The Dash column features brief, dense, hard-hitting, creative writing about art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. The dash is where the viewer comes to terms with what hit them. In what follows, writer Evan Kleekamp presents notes prompted by Cameron Rowland’s D37, on view at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, from October 14, 2018 through June 24, 2019.

Selfie with David Smith’s Cubi III, 1961, and Cameron Rowland’s 2015 MOCA REAL ESTATE ACQUISITION, 2018, at MOCA entrance. Photo: Evan Kleekamp.

Last July, I returned to the American heartland to attend a wedding. I took a train from the airport into Chicago. Heading toward the city, I counted the trees we passed on the side of the road. I had forgotten what it’s like to observe the landscape as a passenger. I stared at a line of trees that formed the edge of a wood until they receded from view. I don’t know why these trees caught my attention—I had passed them many times while riding to and from that same airport, on that same train. But this time, I became lightheaded. It dawned on me that trees in Middle America (cherry, oak, willow) grow much wider than those in the West (birch, cedar, pine). In this area, where the last recorded lynching took place in 1943, where police continue the local tradition of extrajudicial killings, the trees, I realized, were exceptionally suitable for hanging black people. A lynching I had seen in a photograph came to mind: a tree with a thick trunk and numerous branches proliferating in every direction; in the foreground, men and women, children in their arms, crowded around a dark-skinned body slung from a rope; liquid oozed from the figure’s groin and mouth; as was often the case, the body’s genitals and tongue had been hacked away, leaving only the soiled clothes to indicate its sex. Perhaps because my epiphany was located less in fact than experience, more in sensation than words, this image and its emanations left me searching for language. I wanted to say something about counterpoint, about the relationship between background and foreground, context and elision, affect and embodiment, time and the implements we use to measure it, the slippage between personhood and objecthood. But by then, in the crammed train car, the trees and the image were gone; I felt alone.

Cameron Rowland,

Tanaka Hedge Trimmer – Item: 0628-002770, 2018.

Tanaka Hedge Trimmer sold for $87.09,

10 x 35 x 10 inches (25.40 × 88.90 × 25.40 cm),

Rental at cost.

Stihl Gas Backpack Blower – Item: 0628-002765, 2018.

Stihl Gas Backpack Blower sold for $206,

18 x 25 x 43 inches (45.72 × 63.50 × 109.22 cm),

Rental at cost.

Stihl Backpack Blower – Item: 0514-005983, 2018.

Stihl Backpack Blower sold for $59,

21 x 35 x 19 inches (53.34 × 88.90 × 48.26 cm),

Rental at cost.

In the United States, property seized by the police is sold at police auction. Auction proceeds are used to fund the police. Civil asset forfeiture originated in the English Navigation Act of 1660. (1) The Navigation Acts were established to maintain the English monopoly on the triangular trade between England, West Africa, and the English colonies. (2) As Eric Williams writes, “Negroes, the most important export of Africa, and sugar, the most important export of the West Indies, were the principal commodities enumerated by the Navigation Laws.” (3) During the seventeenth century, the auction was standardized as a primary component of the triangle trade to sell slaves, goods produced by slaves, and eventually luxury goods. The auction remains widely used as a means to efficiently distribute goods for the best price. (4) Police, ICE, and CBP may retain from 80% to 100% of the revenue generated from the auction of seized property. Rental at cost: Artworks indicated as “Rental at cost” are not sold. Each of these artworks may be rented for 5 years for the total price realized at police auction.

1) Caleb Nelson, “The Constitutionality of Civil Forfeiture,” The Yale Law Journal 125, no. 8 (June 2016), https:// www.yalelawjournal.org/feature/the-constitutionality-of-civil-forfeiture. 2) Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1944), 56–57. 3) Williams, 57. 4) Brian Learmount, A History of the Auction (London: Barnard & Learmount, 1985), 30–31.

Courtesy of the artist and ESSEX STREET, New York.

