The Dash column explores art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. The dash is where the viewer comes to terms with what they’ve seen. Here, Cara Schacter dips into her heart-healthy fascination with the oatmeal influencer account Trace’s Oats.

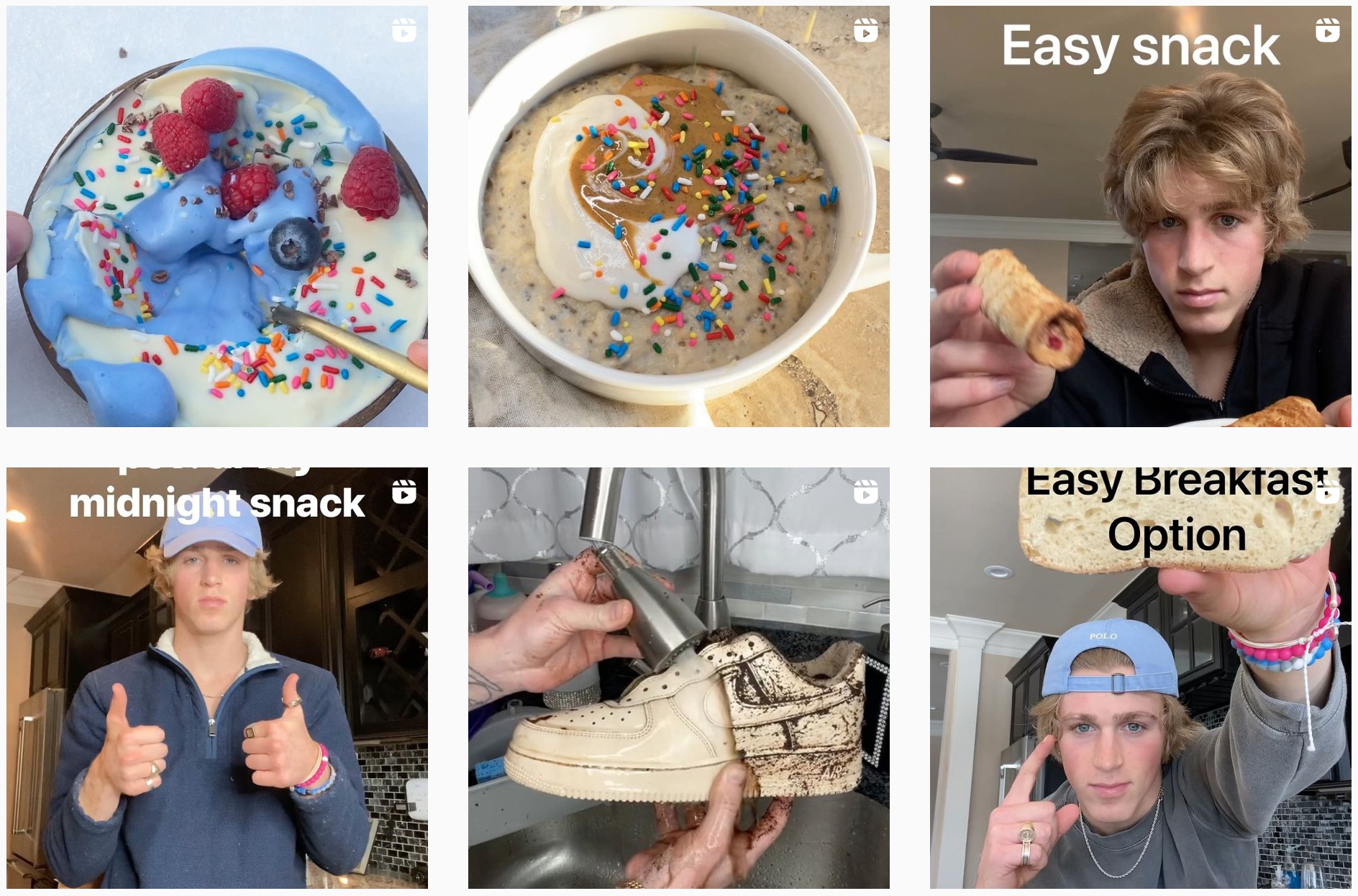

Screen shot of @tracesoats on Instagram.

“Hot cocoa oats (hot cocoats). See what I did there? Also, THAT OAT CLIP IS FUEGO.” Trace captions a bowl of rolled oats mixed with cocoa powder and mini marshmallows. Trace is an oatmeal-focused micro-influencer with two hundred thousand Instagram followers. Positioned as recipe inspiration, the effect is more hypnotic than innovative—reels punctuated by jump-cuts and crisp acoustics: raw oats hitting a Pyrex bowl, an apple diced with anapestic aplomb, a dollop of Greek yogurt slapped on top.

Overblown presentations of mundanity have long been the purview of realist art, with displays of workaday victuals maintaining a stronghold on the form. In a profile of German photographer Thomas Struth, Janet Malcolm writes about the luncheonette pies of 1960s photorealism enlarged to “an arresting, sometimes almost comical degree of visibility.” Thomas Struth—not a photorealist—doesn’t see the point: “They are only trying to show they can paint,” he tells Malcolm, which is “not art.” Malcolm is quick to point out that “Struth, of course, was mischaracterizing the photorealist project—which was not to display painterly skills but to cast a cold eye on the psychopathology of mid-twentieth-century American life.”

