For the re:Research column, we ask artists to take us behind the scenes of their work. Here, Olivia Erlanger recalls the unforeseen chain of events that led her to make Portrait of the Baroness, a meditation on privilege, identity, and (missed) translation.

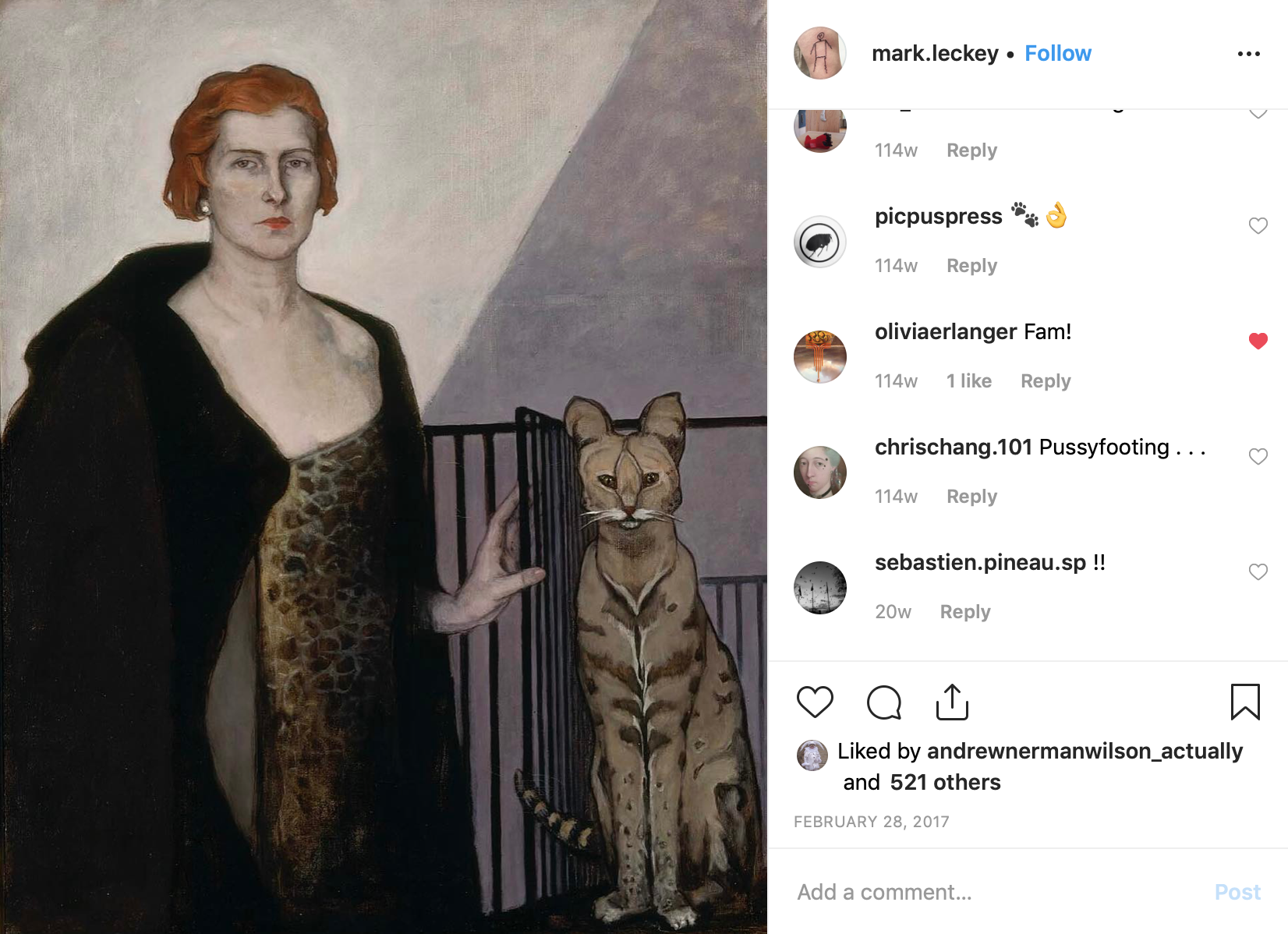

Screenshot of Romaine Brooks’ Portrait of the Baroness D’Erlanger, 1924, posted on Mark Leckey’s Instagram, February 2017.