Something similar happened when I walked into Cameron Rowland’s exhibition at MOCA, D37, and saw the bicycles, leaf blowers, and stroller grouped in the gallery. Rowland bought these objects from a private auction after they were seized through civil asset forfeiture. Given the region in which they were acquired, many no doubt come from undocumented Angelenos. The works, flanked by a grandfather clock stationed in the corner and a restrictive covenant posted on the southwest wall, left me struggling to describe the enigma at the core of the exhibition: how to assert the contemporary existence or afterlife of slavery?

Taking aim at discriminatory practices that disproportionately affect communities of color—such as dispossession, eminent domain, gentrification, mass incarceration, and redlining—D37 traces the legal status and economic value of these objects as they become the temporary property of the state. The Summer Infant 3D-One Stroller, for example, which Rowland acquired for one dollar, sells for almost $150 on Amazon; it may be rented from Rowland at the price he paid for five years at a time. Its auction value, less than one percent of its retail price, underscores its status as an asset that has been in intimate contact with an asset of another kind, the racialized body, whose depreciation it inherits like a stain.

Cameron Rowland,

Group of 11 Used Bikes – Item: 0281-007089, 2018.

Group of 11 Used Bikes sold for $287,

45 x 130 x 54 inches (114.30 × 330.20 × 137.16 cm),

Rental at cost.

In the United States, property seized by the police is sold at police auction. Auction proceeds are used to fund the police. Civil asset forfeiture originated in the English Navigation Act of 1660. (1) The Navigation Acts were established to maintain the English monopoly on the triangular trade between England, West Africa, and the English colonies. (2) As Eric Williams writes, “Negroes, the most important export of Africa, and sugar, the most important export of the West Indies, were the principal commodities enumerated by the Navigation Laws.” (3) During the seventeenth century, the auction was standardized as a primary component of the triangle trade to sell slaves, goods produced by slaves, and eventually luxury goods. The auction remains widely used as a means to efficiently distribute goods for the best price. (4) Police, ICE, and CBP may retain from 80% to 100% of the revenue generated from the auction of seized property. Rental at cost: Artworks indicated as “Rental at cost” are not sold. Each of these artworks may be rented for 5 years for the total price realized at police auction.

1) Caleb Nelson, “The Constitutionality of Civil Forfeiture,” The Yale Law Journal 125, no. 8 (June 2016), https:// www.yalelawjournal.org/feature/the-constitutionality-of-civil-forfeiture. 2) Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1944), 56–57. 3) Williams, 57. 4) Brian Learmount, A History of the Auction (London: Barnard & Learmount, 1985), 30–31.

Courtesy of the artist and ESSEX STREET, New York.

Like the bicycles, which Rowland acquired in clusters (8 bikes at $104, 11 bikes at $287), the stroller and its rental cost index the class and race relations, affective qualities, that brought the objects into police custody. (It should be no surprise that many of the bicycles, given their size and color, are meant for children. But the unfortunately rhetorical question remains: why are police seizing children’s bicycles?) Rowland places these objects alongside the grandfather clock and nineteenth-century receipts that track the taxes collected on property ranging from carriages, clocks, livestock, pianos, pistols, watches, and slaves; this arrangement suggests dispossession, beyond being compatible, is commensurate with the economic practices, legal frameworks, and ideology in which African slaves were traded as property. The spaces between these juxtaposed objects likewise intimate the disjunctions, gaps, and pauses that form the connective tissue between American slavery, civil asset forfeiture, and discrimination against undocumented peoples.

§

I am a black object. This is important to disclose when discussing Rowland’s show, since it expressly reminds viewers that black Americans were considered property until at least 1865. If Rowland’s assessment is correct, this property logic remains in place to this day. As with the bodies I imagined swaying from the trees as I passed, when I walked among the objects in the gallery, I considered myself among peers. Because unlike critics such as David Joselit, who has stated that Rowland withdraws from affect or expression, I believe these objects emit a hidden vitality, that they are fugitives.