As Trace (and the legion of analogous accounts) magnifies granular experience, presenting breakfast in all caps, he offers a reversed kind of realist derangement—one not explicitly displayed in the content but folded into its creation and reception. Instead of casting cold eyes on the psychopathology of mid-twentieth-century American life, in the twenty-first century, we cast psychopathological eyes on benumbed digital life: manically stitched footage of refrigerated overnight oatmeal mixed with protein powder paired with a sound clip from the Black Eyed Peas’ “Boom Boom Pow.” If the ’60s were about enlarging elements of quotidian life to an arresting, almost comical degree of visibility, today the element being arrested to a comical degree is the act of viewing itself.

Screen shot of @tracesoats on Instagram.

A poll posted to Trace’s stories asks: “PB & J for breakfast type of morning?” with the option to vote “YES” or “BOI WHAT.” It’s easy to write off the hype-ification of the unremarkable as desperate junk in a culture of substanceless content creation—but somewhere under the recessed lights of the suburban kitchen there is an essential ambrosial delight to the inflation of the everyday, however intellectually offensive.

“Do you feel you need to put large meanings into your work?” Malcolm asks Struth. Struth says he wants to do more than “just photograph flowers.” Malcolm presses further: “I’m trying to elicit from you what the more is.” Struth struggles to respond. “The more is a desire to melt, like to—how can I say it?—be an antenna for a part of our contemporary life and to give this energy, put that into parts of this narrative of visual, of sort of symbolic visual expression…” Struth trails off. He never pins down “the more,” melting into his own attempt to explicate it. So where is the line between pointlessness and art? What’s the difference between speaking the unspeakable and saying nothing at all? At what point does “just photographing flowers” or, say, oatmeal go beyond mere documentary to capture the energy of contemporary life under the redemptive reach of art?

While trying to square my compulsion to consume hours of vapid oatmeal content with a Struthian regard for the ambiguously profound, I went to see the recent work of Catherine Murphy, reportedly “one of America’s greatest living realist painters” and specialist in the “modest sublime.” Her exhibition at Peter Freeman gallery is a mix of still lifes, landscapes, and self-portraits. In Packed (2018), a pair of striped button-up shirts in an open suitcase is painted with such striking lucidity, the difference in the light’s refraction off the pearlescent white plastic of the shirt buttons versus the matte black plastic clasps of the luggage straps seems a sobering truth; monumentally small (“that really is how things are,” you marvel). The New Yorker compares Murphy’s play of light on a pair of trash bags to seventeenth-century French painter Chardin—a parallel that, via Proust, might in fact loop us back to Trace and his oats. In “Chardin: The Essence of Things” (1895), Proust addresses a young bourgeois boy who sits at his family dining table, considering the detritus of their meal, and feels something “not far from depression” as the sun hits his glass of water only to accentuate “cruelly as an ironic laugh the everyday banality of this unaesthetic sight […] this scene of domestic mediocrity.” To this boy, Proust proposes a trip to the Louvre. Specifically, he guides the boy to Chardin: “In rooms where you see nothing but the expression of the banality of others, the reflection of your own boredom, Chardin enters like light, giving to each object its color, evoking from the eternal night that shrouded them all the essence of life.” The familiar, lit correctly, dissolves into the miracle of the commonplace.

Trace’s bio is a consecration of the cereal grain: “Perfect has seven letters… so does Oatmeal.” He’s not saying oatmeal is perfect, just that they fill the same amount of space. Sometimes on the granite countertop of his parents’ kitchen, I see the reflection of a ring light like a halo for a gleaming slab of existence.

Screen shot of @tracesoats on Instagram.

When Struth says photorealism is “not art,” he suggests the aesthetic value of an image lies in its ability to offer something beyond the pedestrian frame of reference—“the more.” There is a stilted awareness of the camera lens in his photos, an insistence that viewers not only reconsider things as they are but reconsider consideration. Take his museum photographs, a series that looks at people looking at art. In Galleria dell’Accademia I (1992), a long exposure blurs visitors into smudges of t-shirts and fanny packs as they move about a vast Mannerist panel of Christ feasting. Nebulous gallery-goers contemplate Jesus’s buffet at quaalude speed.

Trace is a fixture in the orbit of characters I get sucked into when I open my Instagram Explore page and let the algorithm take me. In “Going Postal,” Max Read posits that participation in social media stems from a desire for “not death, precisely, but oblivion—an escape from consciousness into numb atemporality, a trance-like ‘dead zone’ of indistinguishably urgent stimulus.” Fugue has two meanings. In psychiatry: a state of loss of awareness of one’s identity. In music: a melody introduced by one part and successively taken up by another. A fugue is both a separation from the self and a collective composition. Art critic Peter Schjeldahl once called Robert Bechtle’s 1974 photorealist painting of a Ford station wagon parked in a suburban driveway “a nova of banality.” Novae happen when a celestial body increases in luminosity to as much as one hundred thousand times its baseline. To “go nova,” a star steals gas from a nearby companion.

I watch Trace make oatmeal to dim myself. Maybe that’s not arid internet loitering; maybe that’s luminary participation in a contemporary realist project. A desire to melt. Yesterday, Trace posted: “Snow oats… SNOATS (if you do this, boil snow for 5 minutes to sterilize).” X

Cara Schacter is a writer living in New York.