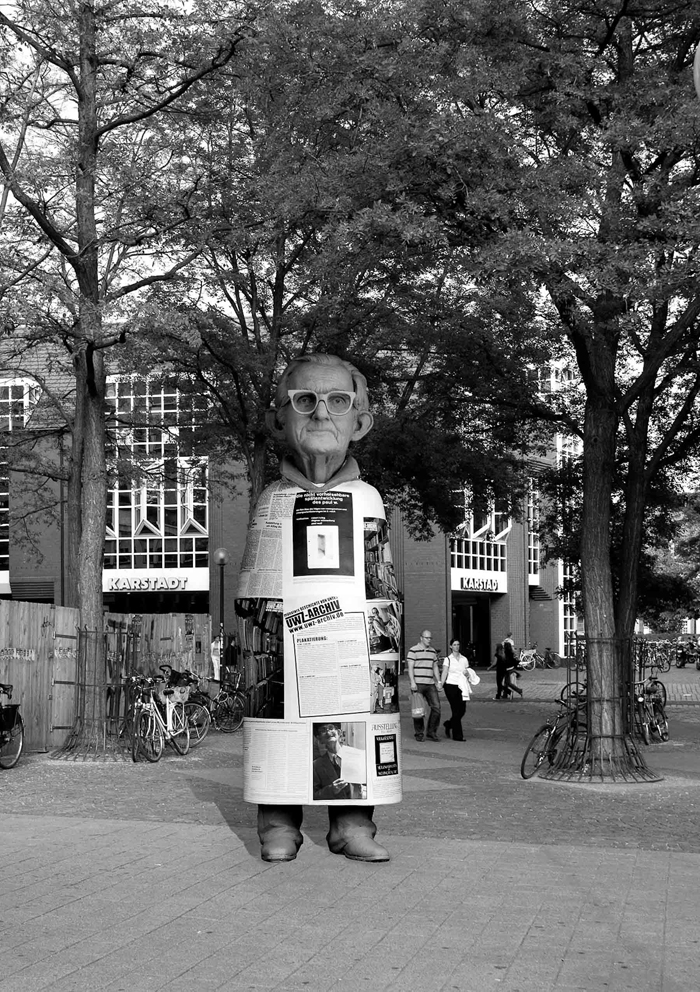

Andreas Siekmann made something close to this point by presenting a pile of junk made of compacted “sculptures”–the brightly colored plastic cows, dinosaurs and mythical figures that pollute shopping malls and town squares all over the world. Perhaps the most resolved piece was Silke Wagner’s The History of Muenster from Below (2007): a civic message pole covered in relevant historical information and topped with a large portrait head of a man who, for many years, stood in just this square calling attention to his ill- treatment as a “mentally disadvantaged” youth when the city was under Nazi control. Wagner’s sculpture proves that local statements about local concerns can succeed as both statements and as art, whereas generalization about locality, as we see so often in Venice and Kassel, mostly fails.

Silke Wagner, Münsters Geschichte von Unten, 2007. Photo: Sarah Bernhard/SP07.

Andreas Siekmann, Trickle Down, 2007. Der Öffentliche Raum Im Zeitalter Seiner Privatisierung. Photo: Roman Mensing/SP07.

We are back to the question with which I went to Europe. In fact, we have never left it. The short answer is this: European cultural institutions, including these exhibitions, seem anxiously aware of how they might look from what they imagine to be the multiple vantage points out there in the rest of the world, yet are increasingly ready to negotiate with these others. At the same time, Europe is, following the 2005 rejection of the proposed constitution, in the aftermath of a definitive moment in its own post-Cold War redefinition. Everyone of conscience senses that these two enterprises are profoundly linked, and is striving to understand how. There are many bleak prognostications, for example, those following “signature events” such as the murder of Theo van Gogh, the threats to Orhan Pamuk and the renewed rage against Salman Rushdie. On the other hand, the recent call by intellectuals such as Timothy Garton Ash and Wim Wenders for a Europe that moves beyond its current economic and bureaucratic forms to (re)discover its “geist” (a secular concept variously translated as “soul” or “spirit”) in a sense of community based on cultural exchange and artistic inventiveness is one sign of a possible shift to a more positive, constructive mood (see Wenders at www.signandsight. com/features/1098.html).

What about the mega-exhibition in these circumstances? Or, more interestingly, what are the challenges facing responsible curatorship at this time? Retrospection–the longer the better–is essential to avoid falling into the narcissistic nowness that historians label “presentism.” But “melancholy modernism,” the insistence that picking one’s way through Modernity’s ruins is the only way to be contemporary while avoiding the superficialities of spectacle culture, runs the opposite risk of emptying the present of all possibility. Returning to the recent origins of contemporary concerns is a necessary step, but staying there would be a mistake. To value only that contemporary art that echoes these earlier issues would be another error–a kind of “pastism.” These are ugly words, for ugly phenomena, however attractive as options these pathways might currently seem. Better to confront–as so many artists, and a few curators, are doing today–the real issue: How might we live now?

Terry Smith, FAHA, CIHA, is Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh. He is also a Visiting Professor in the Faculty of Architecture, University of Sydney. During 2001-2002 he was a Getty Scholar at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, and in 2007-08 is GlaxoSmith- Klein Senior Fellow at the National Humanities Research Centre, Raleigh-Durham, NC. From 1994-2001 he was Power Professor of Contemporary Art and Director of the Power Institute, Foundation for Art and Visual Culture, University of Sydney. He was a member of the Art & Language group (New York) and a founder of Union Media Services (Sydney). He is the author of a number of books, notably Making the Modern: Industry, Art and Design in America (University of Chicago Press, 1993); Transformations in Australian Art, Volume 1, The Nineteenth Century: Landscape, Colony and Nation and Volume 2, The Twentieth Century: Modernism and Aboriginality (Craftsman House, Sydney, 2002); and The Architecture of Aftermath (University of Chicago Press, 2006). See www.terryesmith.net.