The Dash column explores art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. The dash is where the viewer comes to terms with what they’ve seen. Here, Carlo Tuason describes how pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong have imbued abstraction with the energy of a banned slogan, a battle of wills playing out online and in the streets.

Giraffe Leung, Paper Over the Cracks #6, 2020. Paint, tape, marker, and card. 10 ft. 6 in. x 6 ft. 10⅝ in. Courtesy of the artist.

In the summer of 2020, in the midst of pandemic-related chaos, China’s National People’s Congress voted unanimously to impose a national security law on Hong Kong, broadly criminalizing secession, subversion, acts of terrorism, and colluding with foreign forces, insofar as these and other actions can be deemed a threat to national security. The deliberate ambiguity of the law’s language played into local anxieties surrounding the extent to which the government was willing to go to crush dissent.

On the other side, the ability to demand attention had been crucial in the pro-democracy movement. The creation of spectacle through visually striking urban intervention was a common tactic, and stimulating and colorful images of their actions reached the covers of international outlets. As such, the passing of this law was implicitly yet unmistakably a targeted silencing of the protest movement. The popular protest slogan “光復香港, 時代革命” (Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of our Times) is itself illegal. In response, protestors have created abstract forms of protest art and imagery that attempted to circumvent these restrictions.

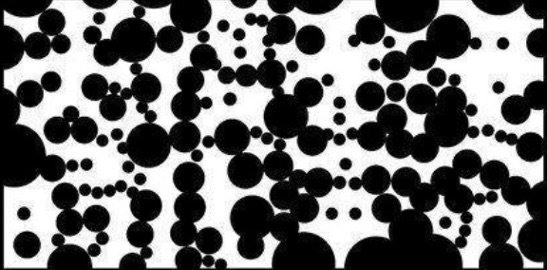

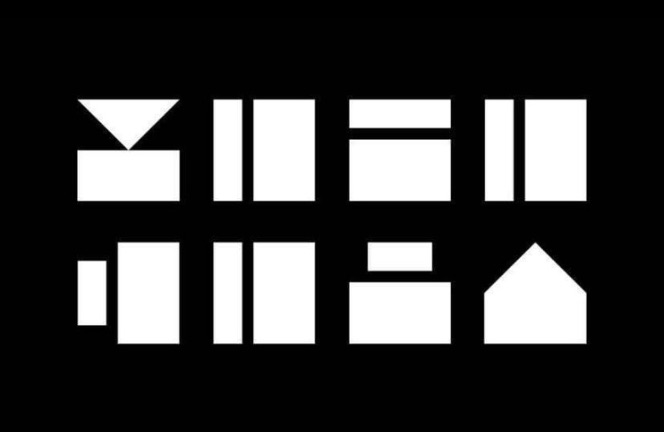

Anonymous, c.2020. Abstracted protest slogan. Digital image, dimensions variable.

The word “LIAR” superimposed upon the faces of local politicians, the revolutionary phrase from the movie Mockingjay (2014), “If we burn, you burn with us,” the common adage of support “Add oil,” and Bruce Lee’s “Be Water” are among the examples that made repeat appearances throughout the city. The heavily graffitied surfaces that spread throughout the urban environment of Hong Kong, layered with various slogans and sayings, were repeatedly torn down, painted over, and erased. But the act of erasing, the physicality of removing or otherwise covering up, leaves behind ghosts. In a sense, erasing is archive building, in that the space that was erased retains a certain residue of its former self in the form of shavings, indentations, smudges, and tears.

Giraffe Leung, Paper Over the Cracks #6, 2020. Paint, tape, marker, and card. 10 ft. 6 in. x 6 ft. 10⅝ in. Courtesy of the artist.

Giraffe Leung’s community art project Paper Over the Cracks (2020) highlights the mechanisms of erasure and silencing in Hong Kong by framing with bright yellow tape various instances where the city government removed or painted over graffiti. The haphazard paint job, the remnants of posters, and the stained surfaces from incomplete deletion serve as material reminders of the limitations of papering over dissenting messages to those walking by, through, and over. Leung’s title alludes to the superficial nature of the government’s failing attempts to adequately address various concerns of the city, including but not limited to policing and transparency. The literal act of papering over is an act of concealment; papering over the cracks creates a façade. Rather than attempting to actually fix the cracks or prevent more in the future—in other words, producing sustainable modes of governance—the government is prioritizing the aesthetic of stability.

