Umar Rashid reimagines contemporary history—particularly the saga of the fictional Frenglish Empire. Through this fabrication, Rashid becomes the community griot or shaman, a harbinger of realities that were forgotten or erased but might reenter the matrix through the portal of his artistic practice. The title of a multimedia sculpture from 2022, a jumbotron envisioned as a missive from space, attests to that project’s urgency: Sink or Synchronize. The voice from the outer realm of the cosmic overlord that compels you. I spoke with Rashid in a Thai restaurant across the street from MoMA PS1 after visiting Ancien Regime Change 4, 5, and 6, his solo show on view at the museum September 22, 2022–March 13, 2023.

Umar Rashid, Messier object 66 and the warrior who slew the basilisk and damaged Mission Control. Ad Astra., 2022. Acrylic and ink on canvas, 72 × 84 in. Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo. Photo: Josh Schaedel.

EMANN ODUFU: This isn’t my first time interviewing you. We spoke in 2021, during part one of the “Ancien Regime Change” series. For years you have been working on creating this Frenglish narrative, which is a conglomeration of the French and English empires and their power struggle to maintain control of their territories along the east coast of North America. You also have another branch of the narrative based on the West coast and in the Southern states around the Spanish mission system, which you ironically call “Mission Control.” Your alternate history starts somewhere in the 1600’s and ends in the 1800’s and has largely focused on the United States, but you are increasingly basing stories in Europe, Africa, and Asia. Can you give some clarity into the state of mind required to create work based in this epic alternate reality?

UMAR RASHID: It helps to be certifiably insane to create the worlds I create. Also, it helps that I’m a nonlinear thinker. I go through periods where I absorb massive amounts of information and I process it through just living. I’ve always created worlds because I was always unhappy with the world in which I exist. I’ve been working on this narrative for about 20 years. This story is so expansive that I don’t think I’ll complete the story in my lifetime. It’s literally one small tale within another small tale, and this show at PS1 is just a microscopic rendering of that narrative.

