On February 25, 2010, Mary Kelly gave what she termed her “lifetime lecture” at the Hammer Museum.1 Kelly is a professor at the University of California, and each faculty member of the department of art presents a public lecture as part of an ongoing series. Kelly reckoned that, given the numbers, it would be “a lifetime” by the time her turn came around again. And so she used her turn to talk about her work as a body of work: an artist’s statement of the big-picture variety. But as Kelly spoke, it occurred to me that what I was watching was not a faculty presentation, or public lecture, or artist’s statement-even one writ large-but rather a performance of a performance of an artist’s statement, one that engaged the apparatus of auditorium, audience, museum, oeuvre, slide show, microphone, lighting (bright and dimmed), and full-time tenured faculty position to form a tensile engagement with temporality, narrativity, and the particularly plastic form of attention the public grants its more iconic members. And in this, the body of the work became the body of the artist, and, as discourse would have it, vice versathe artist being finally the work of the work itself.2

Kelly divided her talk into a detailed discussion of several major pieces, beginning with a close read of her now-fundamental Post-Partum Document (1973-1979) through to her Flashing Nipple Happening, Documenta XII (2007), a reworking of her Flashing Nipple Remix (2005), including, inter alia, Interim (1984-1989), Gloria Patri (1992), Circa 1968 (2004), and Multi-Story House (2007). Although her exegesis of each was an admirable exercise in concision and amplification, it was the broader remark that resounded. For, while Kelly described her work as “project based,” what emerged from her talk was a projet-a plan, an outline, something necessarily involving labor and premeditation. There was the primary labor of the birth of a consciousness alongside the birth of a specifically female consciousness, and there was the one (not one) that is always aware of labor as (gendered) consciousness, and, throughout, there was a studied consciousness of labor as language in the sense of the structuring exchange. I am because of the currency of me, vis-a-vis.

All works by Mary Kelly. Courtesy of the artist and Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

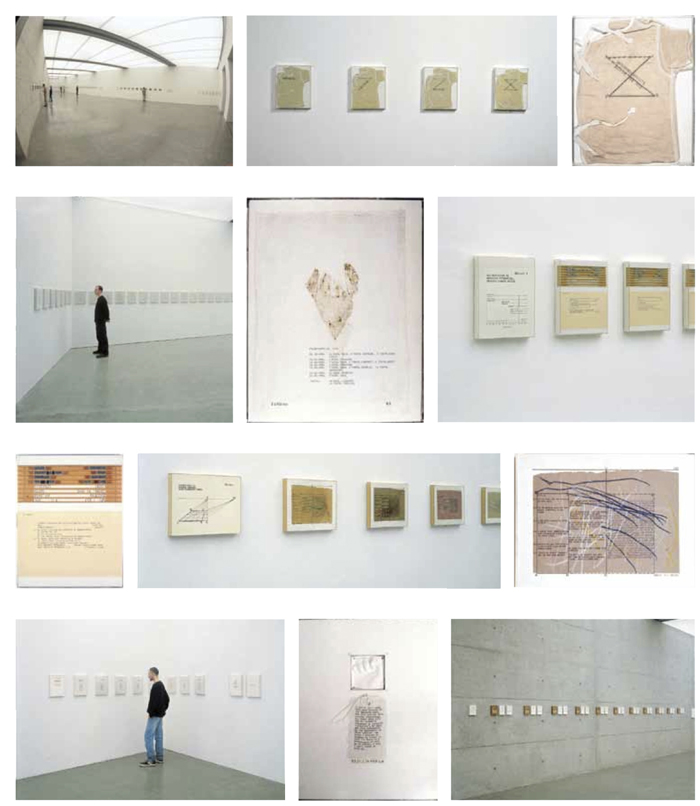

Taking these precepts in the order presented in the lecture, Post-Partum Document (1973-1979), is an installation in six installments. Each installment is a combination of documentation and design: physical objects, such as fecal-stained diaper liners and scraps of baby’s comforter, act as proof of developmental stages, such as weaning and the transitional object. These small body-objects are combined with large thought-objects, such as graphs, grids, and diagrams. Ultimately, body and mind come together in the final installment, in the form of the segregate self of the child who signs his own name (a signature set in stone).3 Born of Lacanian psychoanalysis; 1970s British, collectivist feminism, and 1970s conceptual art practices,4Post-Partum Document served to critique each by way of the other. Moving from the direct orality of nursing and weaning to the sublimated orality of speech and writing, Post-Partum Document famously chronicled the emergence of the consciousness of the child as subject as well as the consciousness of the mother as Mother.5 Post-Partum Document provided proof of a specifically “female fetishism (the various substitutes in which the mother invests in order to disavow separation from the child).”6And thus the Mother is shown as Mother, barred that is, in the Lacanian sense of systemic or constitutional incompleteness: the thing that will always-must always- separate the signifier from the signified. It occurred to me while listening to Kelly thatonce the child acquires the ability to sign his (mother’s) name, language serves not only as the child’s introduction to the symbolic order and the mother’s castration, as explicated by Kelly herself,7 but also as the mother’s re-instantiation as signatory of that order-the “thing” that throws order itself into being.8 In other words, “thou art thy mother’s glass and she in thee.”9 The labor of the child is to come into language, i.e., to come into being. And the labor of the mother is not the birth of the child, but the birth of herself as one who bears another into being. Put another way: the labor of the child is language; the labor of the mother is image.

