Every artist has a breakthrough moment or two in her career. In retrospect, the year 1964 constitutes one such moment for Yoko Ono, who went on to become a major international figure of post-1945 global art.

That year, Yoko Ono was in Tokyo. Her stay in her native country after her return from New York was by then approaching two years. The sojourn memorably began with her solo concert/ exhibition at Sogetsu Art Center, the avant-garde forum in Tokyo, in May 1962. She made a strong impression in Tokyo’s vanguard circles and continued to maintain her visibility. She accompanied John Cage and David Tudor, her senior colleagues from New York, on a concert tour of Japan and performed with them in the fall of 1962. But the stress caused by the male-dominated art world and the curiosity of a conventional and patriarchal society toward a woman vanguard artist took a heavy toll on her: She voluntarily checked herself into a clinic to free herself from these pressures. In 1963, after leaving the clinic, she reorganized her life—divorcing the composer Toshi Ichiyanagi, marrying Anthony Cox, and giving birth to Kyoko. In January 1964, she resumed an active artistic life by participating in Shelter Plan, an event-performance staged by the vanguard collective Hi Red Center at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. By the fall of the same year, however, she decided to leave Japan for New York, the city she “missed so much.” Her departure from Japan turned out to be permanent except for occasional short term visits in the coming years.

If Ono’s life evolved significantly during the two years she spent in Japan, so did her art, as demonstrated by Grapefruit: Yoko Ono in 1964, a small exhibition at Ise Culture Foundation Gallery, New York (April 2-May 15, 2004). Guest-curated by Midori Yamamura, the exhibition intimately chronicles her artistic output in this crucial time period, encompassing a series of “events” she presented at the legendary Naiqua Gallery in Tokyo. These included the publication of Grapefruit on July 4th, 19664, which anthologized her “instructions,” two major concerts she presented in Kyoto and Tokyo before her departure and two postcard projects originating in New York (one was a Christmas greeting, or Air Talk in New York, which instructed the recipient to “keep smiling”). The display was copiously annotated by the artist’s own words as well as by excerpts from recent scholarly publications. Yamamura’s goal, stated in the press release, was to enable visitors to “examine the various cultural, social, and autobiographical elements” in Ono’s work and draw their own conclusions. Still, it is clear that the curator tacitly aimed at dismantling what she calls the “masculinist languages of Conceptualism and Fluxus,” into which the artist’s early oeuvre has been absorbed.

In a visually sparse presentation, consisting primarily of ephemera and documentary material, an unadorned volume of Grapefruit —the exhibition’s namesake—from 1964, occupies the place of honor. Unlike the subsequent, more popularized editions, which are often illustrated with the artist’s likeness, the 1964 edition merely bears a single handwritten word, the title, on a white, square cover. This utter simplicity befits the idea this book advances: language alone in the form of plain instruction could be a work of art. The notion of “event” based on an instruction—or “score”— is at once characteristic of Cage and Fluxus, although Ono puts it in practice in media that include the stubbornly object-reliant, such as painting. Furthermore, she does not claim that language could be a painterly material by fiat, but rather deconstructs “painting” step by step and gradually replaces paint with language, beginning with her canvas-made Instruction Paintings in 1961. Her deliberate exploration culminated in Grapefruit, which announces the infinite possibility of language in art.

Art historically, Grapefruit represents the purest possible form of conceptualism. That alone is an achievement that put her right at the center of a conceptualist revolution that was taking place worldwide. But that was not enough for Ono, who considers art not as an abstraction but as “a form of wish.” She must have known that the single-word instruction, say, to “cut” might be an elegant end-in-itself within the context of art, but its realization could add many more dimensions and meanings to it. In a sense, the whole exhibition illustrates her willingness to transcend the theoretical “degree zero” of conceptualism and create material and human manifestations of her ideas.

Take, for example, a group of works entitled Touch Poem. Touch Poem No. 3 is a purely conceptual (read, “imaginary”) event, designated to take place on March 33, 1964, in Nigeria. One often finds humor in Ono’s work, like in this imaginary exhibition piece (indeed Ono has recalled she was quite often “laughing to herself” when making art). The actual realization of the instruction, “touch each other,” took place on March 13 and April 2 at Naiqua Gallery, Tokyo. The filmmaker Takahiko Iimura recalls that some participants were initially tentative but soon “found their own ways of expressing the act of ‘touching,’” and they “all awakened [their] sensations by touching, which was rarely an issue in the art world.” Not only was the instruction fulfilled by the performance— and the work completed in a conventional sense through collaboration—but it also incited an original interpretation from an absentee participant, Nam June Paik, who phoned the gallery and “used the ringing sound . . . to touch the participants.”