Cameron Rowland,

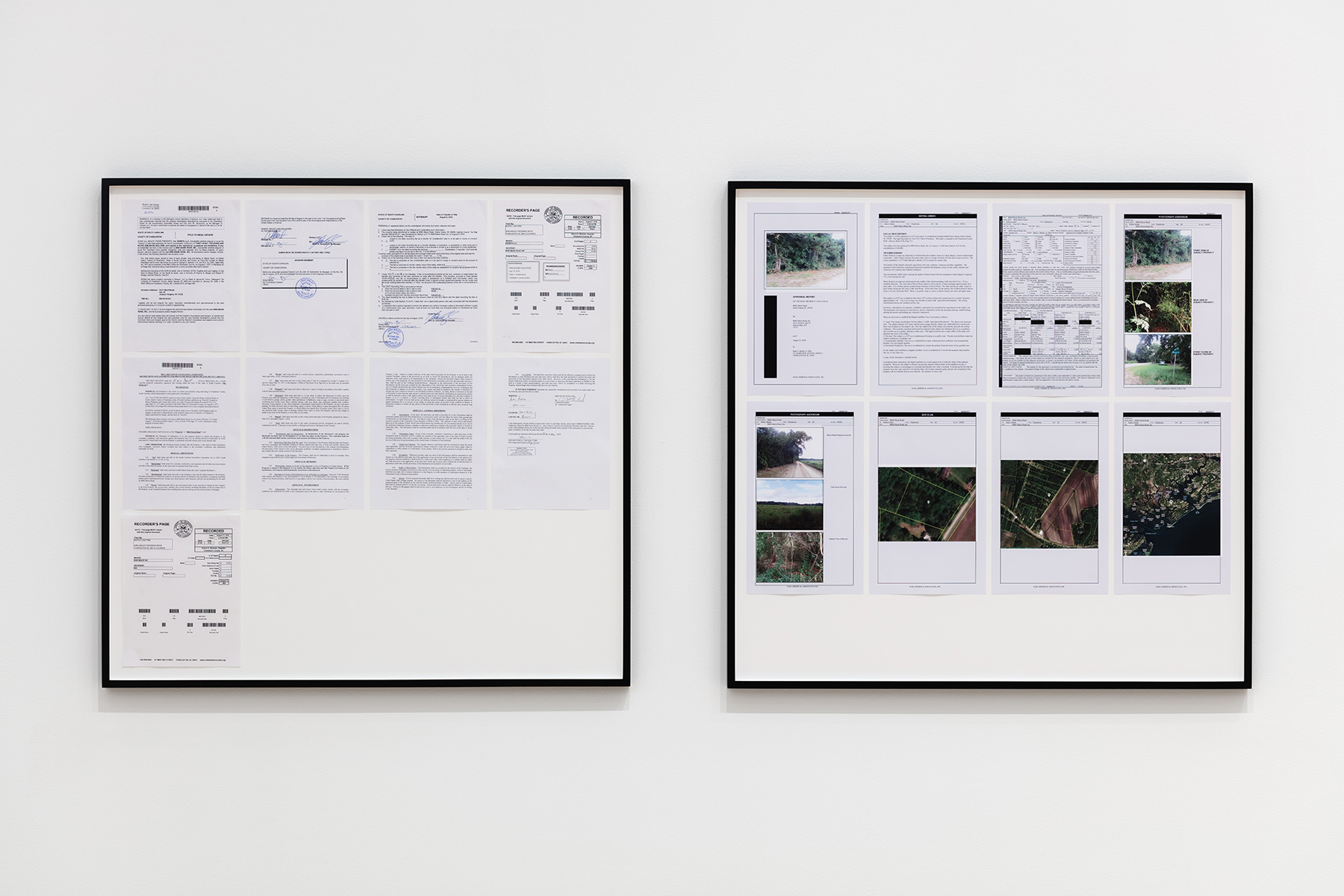

Depreciation, 2018,

Restrictive covenant; 1 acre on Edisto Island, South Carolina.