Sitting in a Tunisian jail, all I could think was that I blamed Mark Leckey. One night in February 2017, I saw a photo Leckey posted to Instagram of a painting titled Portrait of the Baroness D’Erlanger (1924) by Romaine Brooks. Brooks was an American portraitist who spent most of her life painting aristocrats in Paris and Capri. Known for her angular style and palette of slate greys and dim blues, Brooks rendered the stately Baroness with wild orange hair. A confident woman, she looks boldly out of the frame while standing beside a hyper-stylized ocelot. As I was falling asleep in the blue light of my cell phone, a distant connection formed in my mind. My last name is Erlanger, hers was D’Erlanger. Could these be the relatives I had been told were lost long ago? I wrote a short comment on the image (“Fam!”) and fell asleep.

My father raised us with a story. “Here, we are us,” he would say as we looked over the antiques that his mother Olga, an antique dealer, left him after her death. “But before leaving Europe, we were nobility.” Did this describe a true fall from grace? Were we, middle class Jews living in New York and the suburbs, once a part of the upper echelons of Continental society? Or was this a grand fantasy woven to fill the absence of two generations of history that had been left behind? The shape of this narrative is common to Americans, where a flame that warms the present generation is lit in the collective imagination by the fabrication of one’s past.

The empty swimming pool at Ennejma Ezzahra, Tunis, Tunisia, July 2018. Photo: Oliver Lanzenberg.

Why would we want to be another family? The D’Erlangers were rich. Their wealth was derived from the bank established by the patriarch, Raphael von Erlanger, in 1848. As converts from Judaism to the Protestant faith, in two generations they had escaped the restrictions of the Frankfurt ghetto and all opportunities were now open to their sons and daughters. A banking family, they became crypto-Jews by dismissing their aquiline Ashkenazi features and buying a French title. That D’ was enough to secure land, money, access, and wealth. The Hebrew letter “D” is daleth, meaning doorway. The daleth sits in the middle of the word for Eden and symbolizes the way in which one could both enter and exit paradise. One more Google search and I discover Ennejma Ezzahra. Ennejma Ezzahra, or Star of Venus, is the name of the palace the D’Erlangers built in Tunis, the capital of Tunisia.

Six months passed. The story became a party trick that I deployed when all other anecdotes were used up. I’d show the painting of the Baroness and then an image of the palace. People would laugh. But when I mentioned this story to a friend from Tunis, they explained that the Maison D’Erlanger was in fact very well-known and that they’d be happy to introduce me to a local foundation who could help fund a research trip.

In July 2018, as the staff walked me around the Maison D’Erlanger, playfully calling me Olivia D’Erlanger, it felt like my Princess Diary moment had finally come true. Built in the early 1900s, Ennejma is a blend of architectural styles taken from Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and elements from the larger Arabic diaspora. The D’Erlangers’ romanticized, orientalist perspective, and their self-declared right of ownership of all of North Africa, is clear in this hybridized palace. It is a fantastic space. None of these styles or motifs would likely be deployed all together, save for in the mind of an outsider looking in. The walls and ceilings of the rooms are fabulously ornate, with hand-carved patterns and recessed alcoves covered in gold leaf. And at the same time, as in many small museums, upon closer inspection the furniture is dilapidated and threadbare. The interior fountain had fallen from a marble scallop shell carved into the wall. I found out that most of the actual objects that the family owned had been taken out of the house by the real D’Erlangers’ progeny. A lot of the furnishings came from thrift stores that had been reupholstered by one of the researchers devoted to the family, a Welsh woman named Winkie, in what she liked to describe as a style that recalled her bohemian college days in the 1960s.

Yet the more I learned about the family, the less interested I became in being part of their story. The D’Erlangers created a cotton-backed commodity bond that helped fund the Confederacy during the US Civil War, and banking protocols they put in place in the early 1900s helped bankrupt Tunisia. By the time my genealogy was done, I was relieved to learn there was no connection to me at all save for my father’s tall tale. A lot more stood between us than the daleth after all.