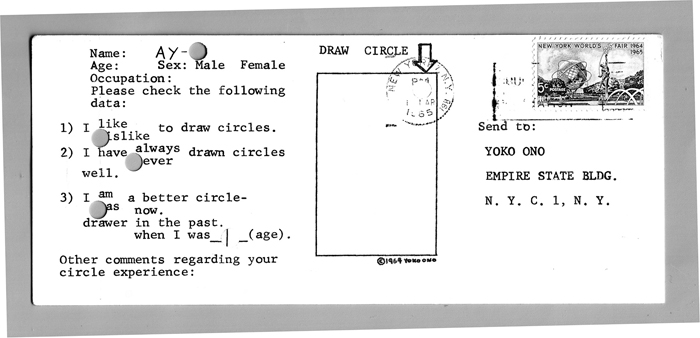

Similarly, the postcard-based Draw Circle Event, dated 1964 and executed probably in early 1965, prompted dozens of reactions to the unambiguous instruction to “Draw Circle” in a rectangle on each card. The exhibition includes the ten most “imaginative” responses from the artist’s collection. Among them are those of the composer Earle Brown, Tony Cox, Carolee Schneemann, George Maciunas, and Dick Higgins. The request induced a vital component of “audience participation,” provoking a number of intriguing responses: the New York-based Japanese artist Ay-O punched holes in lieu of the letter “O”, while leaving the rectangle blank; the Japanese art critic Shuzo Takiguchi contributed neatly drawn concentric circles, using “the small motor of a table juicer,” as he explained; and George Brecht reported he saw “a wet ring on the table.”

In these instances, “(interpersonal) communication” may be a better term to clarify Ono’s intent than the frequently used words “audience participation” and “collaboration.” Above all, her instructions are in and of themselves a means of producing a communicative act—the characteristic that strongly prefigured her antiwar campaign, which she began with John Lennon in the late 1960s, and has continued on her own since his tragic death. Since communication cannot be unilateral, the viewer’s involvement is more than a mere formality: both in theory and practice, it is indispensable. By framing her work as “communication,” Ono saliently called into question the modernist (and masculinist) notions of originality and authorship.

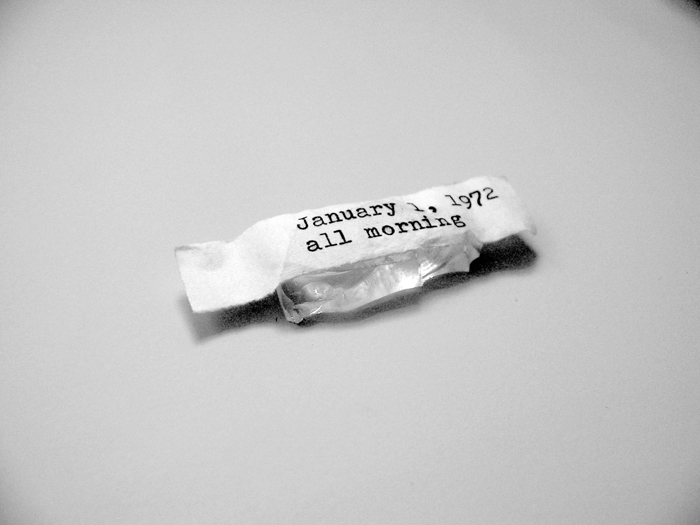

Communication is also an important element of Cut Piece, which premiered in Kyoto on July 20, 1964. In the Ise exhibition, the work is represented in its various manifestations, including a material “relic”; a clipped fragment of Ono’s dress from her farewell concert at Sogetsu on August 11. It was on loan from the estate of the Okayama-based woman artist Miyori Hayashi, which also provided another relic, a glass chip labeled “January 1, 1972, all morning,” which Hayashi purchased from Ono at an event called Morning Piece, staged at Naiqua’s rooftop on May 24, 1964. Hayashi’s relics are a rare art-historical discovery presented in the exhibition. The visual documentation, also displayed on the wall, includes a magazine clipping that reproduces a scene from the Sogetsu concert and a video projection of the film made at her solo recital at Carnegie Recital Hall in New York in 1965. And finally, the performance was re-enacted by a Boston-based artist Hiroko Kikuchi, as part of the Ise exhibition.

A feminist interpretation of Cut Piece has been long established. Indeed, as Yamamura writes in the catalogue, the work—in which the audience is instructed to cut pieces of the performer’s clothes by a pair of shears —has a definite feminist origin, inspired by the harsh criticism a male critic gave her, most likely in 1962: “Why don’t you just shut up and sit pretty?” By literally acting out the mean suggestion, Ono turned her work into an act of “ultimate giving”— akin to the benevolent Buddha’s throwing himself to a tiger as her prey. Ono’s paradoxical act, reinterpreted by Kikuchi four decades later, fundamentally centers on the issues of personal interaction and social contract. Tension is inevitably created by the use of a dangerous tool (scissors), even though the performer and the audience tacitly understand what is and is not acceptable. Performed in absolute silence, Kikuchi’s rendition of Cut Piece points to the enduring and evolving nature of Ono’s work.

Reiko Tomii, an independent scholar based in New York, studies post-1945 Japanese art in global and local contexts. Her recent text, “Historicizing ‘Contemporary Art’: Some Discursive Practices in Gendai Bijutsu in Japan,” appears in the Fall 2004 issue of Positions.