For the Re:Research column, Megan Plunkett tells the story of her time as a student of forensic photography, an experience that fed the paranoid, paranormal thinking behind her show Electric Avenue at Emalin in London, July 30–September 11, 2021.

Found images, 2021.

Cameras

In an exhibition essay for my recent show, Electric Avenue, 2021, my friend Zachary Furste introduced me to a new word: the German zuhandenheit, which translates to something like “readiness-to-hand.” This is a great word, and it begins to describe my relationship with my main material squeeze, the camera.

I never had the kind of storied relationship to a camera that photographers seem to have—the darkroom love song and all. But I consider myself an image-based artist above all, and cameras are often the best means to that end. Cameras are just machines we manipulate with our imperfect human hands; my eyes are in my body, which is just a thing that moves through space.

Still from “Will the Real Martian Please Stand Up?,” The Twilight Zone, 1961.

In late 2019 and early 2020, I decided to do coursework in crime scene and forensic imaging. I had a few inspirations for this.

Authority is an aesthetic problem as much as anything. What kinds of visual authority do we heed, what do we ignore? I’ve always loved what Douglas Eklund wrote in the 2009 Met catalog for The Pictures Generation, 1974-1984, about how images mirror the ways in which the world “ease[s us] into a constant crisis of authority.” I agree, but now it’s 2021, and the ways that images push on us has only intensified since the time of his writing. High time to keep figuring out ways to push back.

Lynne Cohen, Military Installation, 1994. Silver gelatin print, ed. of 5, 29½ x 37 in. Courtesy of the Estate of Lynne Cohen and Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto.

My teacher was a retired cop. He spent most of his career in Sacramento, the same city where I used to work trimming weed. I guess in the end we had both really walked the line of legality in our great state’s capital, although this was information I chose not to share with him. I recently sent my class binder, which I turned in at the end of the course to get graded, to DREI in Cologne for a small group show. It is the only time I will show that thing publicly.

I wanted to be forced to do technical exercises and feel how my hand was affected by rigid and prescriptive directives for making an image. I have always been very attracted to the traditions of technical photography, and to the “limits” of how a given image functions in the “real world.” Bringing legalese into it felt appropriate. Historically, photographs have lured us with the promise of a kind of almost forensic objectivity, but they are also only a pause in time’s unfolding, a series of motions that unavoidably produces an estrangement of realism.

If I believe that an image is a stop the mind makes in between uncertainties, then what could crime scene imaging have to tell me about that?

NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover took this image overlooking the Séítah region using its navigation camera, July 7, 2021.

Things and Objects: Invaders and Intruders

One of the incentives for the series of works I eventually called “The Invaders” and “The Intruders” is my interest in “haunted media,” a term coined by cultural historian Jeffrey Sconce. Born from an often-American hang-up of reading paranormal or otherwise spiritual phenomena into our experiences of communication technologies, the feeling is often rooted in, broadly, “a fascination with the boundaries of space and time,” which usually devolves right into a more generalized anxiety about our agency within “the system…”

Different, but in some ways the same: we could say that many early American photographic innovations were born of aims like trying to contact the dead.

