The Dispatches column presents reports and diatribes from the front lines of contemporary art. As lengthening fire seasons takes hold of California, turning the hillsides black and the sky orange, Renée Reizman surveys two arboreal Los Angeles exhibitions—Glenn Kaino’s A Forest for the Trees (May 13–December 30, 2022) and Stanya Kahn’s Forest for the Trees (June 4–July 16, 2022)—where the trees are the stars. Can empathy for our leafy fellow creatures spur us to climate action, where concern for our own survival has failed?

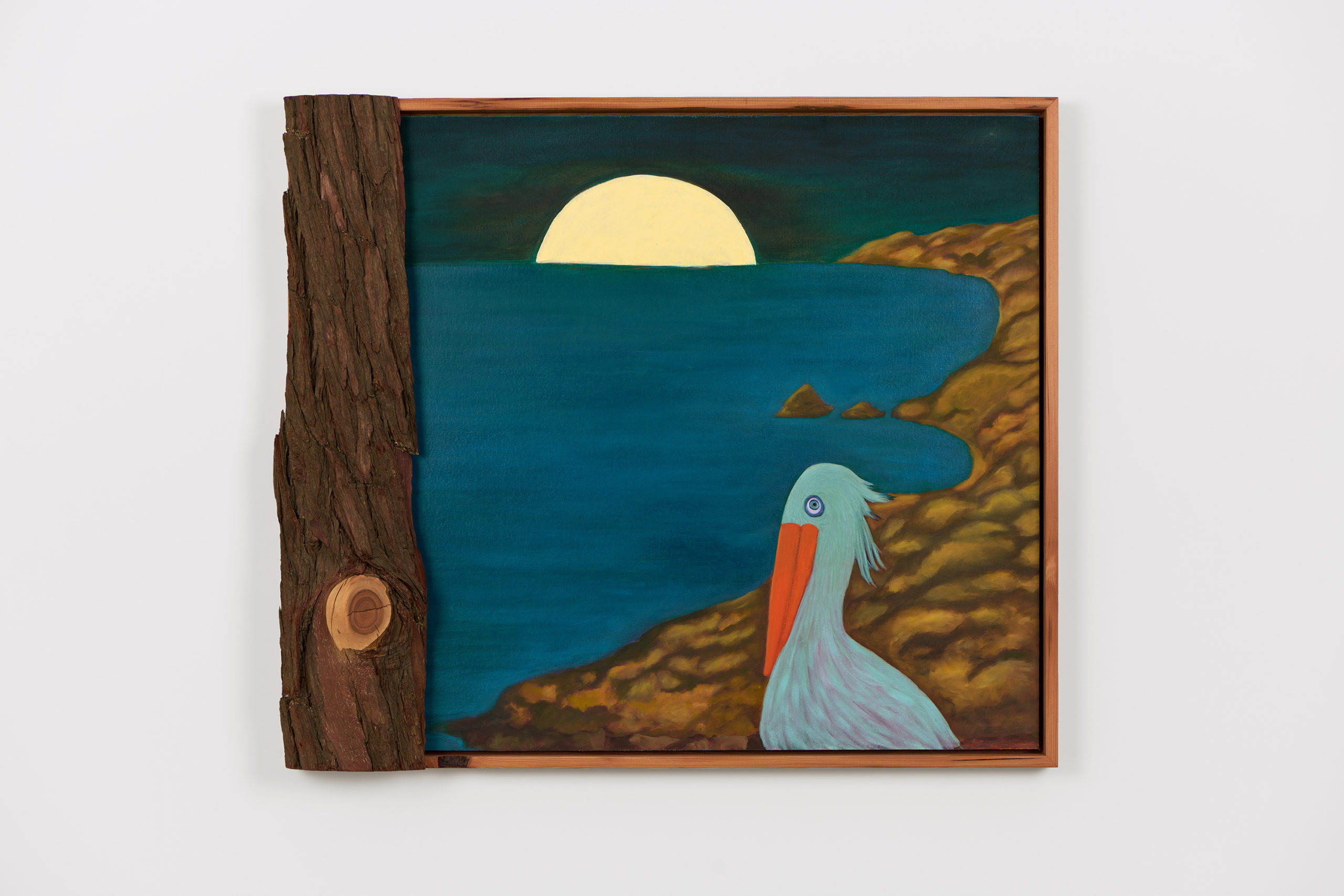

Stanya Kahn, Pelican, 2022. Oil on canvas with reclaimed old growth redwood frame and incense cedar inset, 35 ⅛ x 40 ⅜ x 2 ½ in. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

In 2018, the Woolsey Fire ripped through the Santa Monica Mountains, burning away most of Paramount Ranch’s Western Town. Gone were the saloon where shootouts began in Gunsmoke, the flimsy main street facades Jane Seymour trotted past in Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman, and the rickety porch where Evan Rachel Wood greeted her android father in Westworld.

