Professor of French Literature Denis Hollier once wrote, “Whereas it is possible to see without being seen, it is not possible to touch without at the same time being touched. One never emerges intact from any contact.” Artist Diane Severin Nguyen puts this proposition to the test with her latest photographs. eXhibitions strives to bring the conversation to the artworks, and X-TRA’s Kyle Thomas Hinton met Nguyen at Bad Reputation in Los Angeles to discuss her show Flesh Before Body, on view until March 9, 2019. The following has been edited for length and clarity.

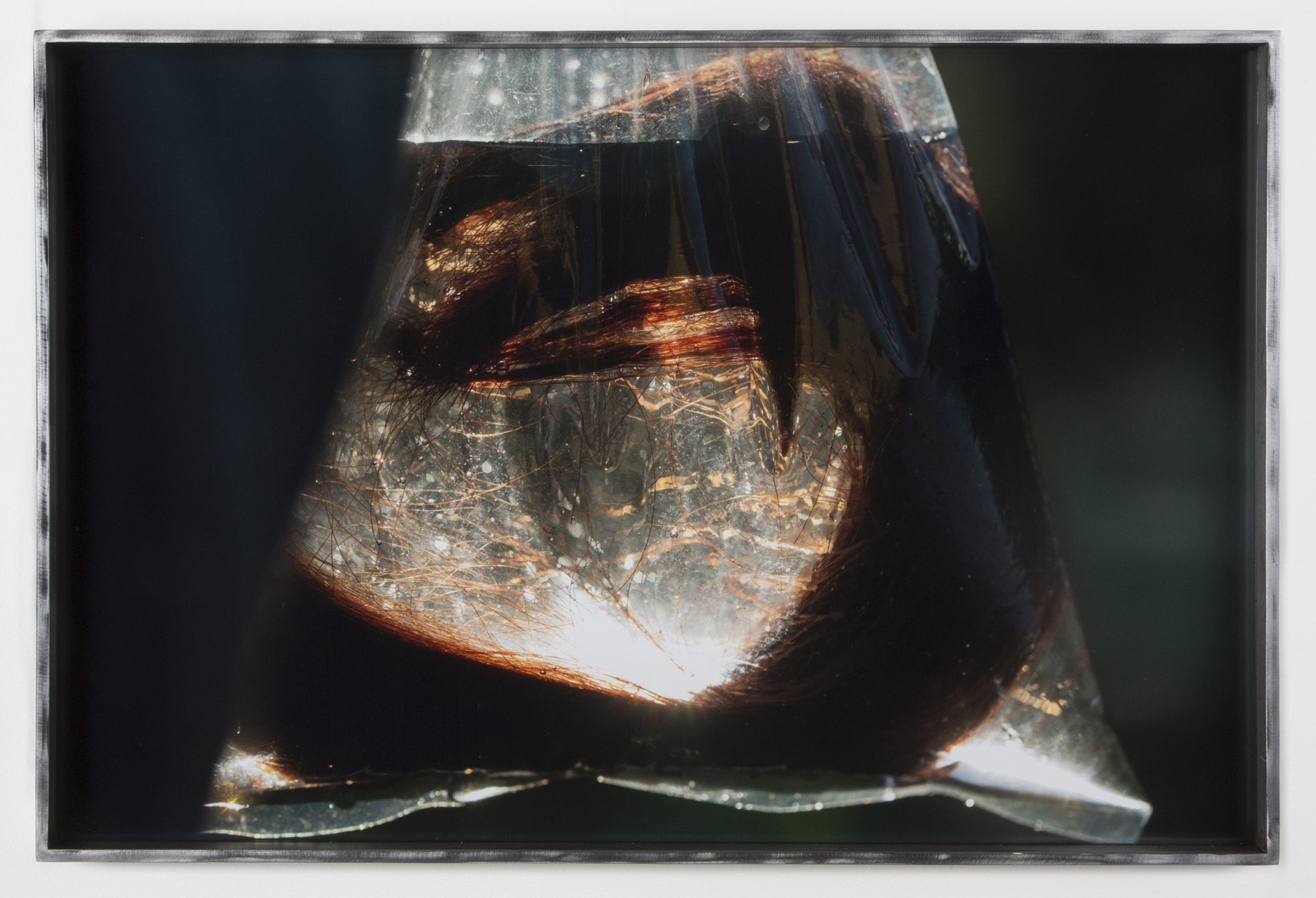

Diane Severin Nguyen, Liquid Isolation, 2019. LightJet chromogenic print, artist frame, 15 x 22.5 in. Courtesy of the artist and Bad Reputation, Los Angeles. Photo: Bad Reputation.