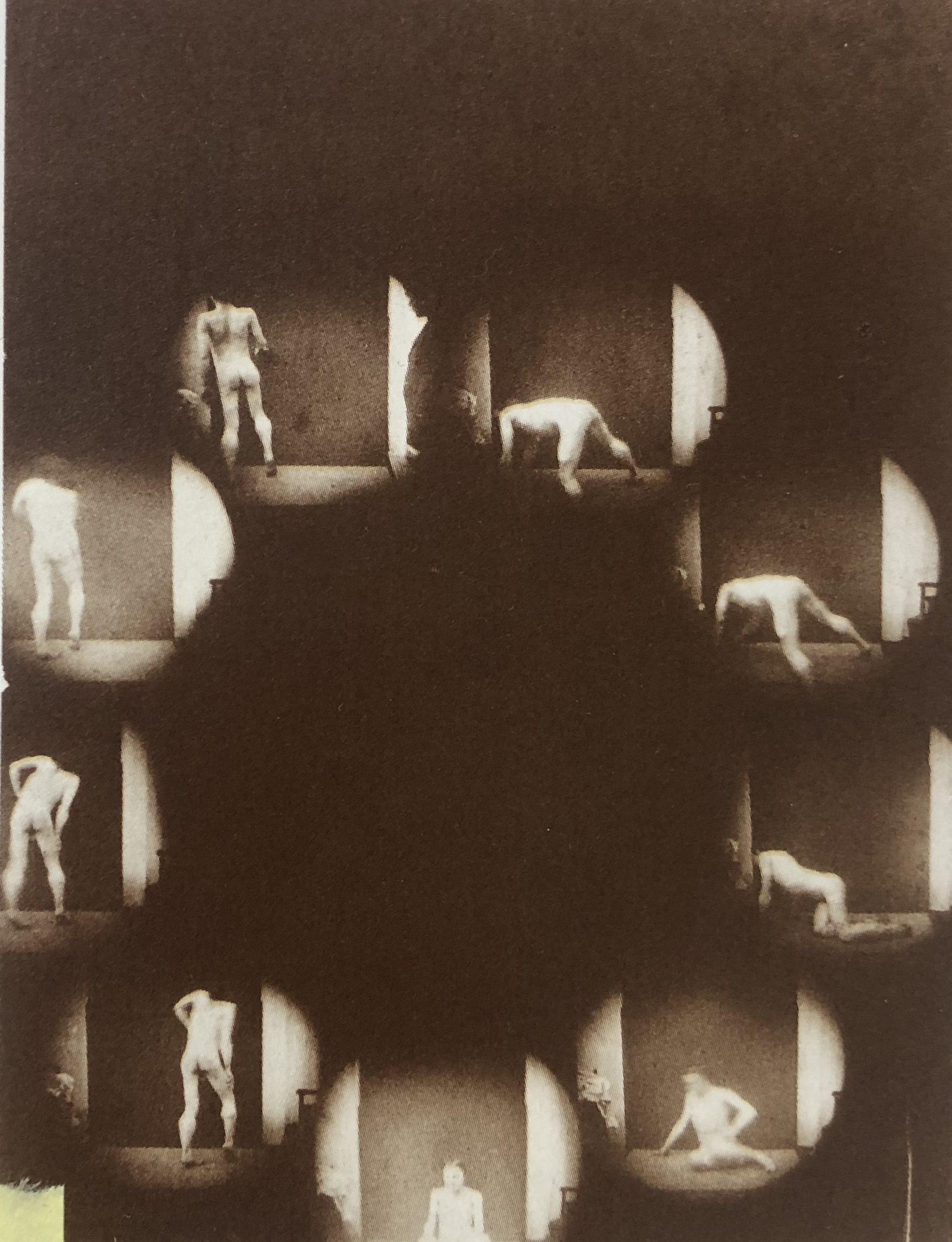

Albert Londe, Study of Pathological Locomotion, 1883. Public domain.

In the studio, I keep an ongoing “big board”: lists of objects, phenomena, and found images that I throw up there and shuffle around. These are the elements that lurk around and eventually form my own images.