At the center of town, across from a faux church that survived the fire, was the “Witness Tree,” so named for being present for so many film shoots and sharing the screen with legends like Cary Grant, Elvis Presley, and Marlene Dietrich. It was also humble, serving as the backdrop for wedding photos, the support for party piñatas, the meeting point for morning hikes. The Woolsey Fire scorched the oak’s enormous branches bare. By 2020, the National Park Service declared it dead. As with many Hollywood stars, the papers wrote obituaries, and the tree had a public funeral.

In an era of climate change, trees are dying faster than ever: smoked in wildfires, uprooted in floods, even clear-cut to build solar arrays. But the Witness Tree will live on. Its wood will be salvaged and reincorporated into Project Paramount, an effort to restore the town. In Los Angeles, other trees have found a second life in artworks by Glenn Kaino and Stanya Kahn, who leverage their trees’ respective reputations to comment on pertinent issues like prescribed burning, extraction, and climatic dystopia.

Glenn Kaino, A Forest for the Trees, 2022. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Aaron Mendez.

In a nondescript warehouse in the arts district, Glenn Kaino lined up redwood trunks plucked from a salvage yard to build A Forest for the Trees. The atmospheric installation, supported by SuperBlue (a producer of immersive art experiences) and The Atlantic magazine, is based on an editorial series The Atlantic published about federal lands. The audience walks along a footbridge through a small forest, stopping at expository, tree-themed, sometimes kinetic artworks, until they reach benches curving around an enormous fig.

Kaino’s didactic exhibition dives into the ramifications of the Weeks Act of 1911, which established our national park system but also legislated fire suppression across public and private lands. This effectively banned indigenous practices of ceremonial burning. Kaino’s forest places historic posters of Smokey Bear, guilting us to single-handedly prevent forest fires, with arguments pulled from The Atlantic’s reporting that Indigenous people stewarded the land far better than our federal system. For thousands of years, their intentional fires cleared out the excess dead, dry foliage that now fuels historically massive wildfires. A certain amount of flame helps free up space for germination, allowing our forests to replenish and expand, and replace the trees that have been lost. At the turn of the last century, however, the government was less concerned with the ripple effects of suppressing fires than with maximizing the timber supply for loggers.

Glenn Kaino, A Forest for the Trees, 2022. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Aaron Mendez.

Glenn Kaino, A Forest for the Trees, 2022. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Charley Gallay/Getty Images.

Kaino took advantage of our parasocial relationships with famous trees—specific ones, like the bristlecone pine Methuselah, and broad species, like the California Redwood—to endear them to the audience. He attached robotic faces to four of the redwoods so they could banter. One was voiced by the comedian Joel McHale, turning this anonymous trunk into a celebrity. Elsewhere in the forest, a spotlight shines upon a scale replica of Methuselah, one of the oldest trees in the world, who tries to explain complicated connections between the public policy, racism, industrialization, and climate change it has witnessed in its 4,800-plus years of life. The third starlet is the resurrected 144-year-old Moreton Bay Fig tree from Olvera Street, which collapsed from drought in 2019. Kaino found the remaining pieces of the tree and suspended its chopped-up branches in midair, then covered it in a mosaic of steel cubes and screens that flash to a song by Kittie Harloe.

Stanya Kahn, Forest for the Trees, installation view, Vielmetter Los Angeles, June 4–July 16, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

A Forest for the Trees can be sappy, but its heavy hitters of famed trees help communicate serious, and dense, information. For those who enjoyed the shade of Olvera Street’s fig trees, laying eyes on a friend that had been dead for three years could trigger weighty nostalgia. How long had it lain dismembered in a timber yard, waiting to be turned into something other than art? Stanya Kahn’s exhibition at Vielmetter Los Angeles, similarly titled Forest for the Trees, builds upon nostalgic thoughts like these. There, Kahn repurposed wooden planks and a dead tree she removed from her own property to build frames for wildlife paintings and plinths for porcelain sculptures.

Stanya Kahn, Forest for the Trees, installation view, Vielmetter Los Angeles, June 4–July 16, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Vielmetter Los Angeles. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

In colorful landscape paintings, Kahn imagines animals living undisturbed by human activity. A bright orange salamander clings to a mossy trunk, an albino moose foregrounds distant pines, and a pelican watches the moon rise over the ocean. Khan cradles her paintings in old growth redwood siding pulled from the garage that makes up her studio. Imperfect wheel-thrown porcelain vessels allude to ancient pottery unearthed in the Midwest. These objects rest upon shelves and plinths made from an incense cedar that collapsed in Kahn’s yard, suffocated from drought like the Olvera Street fig.

Though Kahn doesn’t recreate any famous trees, the salvaged wood embodies memories associated with those on her property. Kahn incorporated their remains into her show as one does when memorializing a loved one. Personal connection makes them mentors.

Glenn Kaino, A Forest for the Trees, 2022. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Charley Gallay/Getty Images.

If pop artists use celebrity to imbue their work with meaning, for Kaino and Kahn, the trees are the stars. Collective fondness for a certain tree, grown from its role in a film or its witnessing of your child’s first steps, could go as far as to earn it landmark status. In a world of intense, erratic weather and collapsing ecosystems, this emotional attachment could save their lives—and ours. X

Renée Reizman is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and educator based in Los Angeles.