The Dash column explores art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. The dash is where the viewer comes to terms with what they’ve seen. Here, Gracie Hadland takes a long look at images of Amy Winehouse, a pop star hunted to despair by the media, as rendered in the semaphore portraits by Bedros Yeretzian. His exhibition Enemies was on view at Commercial Street from January 7–February 6, 2022.

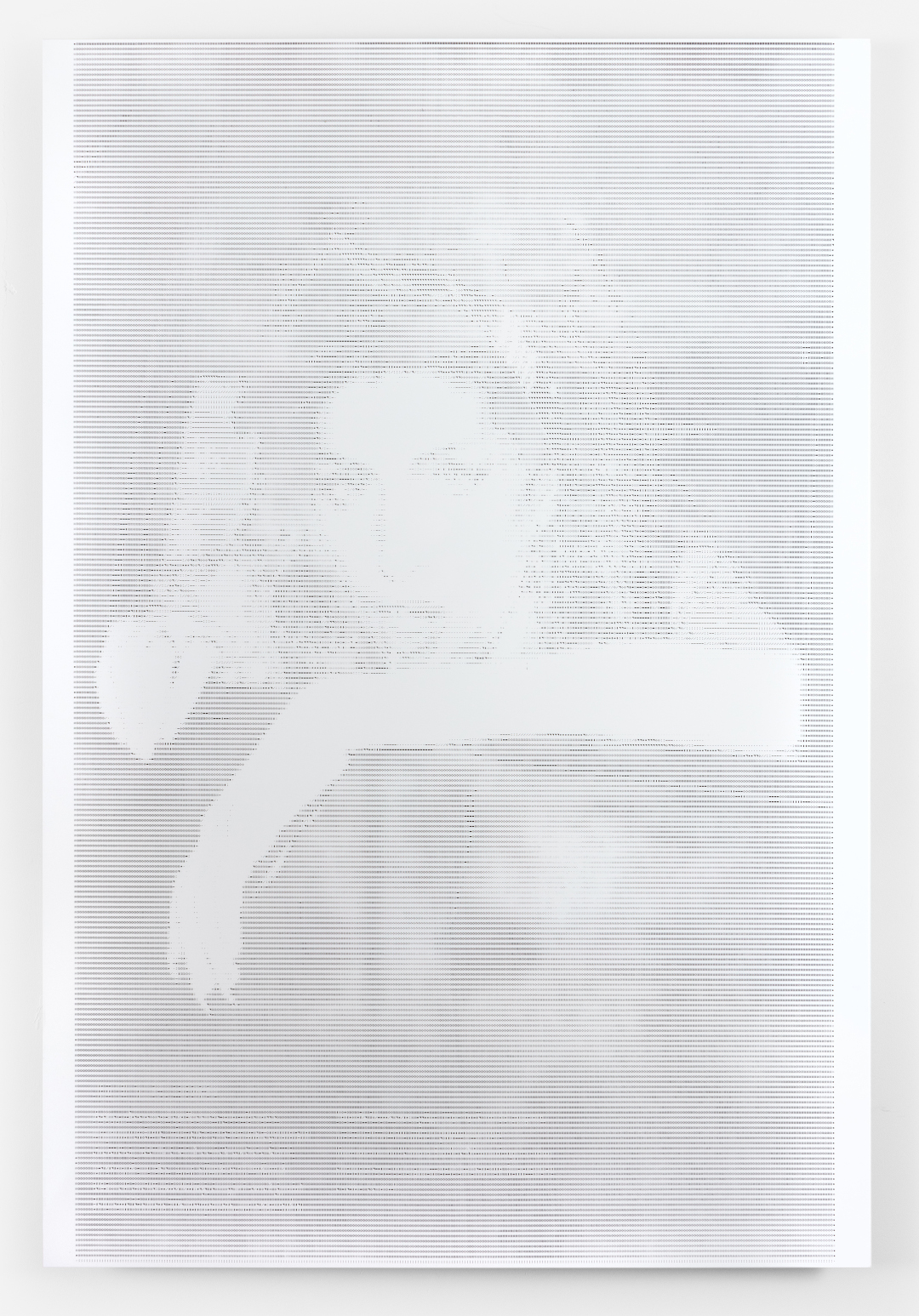

Bedros Yeretzian, Amy 5, 2021. Enamel on aluminum, 40 x 60 in. Courtesy of the artist and Commercial Street, Los Angeles. Photo: Morgan Waltz.