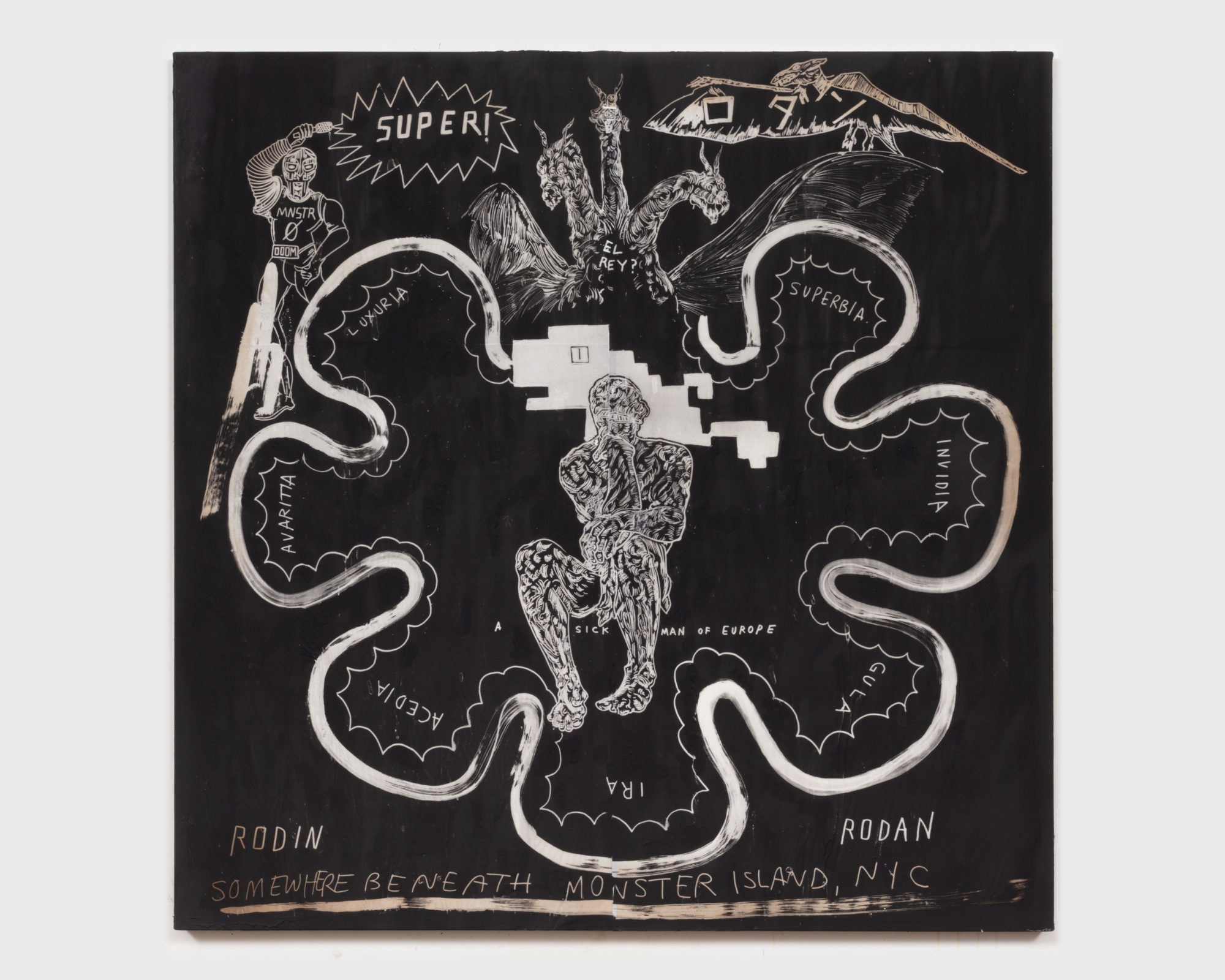

Umar Rashid, A Protean map of the 5 boroughs of Novum Eboracum (New York City) in the death throes of a popular, yet complicated revolution. 1798. Or, Monster Island., 2022. Ink, coffee, and tea on paper, 51¼ x 47¾ in. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo. Photo: Sai Tripathi.

Umar Rashid, 4:18. Divine Rule. Eric B. is president at last., 2022. Acrylic and ink on canvas, 48 × 48 in. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo. Photo: Josh Schaedel.

EO: I see the type of work you create and how grounded it is in storytelling and mythology as being similar to the poet Ishmael Reed, mainly the synchronicity between many different schools of thought in both of your works.

UR: The people who are the pioneers aren’t the pioneers. We’re all part of this collective energy that builds and builds and builds. I’m a storyteller first. I come from a theater background. My father teaches theater. I also come from a hip-hop background. I’ve rapped for many years. My work is an amalgamation of everything I do and all the things I’ve been influenced by, so if that suggests comparisons to Ishmael Reed or someone else in the firmament doing something similar, then so be it.

Umar Rashid, Sink or Synchronize. The voice from the outer realm of the cosmic overlord that compels you, 2022. Mixed media. Installation view, Umar Rashid: Ancien Regime Change 4, 5, and 6. MoMA PS1, Queens, NY, September 22, 2022–March 13, 2023. Courtesy of MoMA PS1. Photo: Steven Paneccasio.

EO: Revolution plays a vital role in the current show. Earlier in Ancien Regime Change there was a transfer of control of New York City from the Dutch to the Frenglish. In your show at PS1, Frenglish power is threatened by the growth of a rebel army led by President Lord Eric B., the famed rapper from the real-world 1980s. It culminates in Eric B. surrendering to Frenglish soldiers. The last room goes in a different direction. It depicts a cataclysmic event that brings the show into a cosmic and fantastical space. Can you tell me about the multimedia sculpture and video installation Sink or Synchronize. The voice from the outer realm of the cosmic overlord that compels you (2022)? How does it connect to the larger story?

UR: As an African American philosopher of the twentieth century, Sir Beanie Siegel said, you can “get down or lay down.” “Sink or synchronize” means to get down or lay down. Then there’s also a way that the word “sink” means synchronizing: to sync is to be one with, or you can sink as in to go down below, or as in “everything and the kitchen sink.”

The whole concept behind the multimedia sculpture, which takes the shape of a Jumbotron, is about how we view the world through screens and live through screens. A Jumbotron is usually seen at a sports event. War is almost like a sporting event now, especially when looking at Russia and Ukraine. The Jumbotron is the actual spectacle at the game. Maybe more people look at what’s happening on the Jumbotron than at the actual game. It’s like the magician’s hand. So this Jumbotron is passing in the firmament, and it crash lands on Earth. While most of the show unfolds on Earth, there is also a war off in space between conflicting schools of cosmology. The work Messier Object 66 (2022), behind Sink or Synchronize, depicts this Afro-Caribbean Indigenous brother on a zebra that resembles a space Pegasus. He is fighting the church out in space for control of the belief systems of the people on Earth.

Umar Rashid: Ancien Regime Change 4, 5, and 6. MoMA PS1, Queens, NY, September 22, 2022–March 13, 2023. Courtesy MoMA PS1. Photo: Steven Paneccasio.

Umar Rashid, Battle flag of Frengland, 2010. Cotton and brass rivets, 48 x 36 in. Courtesy of the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo. Photo: Josh Schaedel.

EO: Saidiya Hartman’s term “critical fabulation,” coined in her 2008 essay “Venus in Two Acts,” refers to a style of creative semi-nonfiction and hard research that surfaces suppressed voices of the past. Because narratives around people of color have been coopted and hidden, the only way for cultural creators to tap into these forgotten histories is to create their own narratives. I think your work falls within the category of this term.

UR: I started this whole thing in 2003. I was already doing it when she coined that term, but it fits. It fits a lot more than being under the big white umbrella of Afrofuturism. It’s a very apt term for what I do because, as you said, the history of the world has been such that you got to make up a few things. I’m pretty sure Europeans take the historical narrative and put their own flourish on it. That’s why I have a hard time saying white supremacy because I don’t believe that white people are inherently supreme, and words are wind, but they can also lock you into a mindset. Critical fabulation is good because it gives you a way out. x

Umar Rashid lives and works in Los Angeles. He received his BA in cinema and photography from Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. His work was featured at the Huntington and the Hammer Museum as part of the biennial Made in LA 2020: a version.

Emann Odufu is an art activist, independent filmmaker, producer, screenwriter and digital media specialist hailing from Newark, New Jersey.