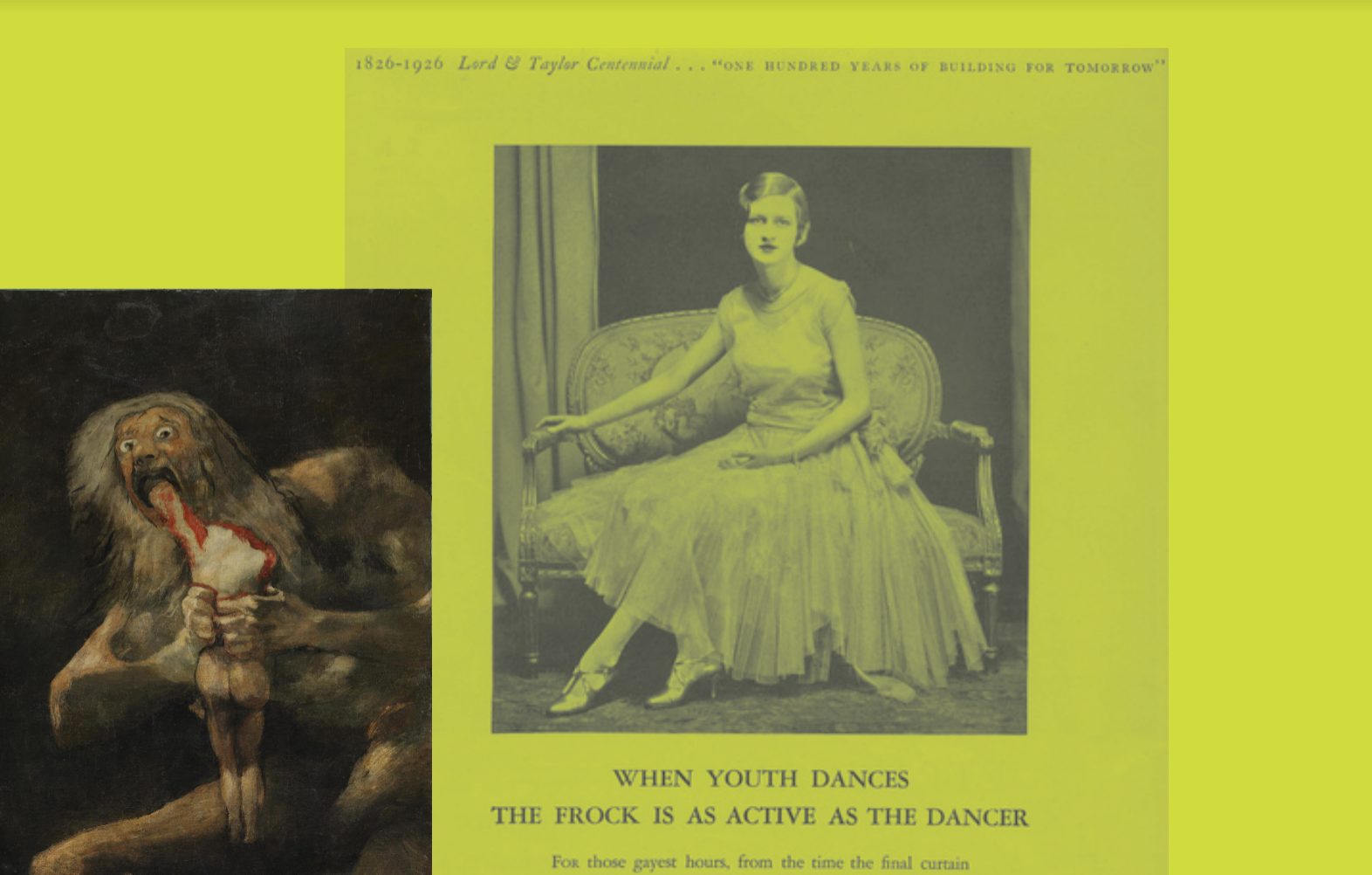

A page from Olivia Erlanger’s proposal to Kamel Lazaar Foundation for funding, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.

This could’ve been the end of the story. And maybe it should have been. After all, why endeavor to create a project that is based upon a lie and potentially publicize a deeply fraught name in the process? Instead, I pushed forward with a proposal to the foundation that funded my initial trip for a video project that would explore identity as a form of myth making. The slick PDF included reference images collaged on a lime green background. I tried to reorient the project away from the D’Erlangers. After all, the thread that attached us was more universal: the art of storytelling. “The purpose of the project is to explore a set of relationships that interrogate the construction of, and potential for, the implosion of personal narratives,” I wrote in the proposal. “How does the exportation of western imagery act as a means for domination and control? How does this operate within this interrogation of identity, specifically in representations of women?” It looked professional enough and had the appropriate buzzwords, despite being open ended. All the locations I chose were related to different mythological sites. Djerba, for example, an island off the Tunisian coast, is reportedly The Island of the Lotus Eaters from the Odyssey. Neopolis, an ancient sunken city newly discovered in 2017, is a proposed location of Atlantis. And in the South we would travel to Mos Espa, a fictional desert town in Star Wars, the sets of which remain standing in the Sahara. We would interview people on personal mythologies and old wives tales, and I’d create an archive of stories that cut across specific differences, describing a globalized constellation of connective narrative tissue. The commission was quickly approved. I hired a cinematographer, rented an Amira camera, forwarded my location list, and felt as ready to go as I could.