Whether they are images that are created in their mind’s eye or images others make of them, women are acutely aware of themselves as images. “Whilst she is walking across a room or whilst she is weeping at the death of her father,” writes John Berger, “she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking or weeping.” Berger, contrasting circumstances both mundane and dramatic, emphasizes the inescapability of this throughout Ways of Seeing (1972), pointing to the conditions of a culture that exploits a woman’s image as a commodity. Indeed, a number of women have died tragically because of the demand for visual access to celebrities, whether driven to drugs and madness by the psychological effects of fame or literally killed by a carful of photographers trying to take her photo.

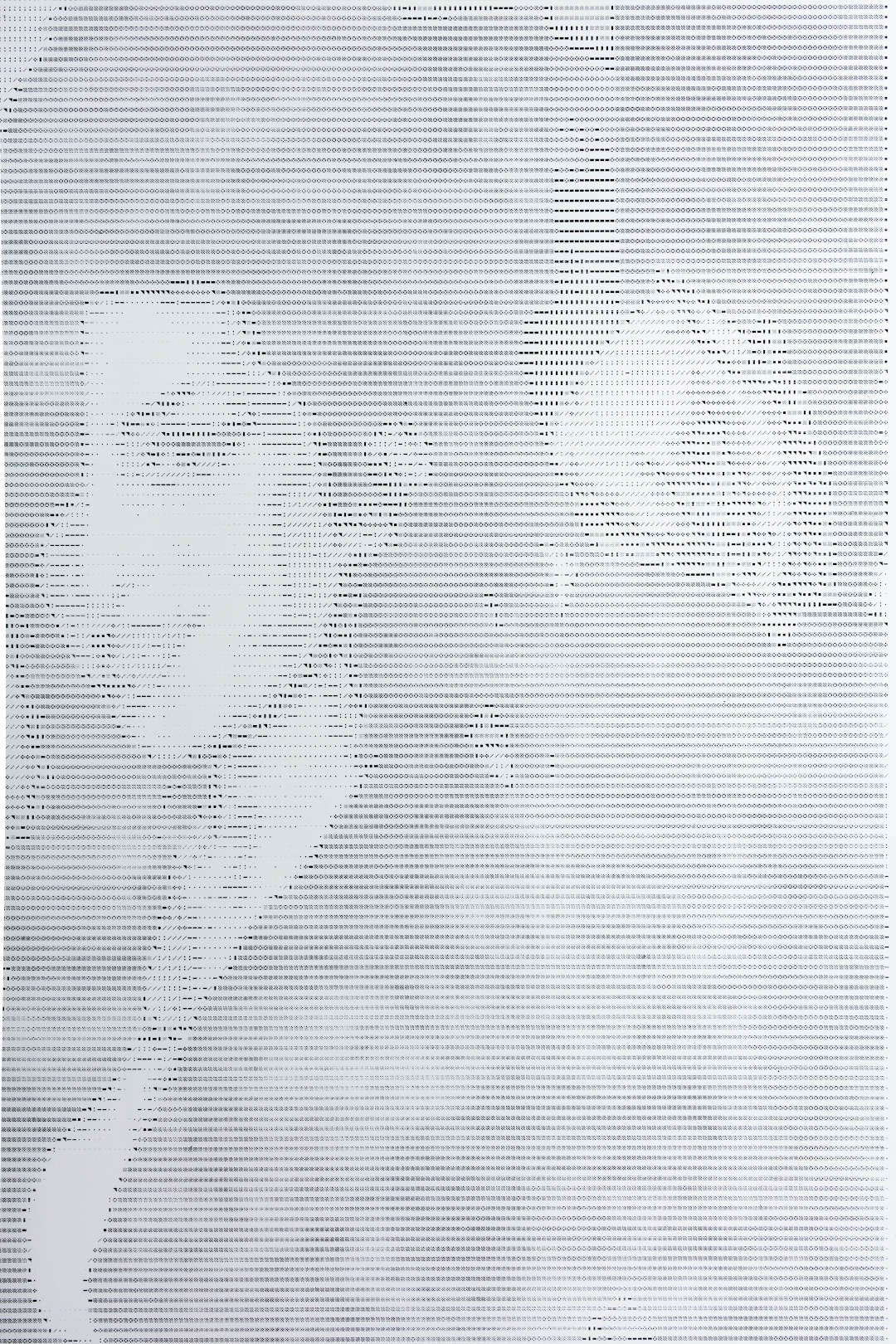

For Enemies, his exhibition at Commercial Street in Hollywood, Bedros Yeretzian has chosen one of these tragic female figures as his subject: the late British singer Amy Winehouse, who drank herself to death at the age of 27. In the gallery, there are seven enamel prints on aluminum of paparazzi photos of Winehouse, walking down the street with her exaggerated rockabilly look or leaning out of a car window dangling her long acrylic nails. The works are about the size of movie posters lining the walls of a theater lobby. The black-and-white images resemble faded newspaper images, highly pixelated. Up close, they are abstract; they are only legible as her image from a distance. Slightly forensic, resembling a crude facial recognition technology, the images have been processed through an open-source image generator so that each “pixel” is one of the International Code of Symbols, a series of signs used by ships to communicate via flags. The code is mostly used in crucial moments to indicate things like “I need the Coast Guard” or “I need immediate medical attention.” Yeretzian provokes a tension between the two sets of images: maritime signals and pop stars. Given Winehouse’s exploitation by the press, and thus her strained relationship to her own image—which one could argue was the driver of her demise—Yeretzian has reconstituted Winehouse’s image as a call for help.