All works by Mary Kelly. Courtesy of the artist and Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

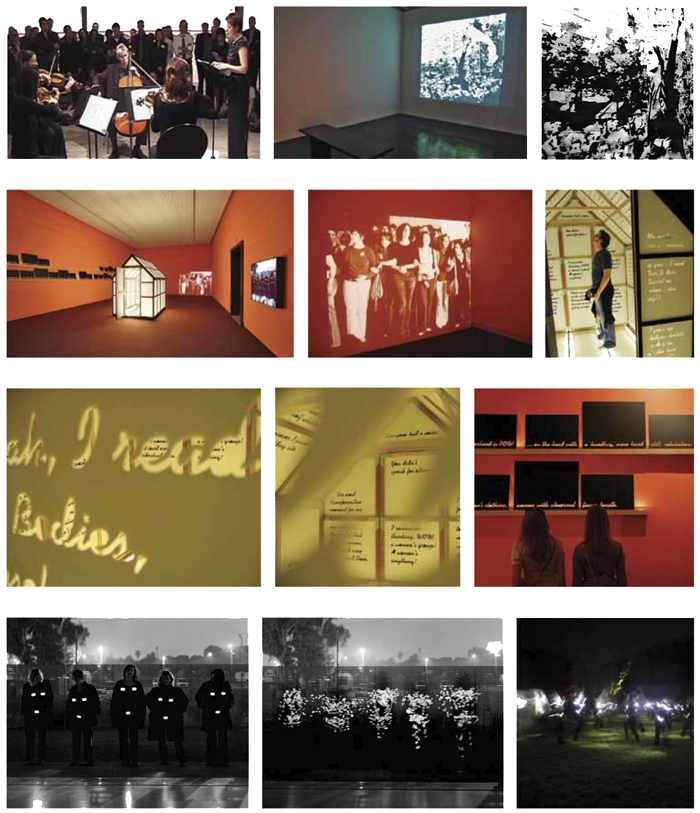

Like the several selves it is to serve, female consciousness is revealed by Kelly as necessarily multiple, necessarily lingual. This was most directly represented in Kelly’s lecture by Multi-Story House (with Ray Barrie, 2007), a greenhouse structure where various statements made by younger women (“My mother was a feminist”) appear on exterior walls while statements made by the preceding generation are inscribed inside (“Everyone had a voice”). Though one may enter the structure to see the interior script, one may also look through the clear cursive writing on the otherwise opaque acrylic panels. Elegance, I thought, disguised as simplicity. Again, the materiality of language (the hand in the handwriting) betrays its signification: while the statements appear plain and to their points, the clouded space around them forces the reader/viewer to literally see through each, turning each reading/viewing into not just an encounter with history or ancestry, but with the transparency of subjectivity and the necessary constriction of perspective that Erwin Panofsky noted was (symbolically) required for a stable point of view. Within dynamism, stasis. Within language, image. With one, always another.

In the beginning of Jacques Lacan’s seminar on the concept of analysis, Mme. Aubry says that while she understands that hate lies at the conjunction of the imaginary and the real, “what I don’t understand quite so well is finding love at the conjunction of the symbolic and the imaginary.”10 Lacan responds by invoking “the structuration of speech in search of truth on the model of those allegorical paintings which proliferated in the romantic era, like virtue pursing crime, aided by remorse.“11And allegory is everywhere in Kelly’s work, although it’s not truth she’s after but the structuring search itself.12 For, as I have written elsewhere, it is allegory that animates conceptualism: not the cogent injunction referenced by Lacan in his seminar, nor the shattered narrative adored by Benjamin, who knew that ruins are better than castles, but the allegory of the narrative impulse, that which churns consciousness in all its forms, including the ostensibly eschewed.13 For the allegory manifest in conceptualism is the allegory of the allegory: “The search of truth” is the profound and trivial desire for sense-making, for schemas of relationships between things, for causes and effects, call and response, in this order. What the best conceptual work does is refuse to prescribe specific content to the concept as container. The point is not to answer the question what is the work about, but to question the work as another question. As much as Kelly interrogates the feminine, in all its fabricated forms, her interrogation is more fundamentally about interrogation; at the real risk of de minimis collapse, Kelly repeatedly asks the famous Lacanian question che vuoi (“What do you want?”). But hers is a question marked by its hook: Just as Lacan posited Oedipus as the effect, not the cause of symbolic castration, Kelly’s work returns again and again to the question of the question- What’s it to you? Meaning, what’s it to?