For our first shoot, cinematographer Oliver Lanzenberg and I chose a site that looked more or less abandoned to test the camera and to feel out how we would work together. We had been there for all of thirty minutes before a Mercedes-Benz barreled out of the corner of the property and towards us. Three men in aviators screamed at us, in a mix of Arabic and French. “What are you doing? How did you get here? Is that a sniper rifle?” Struggling to get a word in, Oliver translated in French as I said, “I am an artist. I am here to make art.” But my salvo was lost on them.

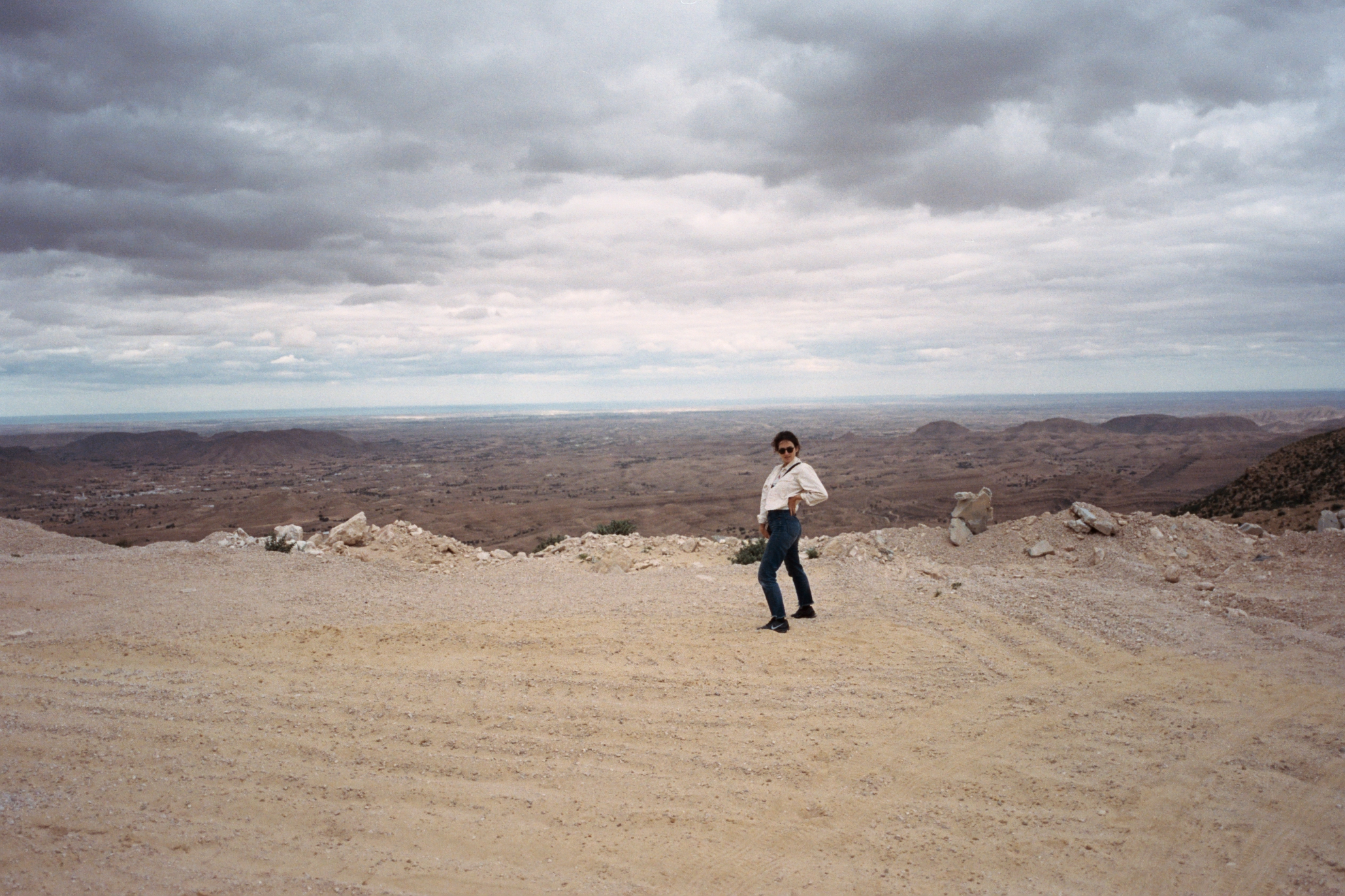

Olivia Erlanger on location in Toujane, Tunisia, 2019. Photo: Oliver Lanzenberg.

Olivia Erlanger and friend Kaïs Dhifi filming on location in Doiret, 2019. Photo: Oliver Lanzenberg.