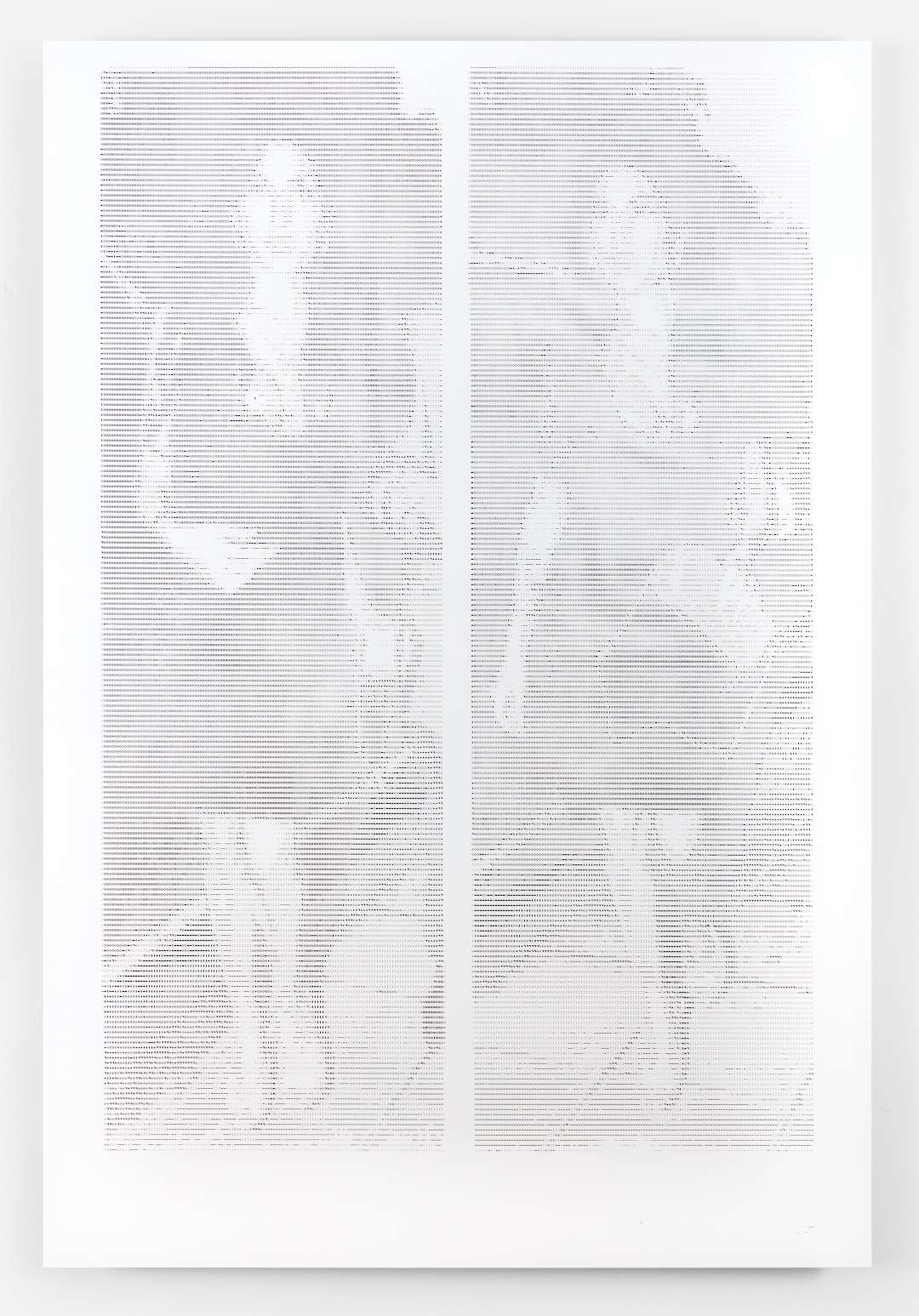

Bedros Yeretzian, Amy 5, 2021. Details. Enamel on aluminum, 40 x 60 in. Courtesy of the artist and Commercial Street, Los Angeles. Photo: Morgan Waltz.