40 acres and a mule as reparations for slavery originates in General William Tecumseh Sherman’s Special Field Orders No. 15, issued on January 16, 1865. Sherman’s Field Order 15 was issued out of concern for a potential uprising of the thousands of ex-slaves who were following his army by the time it arrived in Savannah. (1) The field order stipulated that “The islands from Charleston south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the Saint Johns River, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States. Each family shall have a plot of not more than forty acres of tillable ground.” (2) This was followed by the formation of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in March 1865. In the months immediately following the issue of the field orders, approximately 40,000 former slaves settled in the area designated by Sherman on the basis of possessory title. (3) 10,000 of these former slaves were settled on Edisto Island, South Carolina. (4) In 1866, following Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson effectively rescinded Field Order 15 by ordering these lands be returned to their previous Confederate owners. Former slaves were given the option to work for their former masters as sharecroppers or be evicted. If evicted, former slaves could be arrested for homelessness under vagrancy clauses of the Black Codes. Those who refused to leave and refused to sign sharecrop contracts were threatened with arrest. Although restoration of the land to the previous Confederate owners was slowed in some cases by court challenges filed by ex-slaves, nearly all the land settled was returned by the 1870s. As Eric Foner writes, “Johnson had in effect abrogated the Confiscation Act and unilaterally amended the law creating the [Freedmen’s] Bureau. The idea of a Freedmen’s Bureau actively promoting black landownership had come to an abrupt end.” (5) The Freedmen’s Bureau agents became primary proponents of labor contracts inducting former slaves into the sharecropping system. (6) Among the lands that were repossessed in 1866 by former Confederate owners was the Maxcy Place plantation. “A group of freed people were at Maxcy Place in January 1866 …The people contracted to work for the proprietor, but no contract or list of names has been found.” (7) The one-acre piece of land at 8060 Maxie Road, Edisto Island, South Carolina, was part of the Maxcy Place plantation. This land was purchased at market value on August 6, 2018, by 8060 Maxie Road, Inc., a nonprofit company formed for the sole purpose of buying this land and recording a restrictive covenant on its use. This covenant has as its explicit purpose the restriction of all development and use of the property by the owner. The property is now appraised at $0. By rendering it legally unusable, this restrictive covenant eliminates the market value of the land. These restrictions run with the land, regardless of the owner. As such, they will last indefinitely. As reparation, this covenant asks how land might exist outside of the legal-economic regime of property that was instituted by slavery and colonization. Rather than redistributing the property, the restriction imposed on 8060 Maxie Road’s status as valuable and transactable real estate asserts antagonism to the regime of property as a means of reparation.

1) Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, updated ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1988; New York: HarperCollins, 2014), 71. 2) Headquarters Military Division of the Mississippi, Special Field Orders No. 15 (1865). 3) Foner, Reconstruction, 71. 4) Charles Spencer, Edisto Island 1861 to 2006: Ruin, Recovery and Rebirth (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2008), 87. 5) Foner, Reconstruction, 161. 6) Foner, 161. 7) Spencer, 95.

Courtesy of the artist and ESSEX STREET, New York.

The visual presence of a body is not the sole possibility for embodiment in a work, and should not be held as a criteria for assessing affect. Returning to my epiphany in the heartland—by which I mean the old heart of the country, the anyplace where slaves once lived—sometimes the slippage between contexts, felt more than seen, is the only way to understand the relationship between seemingly disparate phenomena. For me, this means acknowledging that the contextual frame is sometimes the only viable tool for bringing the invisible into view; it means acknowledging the authority Rowland rouses in his argument with dead men, men who recorded their laws in the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, laws that, because they set precedent, hold sway even if they are no longer in effect. That authority haunts me because it is indistinguishable from the authority Rowland challenges; in appropriating from the slave owner, the artist mimics the slave owner’s logic and his legal statutes. Meanwhile, the men in the trees issue no laws. Like the people whose dispossessed items Rowland exhibits, the law is something that has been done to them. The exhibited objects testify to the recurrent nature of this fact—absence, deletion, erasure as a visible effect—which they carry into perpetuity. x

Evan Kleekamp lives in Los Angeles, where they direct NOR Research Studio and Les Figues Press. Their writing has been featured in the Los Angeles Review of Books and SFMOMA’s online writing platform, Open Space.