Leung includes a small, museum-esque wall placard next to each of these installations, crediting the Hong Kong government as the artists of the work. Leung embraces absence in a way that amplifies the messages that were once there. Ironically, he has reframed the government’s acts of censorship as authoring an art of resistance. By listing the government as the maker, Leung rightfully forces the responsibility for the civil unrest onto those in power.

Anonymous, c.2020. Abstracted protest slogan. Digital image, dimensions variable.

Anonymous, c.2020. Abstracted protest slogan. Digital image, dimensions variable.

In reference to abstraction, another contemporary mode of disappearance active in Hong Kong, theorist Ackbar Abbas states in Hong Kong: Culture and the Politics of Disappearance (1997) that “the more abstract the space, the more important the image becomes (a point the Situationists also made), and the more dominant becomes the visual as a mode.” While erasure emphasizes the absence of the original, abstraction highlights the deviation from the original.

Leading up to and following the implementation of the national security law in Hong Kong, a variety of digital protest art was anonymously created and heavily circulated online in meme-like fashion on platforms such as Telegram and LIHKG. Many of these images, produced anonymously, employed a variety of techniques to abstract and obfuscate the now-illicit protest slogan into ambiguous yet identifiable shapes and patterns. One of the more well-known and widely disseminated examples reduces the Chinese characters to graphic geometric shapes, simplified visual representations that allude to the various radicals—base components that comprise Chinese characters—that constitute the slogan. The creator of the image, relying on the iconic, visual recognizability of the text, allows for the legibility of the non-present political message. Another example employs a similar technique of geometric simplification, digitally altering the image in a manner that evokes smudged, swirled ink. The digital mimicking of a physical, materially based act of distortion functions, in a way somewhat similar to Leung’s gesture, to reinforce the notion that what is removed or made illegible still exists, perhaps even more potently than before.

Anonymous, c.2020. Abstracted protest slogan. Digital image, dimensions variable.

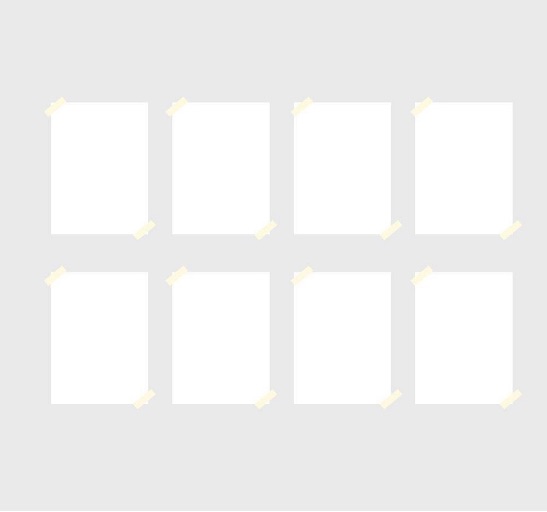

Once the national security law came into effect, residents of Hong Kong were forced to negotiate the complexities of such deliberately amorphous policy. One technique employed was the use of blank sheets of paper as protest signs. This was not limited to the streets, but was also utilized by pro-democracy legislators in the city’s Legislative Council. As Asbjørn Grønstad and Øyvind Vågnes write in Invisibility in Visual and Material Culture, these blank sheets of paper, this invisibility of text, this absence, “can appear to linger at the threshold of utterance, as what is said not explicitly, but perhaps implicitly,” or what some may refer to as “reading between the lines.” Such a reading—the liminality of being both invisible and visible—is central to the impact of these images. These blank sheets of paper have themselves become iconographic and can also be seen in digital protest art of a similar nature; in lieu of graphic text, eight blanks in a two-by-four grid stand in place of the banned slogan’s characters.

There is power inherent in being seen and heard, and similarly, in being able to see and hear others. Accordingly, the national security law governing Hong Kong actively limits visibility. Hong Kongers have responded to such restrictive measures by embracing absence, and in doing so reframe the act of censorship as illustrative of the government’s own shortcomings. Further, in creating these semiotics of resistance in the wake of popular expectation, Hong Kongers have expanded the terms of their own visibility. x

Carlo Tuason is a curator, writer, and musician.