The paparazzi was at its height in the mid-2000s, celebrity breakdowns blazoned with a kind of tawdry drama. Winehouse was one of the last victims of this golden age, just when the industry was becoming increasingly gratuitous and macabre. A paradigmatic shift in the way celebrities relate to the media, and thus the public, occurred. The internet, social media, and smartphones have outmoded the need for dedicated, professional paparazzi. A photograph of a celebrity no longer has the value it may once have had, because, more likely than not, she is photographing and posting it herself. What was once a stolen image is now a willingly shared product. Or else, celebrities hire their own photographers and art directors to direct paparazzi-style shoots: see Julia Fox and Kanye West’s photoshoots in January 2022, styled by Interview magazine. Their public coupling itself was far beyond a media stunt, dissolving into a blurry space between reality and fiction. Randomness and candidness are staged, and the resulting images have been tweaked by multiple filters and PR teams. The control famous people have over their “image” might indicate a larger class divide over control and production of images. The trajectory of fame begins where one craves exposure, witnesses, and media attention, and ends where one craves privacy, isolation, and control of one’s appearance. The rest of us have less access to privacy, constantly being surveilled online, producing data for tech companies. Privacy is a luxury.

Bedros Yeretzian, Amy 4, 2021. Enamel on aluminum, 40 x 60 in. Courtesy of the artist and Commercial Street, Los Angeles. Photo: Morgan Waltz.

This businesslike control makes us nostalgic for the tabloid heyday of the mid 2000s and its frenzied mill of rumors and grainy images. We long for an organic, spontaneous, and perversely invasive look into the lives of disturbed famous people rather than a scrubbed, made-to-order photoshoot with only the illusion of access. We miss the possibility of accidents, of stumbling upon the million-dollar image. We feel less like voyeurs and more like consumers. The ubiquity, and quantity, of famous people has made them less iconographic and more familiar, redundant, and banal. Fewer images of them would mean more value based on their uniqueness. They would become more established as icons; one might associate a single image with a single figure.

Yeretzian focuses on the relationship between performer and audience, and the element of distance inherent in that relationship. If the works are viewed from far away, Winehouse appears; but close up one sees only squares and lines, a series of symbols only legible to sailors. In some sections of the works, there are just little black marks, portions of a symbol not fully illustrated. They get fainter and fainter, rendering the most exposed parts of the image as negative space. The mind leaps to interpolate the gaps in the image as well as the distance between the viewer and the object. The works only exist as icons from a distance, as products of projection. The result is melancholic, Winehouse’s absence felt: from the room, from the world. What’s left are these hazy images of her likenesses but the irony is that, for those who didn’t know her, that’s all there ever was. Perhaps even her friends felt the same. Yeretzian captures the distances between fan and celebrity, audience and performer; the works are images of the false intimacy of projection.

Enemies, installation view, Commercial Street, Los Angeles, January 7–February 6, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Commercial Street. Photo: Morgan Waltz.

In the vein of a pop artist, Yeretzian positions himself as a fan, maker, and interpreter of culture. “We are always looking at the relationship between things and ourselves,” Berger writes, as if to say that subjectivity and interpretation occur in this distance. In the gallery, the viewer can choose to move close or stay back; their phenomenological autonomy defines the meaning derived from the image. In one view of the works, the meaning is muddled, harder to read. The ISC symbols link language and the pictorial in order for international ships to communicate without words. In a way, they function as images. But Yeretzian’s work renders both tools futile or emphasizes their limitations: the ISC can only communicate certain messages and the images are only a representation of Winehouse, not the woman herself.

Bedros Yeretzian, Amy 2, 2021. Enamel on aluminum, 40 x 60 in. Courtesy of the artist and Commercial Street, Los Angeles. Photo: Morgan Waltz.

The tabloids notoriously pursued Amy at the height of her disintegration, in and out of hospitals, rehabs, and jails. She was frequently photographed in states of duress: drunk and high, after a night out, with her makeup smudged, crying, mouth open, yelling at photographers to leave her alone. The kind of self-awareness Berger talks about was heightened and literalized, practically weaponized against Winehouse, based on the conditions of a world that exploits women often as a commodified image. But Yeretzian has chosen images in which Winehouse, while shielding herself from the camera, looks less sickly and more glamorous. Her eyes held down moving swiftly through a crowd, her hand in her hair and a cigarette in her mouth. Like an adoring fan offering an act of vengeance on Winehouse’s behalf, Yeretzian lets her have the last word. x

Gracie Hadland is a writer in Los Angeles.