All works by Mary Kelly. Courtesy of the artist and Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

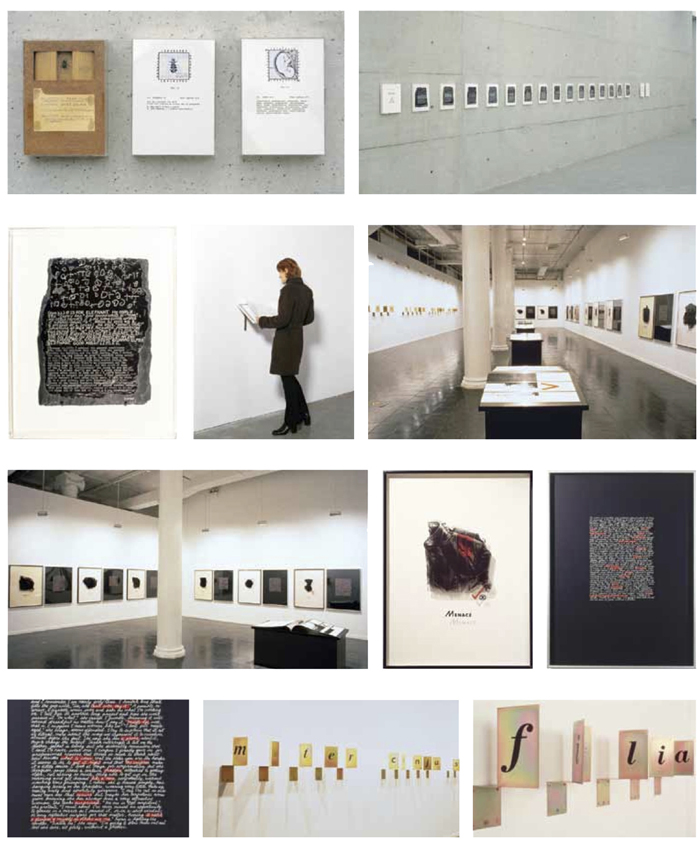

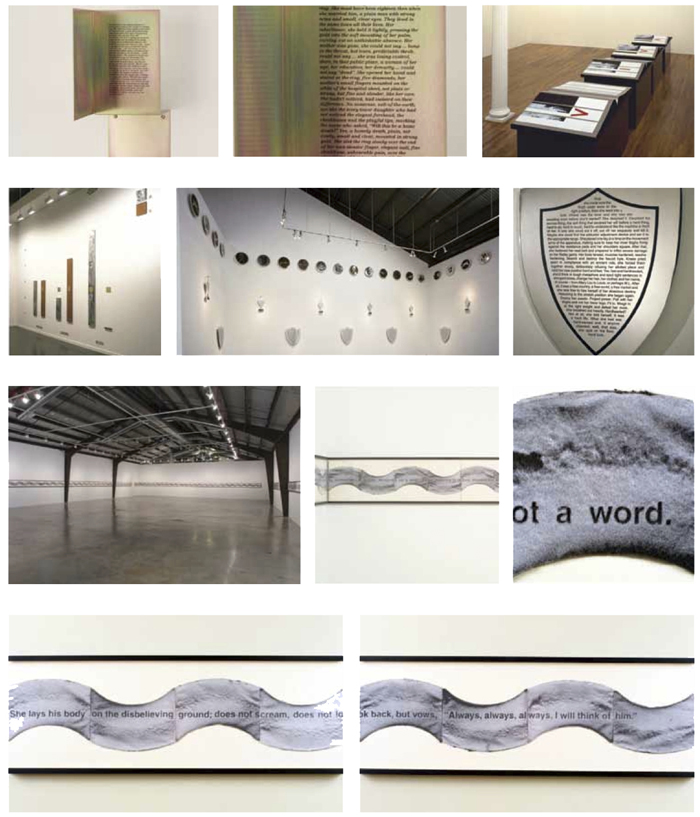

But I’ve jumped ahead. In real time and in lecture-time, Multi-Story House (2007) followed Interim (1984-1989), an exhibition containing thirty panels set in triptychs, arranged in four parts, each part a part of feminist discourse (Corpus, Pecunia, Historia, Potestas).14 In her Hammer discussion, Kelly confirmed that Interim gives the question mark precedence, noting that she has always believed in the absolute right to speak, contingent upon the speech being an interrogation. Parveen Adams has written about the act of interpretation and transference love in Interim and “the question” as the pivot-point of discourse between work and viewer.15 In her 1991 essay, Adams concluded that Kelly had succeeded in Interim in emptying out the object for the subject of the viewer: in short, succeeded in performing the discursive role of the analyst in clearing a space that the subject may fill with its own desire. But I didn’t see Interim at the Hammer—I saw Mary Kelly and a series of images of Interim, a discourse enveloping another discourse about discourse, the thing around the thing being talked about which, like the object of desire, is put in front of us as a point of attention, not as a means of resolution. So I saw a story of making. And in this story of making, Kelly returned by way of the prepositional caption (the “what’s it to“) to something Adams touched on in 1991: the ekphratic moment.16 Adams compared Kelly’s refusal to supply the viewer with answers to Virgil’s description of Aeneas weeping upon seeing a wall frieze of the Trojan War. For Adams, the significance of this ekphratic moment is “in” Aeneas “as subject of the signifier…There is a subject supposed to know and there is signification.”17 But two additional points need to be made. First, Aeneas appears to misread the wall-classical ekphrasis was notoriously about point of view and the subjective imperative-i.e., part of the work of the narrative pause in epic poetry was to show that the subject didn’t know.18 Second, the representation of representation is fundamental to any written representation of the subject. The mother markers of Post-Partum Document become, in their retelling, less fetish objects than icons of a kind of cultural performance. In that case, they act as icons attesting to an iconic and (now) i-canonical (figurally unrepresented / linguistically re-presented) female body. And in the Hammer, they became the iconic representation of the female artist.

This leads me to Flashing Nipple Happening, Documenta XII (2007), Kelly’s Situationist-inflected reimaging of the flashing nipple street theater protest during the Miss World 1971 pageant in London. In the world of the female nipple, one is medical (the breast exam) or maternal, two are sexual, and those that come in multiples and blink electronically signal an airport strip club. The clip played by Kelly at the Hammer showed the performance’s female participants suiting up in all black, strapping on their female apparatus (suggesting-how could it not?