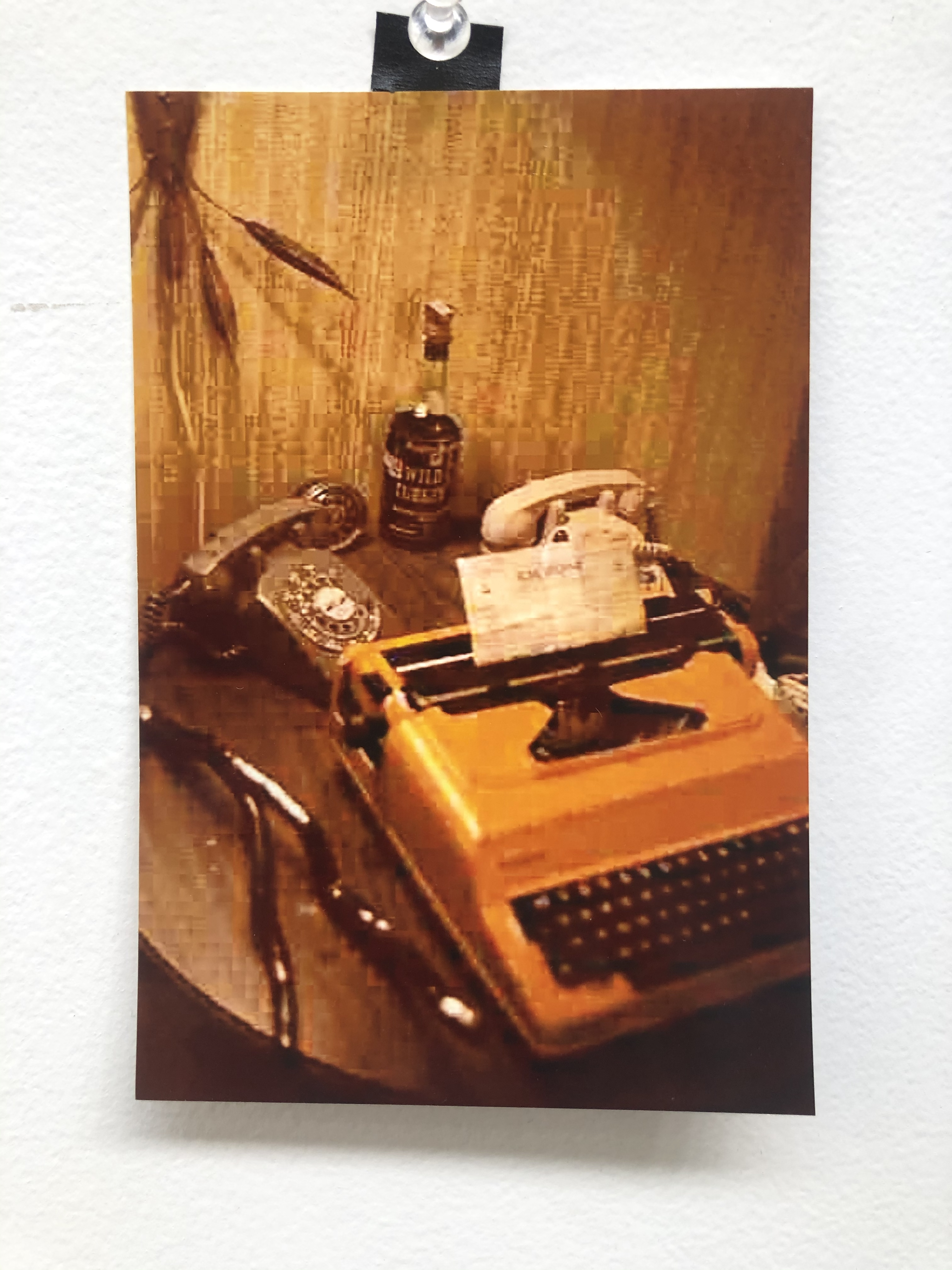

At some point, a phone became an object that I got hung up on. A phone is a perennial cinematic device that very directly embodies distance and presence. Later on, I found a photo in the Los Angeles Police Department’s archives that was taken in John Belushi’s hotel room at the Chateau Marmont. It isn’t a particularly interesting image, except for the doubled phones on the desk. It seems like such an obvious analog thing to do when you stop to think about it, and I knew that was my way in.

Copy of LAPD photograph from John Belushi’s hotel room, 1982, pinned to studio wall.

I started shooting in hotel rooms, spaces that are themselves a bit of a prop, with phones that were native to the rooms as well as cadres of rented phones from a local prop house.

While unpacking and setting up the first of several shoots, I found this note I had written and stuck in my notebook sometime during my forensic class:

- The resting places of a thing

- Distance

Megan Plunkett, The Intruder 01, 2021. Digital c-print on glossy paper, 12 x 18 in. (image), 20 x 26 in. (framed). Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London.

I shot the phones in the rooms in bursts, bracketed images taken in bulk using wildly different and highly manipulated lighting. Post-shoot, I combed through to locate the most interesting lights and shadows, then combined them into one final image: a mesh of masks, magnification, and misdirected attention.

Zachary Furste: “Just as soon as we reach out a hand, an uncanny surplus emerges. We count more headsets than phone cradles… The images are split, doubled, shot through with the unreal. Our embodied desire for connection runs up against uncanny leftovers. We feel something like inter-dimensional vertigo.”

Megan Plunkett, The Invader 03, 2021. Digital c-print on glossy paper, 10.5 x 16 in. (image), 18.5 x 24 in. (framed). Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London.

The Matching Image: The Hammers

One handy concept I learned during my class is the idea of the “matching image.” In forensic jargon it applies to images that show how things once were, a way of demonstrating past action in visual shorthand. Put another way, as Zachary writes, matching images are, very literally, “faked photos that acquire the force of law.”

The gathered mass of hammers in Electric Avenue is my kind of matching image.

Hammers, test prints in studio.