A forewarning from my Tunisian contact that any camera bigger than an iPhone would get me detained was very clearly lost in translation. And in fact, even using an iPhone in public is enough to get you questioned and detained by police. I had also been led to believe by my casual discussions over email and at parties that filming permits were unnecessary. This was another obvious oversight.

“Art?” They laughed. “What the fuck are you talking about? This building is on the road to the presidential palace. In two days there is a Pan-African Conference where the leaders of every African country will be driving down this street. New Zealand just happened. White Nationalism. Trump!” And with that, I realized I was being accused of being a spy, a suspected white nationalist terrorist—and that the privilege endemic to my white skin and American passport had made me feel entitled and safe. Who was I to think this could be a casual endeavor? My presence itself was political, and my actions pushed this further. Even if they knew it was a camera, not a rifle, cameras meant journalists—and journalists meant fake news, negative attention, and potential danger to the people portrayed.

Two undercover cops joined us. And then an army lieutenant. More cops and more army men. I looked around and counted ten men and one armored van. A van. This was probably the height of my despair. I started laughing and screaming. We didn’t end up in the van, but it didn’t matter: we soon found ourselves sitting at the police station trying to explain that, while mine and my cinematographer’s names both translated to “olive,” or Zaitouna, the national symbol of Tunisia, these were not shitty cover names but rather a coincidence.

Olivia Erlanger being interrogated at a police station in Tunis, Tunisia, 2019. Photo: Kais Dhifi.

“I make sculptures and video,” I explained again. But I slowly realized that our realities would not intersect. The bad film noir-style detective pointed out the fatal flaw in my story.

“It is a lie! Sculpture and video? You see! You can’t do both.”

I sat shocked. This detective had just hit the core of my insecurity, the root of my self doubt. As a sculptor who is also an author who is also a documentarian, this statement was the triangulation of my biggest fears.

A few hours later, with the help of many Tunisian friends who advocated on our behalf, we were allowed to leave. And with that, the shoot had begun. Our lack of permits meant we only made it to three of the original seven locations I had planned to document. In the end, however, the project is indebted to this error, as we had to become more inventive and flexible, responding to our surroundings rather than holding tight to our original, ultimately fantastic plan. Sometimes, especially while working on a documentary, you have to completely let go of the need to control.

The new sites that we were able to capture go beyond the clichés of my first proposal, which located Tunisia through the eyes of a tourist. Walking past an abandoned hotel, we struck up a conversation with the security guard. He informed us that this was a hotel built for German tourists on the ruins of an old synagogue. The red walls and the domed golden ceiling of the synagogue were partially maintained as they poured a foundation and built the floors above it. Tunisia had had a robust tourism industry in which droves of Germans, English, and French people would summer on its gorgeous beaches. First, the Arab Spring in 2011 slowed the flow, and then two consecutive terrorist attacks, one on the beach and another at the Bardo Museum, basically stopped it altogether. In the years since, the industry had fallen apart and all of the super hotels that were being built were left to ruin. Unfortunately, the stories of these attacks still shade the Western perspective of Tunisia, and help to percolate and spread fear of a country which is one of the most stable, most secular, and most liberal in North Africa. The German resort was abandoned mid construction, half synagogue and half hotel.

Apollo with his nose and phallus removed at Bardo National Museum, Tunis, Tunisia, 2019. Photo: Olivia Erlanger.

This convergence of identities is common in Tunisia. First came Judaism, then Christianity and Islam. People there say they are Mediterranean, Phoenician, Maghrebi, Berber, African, and Arab. As each power took hold, they attempted to erase the stories of those prior. Noses were cut from statues. Phalluses too. Yet more recent French colonialism and American imperialism, while obviously deeply destructive, have not erased or homogenized these identities to the same degree. Fluid and multifarious, the individual realities that contemporary Tunisians shared with me created a new and unforeseen constellation for the project. Yes, I believe the challenges I faced in attempting to answer the question, “Who am I?” were in some ways karmic. Extrapolating within a larger architecture of lies—from the original story of my family’s lost grandeur to a false connection to a palace, to trying to create an artwork in a country that is ultimately not for my consumption—is wont to explode. Exploring the identity of a lie, or a lie of an identity, is wont to implode. x

Olivia Erlanger choreographs ultramodern environments through installations, videos, and writing that show how advanced technologies engender subjectivity. Alongside curating exhibitions as a founding director of Grand Century, New York, Erlanger has held solo exhibition with Mother Culture, Los Angeles; Human Resources, Los Angeles; AND NOW, Dallas; What Pipeline, Detroit; Mathew, New York; Balice Hertling, New York; and Seventeen Gallery, London. Erlanger recently published Garage, a history of the deprogrammed garage space, with MIT Press.