-that it’s not the unity of the phallus that’s wanting, but the three-in-one of the mammaries + vagina), and hollering up and down a hill to dash, dance, and generally play banshee in the deep dark of a Documenta night. So the nipple (and cunt) flash flesh as esse, or spirit, and spirit as the trans-subjective, multiple “I am” that Woman has played as “im/age.” Thus serving up the female image as the con-textual “shield” that heroes look at that shields them from the brutal fact of their absolute negativity. L’homme n’existe pas. At the Hammer, Kelly said that when Post-Partum Document debuted, Rosalind Krauss told her: “This would have been fine if you had only done it as a book.” In this, Krauss forgot that books are not bound by their covers, or rather, that the book unbound and put in a frieze or set in a shield is still a book, and the writing on the wall is always text and context.

All works by Mary Kelly. Courtesy of the artist and Rosamund Felsen Gallery.

In a 1984 essay, Kelly asked: “How is a radical, critical and pleasurable positioning of the woman as spectator to be accomplished?”19 The question lies in its passive voice: “to be” betrays the allegorical gag (gag as in the thing stuffed in the mouths of many hostages and some sex partners. For in my Hammer experience of Kelly, she was articulating the narrative caesura inhabited by the work rather than exhibiting it. She became, in her retelling, that which so much of her work gestures towards but refuses to be: the blinking signifier of the signifying order. Not the master, because the master is nominally veiled in the cloak of mastery, the invisible cloak of the apparatus, but the more interesting overseer, the one (not one) who administers both apparatus and signification, who is responsible for and instantiates signification, but who is clearly working within an overt apparatus, meaning that the frame is overtly seen, and once seen, overtly capable of misconstruction. The multiple-in-one whose signature is everywhere in the sense of as-creation, but whose creations are up for grabs. Ready for dissembly. For mastery is not by nature, but by trade.20 In this, Kelly conjures the original Kantian Subjekt, the combined subjectus, a political or “legal” self, and subjectum, a private/interior self, which makes the possibility of a transcendent subject less romantic and (arguably) more imperative as a form of ethical and aesthetic exchange.21 If one is, one has an obligation to be.

Thus, inasmuch as Kelly’s work has masked, erased, rendered immaterial, linguistically conjured, and legerdemained the female figure, the female figure that stood before us at the Hammer, the female figure finally made by Mary Kelly, was Mary Kelly, icon and index. In the original English translation of de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1953), the “Childhood” section begins with the iconic line: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” In the book’s new translation, the line reads: “One is not born, but rather becomes, woman.” Kelly has made of herself that missing, yet ever present, misreadable “a.” Or, in her words: “Well, language is culture, right?”22

Vanessa Place is a writer and lawyer, and co-director of Les Figues Press.