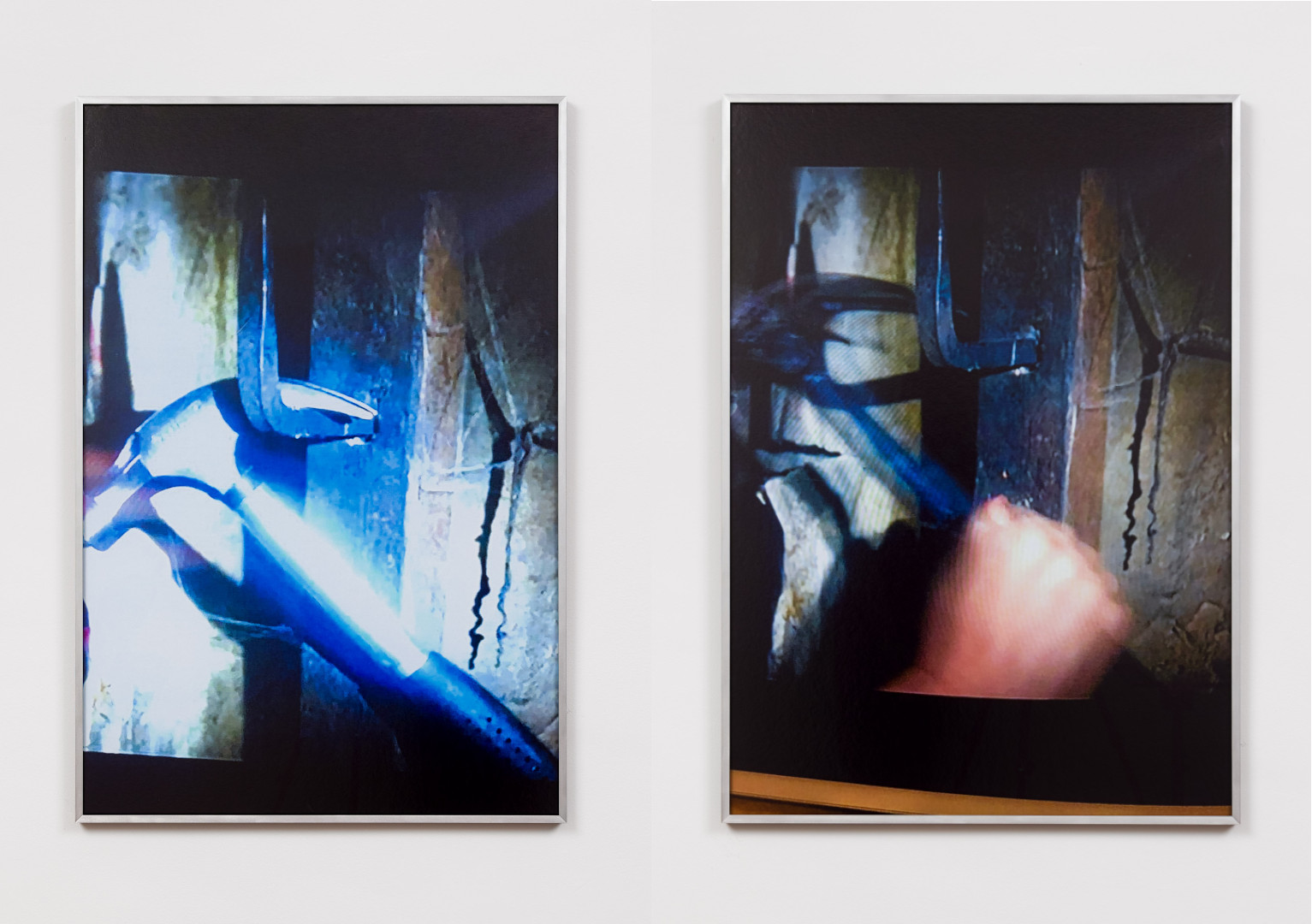

The “original” pair—the works later called The Hammer (Left) and The Hammer (Right)—is a set of screenshots showing a hammer being taken off the wall in the original Hellraiser (1987). Working under the cover of “genre” tropes can be an avenue for expressing the very personal. This is something that I had always intellectually understood but did not emotionally know until semi-recently, and Hellraiser is a movie that always reenforces this for me.

Left to right: Megan Plunkett, The Hammer (Left), 2020–21. Digital print on glossy paper in aluminum artist frame, 27 x 40 in. Megan Plunkett, The Hammer (Right), 2020–21. Digital print on glossy paper in aluminum artist frame, 27 x 40 in. Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London.

The second set of hammers, a series of five smaller image works I just called “The Hammer,” were shot in the studio using an iPhone 8. I set out to make a match for the first pair, and found myself with these. I set up three hammers on an old wood table against a white studio wall. One hammer has some black gatorboard under to maintain balance for a wobbly handle. I threw a black cloth around the trio to drown out overhead LEDs, and also function as an ad-hoc “in-frame” frame. I used the panorama function and dragged my arms around, narrowing in on the strange doublings and compressed space with each pass. I love what a panorama does to space (again, distance, the resting place of these objects). I love that so much imagery of deep space has to rely on panorama for us to understand incomprehensibly vast spaces, highlighting again the “big ones”: How big is this and where am I? (Who am I?)

The final image is littered with hidden duplicates and deceits: a reminder that a good image always tricks me back. X

Megan Plunkett is a Los Angeles-based artist. Recent shows include Electric Avenue (Emalin, London, UK), Act Naturally (The Gallery @ [now Stars], Los Angeles, CA), and Return to Sender (with Barbara Ess, F, Houston). Group exhibitions include shows at Gaga Reena, Shoot the Lobster, Magenta Plains, Redling Fine Art, Sweetwater, Bad Reputation, and Mitchell-Innes and Nash, among others. Plunkett is the cofounder of The Kingsboro Press, an independent publishing banner who’s most recent imprints include “The Wainwright Naked Hippie Tarot” and a pressing of a previously “lost” Cookie Mueller and Glenn O’Brien play, “DRUGS.”