DIANE SEVERIN NGUYEN: There are so many entry points to how I think about my work. I’m deciphering photography as symbolic language, and I’m trying to subvert the essentialism of that index. I never think that a photograph can celebrate a life, or fully contextualize a life in any way. And I believe that the attempts to assign one’s entire identity in an optic way is problematic. The only thing a photograph can do, if anything, is maybe celebrate death. But it definitely cannot convey life. I think that’s also why I work from the place of non-life or still life. I feel like I have to start there in order to understand how a photograph attempts that construction.

KYLE THOMAS HINTON: I’m really interested in that kind of conception. François Laruelle has this idea of a photo-fiction, where the photograph is insufficient instead of being an essential or dialectical thing, so it can never properly will truth or power to the idea of a life. The photograph can only ever be a kind of failure, in a sense, to properly demonstrate what a life might be or what a life could be.

DSN: Even in terms of emotional affect it seems like I’m rearranging failure. My process is incredibly defined by failure. Everything surrounding that one moment—to use photographic terminology, the decisive moment—is surrounded by failure. It seems like a really important dialogue to me, the things that I can’t convey.

KTH: I think within your work there’s a capaciousness to that failure. With regard to the materials you use, it’s not that it’s a celebration of inorganic over organic or vice-versa, or further claims to binary thought, it’s that the object could be both and neither.

DSN: I reference a lot of subjective and photographic terminologies surrounding the image. And I like to look at the points in which they both conflate and deflate each other. It’s kind of a conversional process. For instance, I often find myself making and photographing fake wounds, like in Pain Portal (2019). In a way, it’s a reference to the punctum of a photograph, right? And if so, does the punctum emerge through some random, romantic idea of chance? Or does it have to rely on some moment of supposedly real pain within a social space? What does it mean to photograph someone’s pain? Can pain be conveyed through an image? Can you be affected without having experienced the thing itself? I hope that the work can point to methods of constructing pain for consumption.

Without being grandiose, I think the most basic question I’m asking in my work is if one can be touched without having to touch. That’s what we implicitly demand from images. So when I create a fake wound, I’m also questioning if pain could ever be transmitted in such an excessively symbolic way. Who can feel pain? How is that transmitted? What does it look like? I think there’s something lingering in my images in that way… this idea of the capture of a suspended moment. I try to enact these things literally. There’s a certain melodrama to it, but the whole point is that I’ve constructed everything, and the image is supposed to exude that overconstruction. It speaks to the absurdity of such an index.

Left to right: Diane Severin Nguyen, Co-dependent exile, 2019. LightJet chromogenic print, artist frame, 15 x 10 in. Installation view, Flesh Before Body, Bad Reputation, Los Angeles, January 26 – March 9, 2019. Pain Portal, 2019. LightJet chromogenic print, artist frame, 15 x 10 in. Courtesy of the artist and Bad Reputation, Los Angeles. Photos: Bad Reputation.

KTH: It’s interesting that within your work everything is hyper-constructed, like in Co-dependent exile (2019) where you’ve tied hard candy to twine. Your hand is always in it, but simultaneously everything is indeterminate, like a quantum superposition where different states of being coexist simultaneously. There’s an immanence where all potential interpretations are already there within the image. I’m also really interested in Pain Portal for that reason. I think something you explore with that work and throughout the show is the idea of the empathetic image, which is always its own limit…

DSN: I would say that there’s a limit to it, but that the equivalence is always warped. I feel like with the hyper-textural, visceral reality that I’m creating, how it’s meant to act phenomenologically isn’t supposed to feel exactly like how it felt when I was making it. The tactility happens within the translation, kind of like autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR). It’s about non-catharsis. The feeling that you’re getting is feeling through alienation. My work isn’t meant to be this immersive experience, necessarily. I’m not trying to drown you in this slime and make you feel that. It’s more the fact that you can’t touch it. I’m interested in that distance.

KTH: Like the impossibility of a relation to the photograph?

DSN: Yeah. Again, the experience is non-cathartic. I’m interested in that state of suspension. ASMR isn’t about orgasm, it’s about impotence to a large extent, and the intimacy of it is based upon not having to be there, yet feeling something. It’s intimacy instigated by distance. So I try to think about how physical tension is held in this way, how it takes on the gap of not being there.

KTH: So both the beauty of the work but also the dereliction is that one can only ever have a broken or improper relation to the photograph?

DSN: Because the photograph is flattened. So, what kind of new experience can one have when it’s flattened? It’s a transfiguration in the way that it points to a reality in between a definitive moment and a potential moment. That time-space is something I’m very interested in, because that points to a self that can be tethered materially, but at the same time is immaterial and abstracted.

KTH: So your work is both within and without the realm of optics?

DSN: There’s a transference of subjectivity or an identification with the object. I think the idea of a boundless self that can identify with all things is a spiritual clarity but also motions towards an experience of trauma. You’re here in your body, but then you’re also somewhere else, intensely. I think about the rendering of trauma in that sense, as an image.

Left to right: Diane Severin Nguyen, Wilting Helix, 2019. LightJet chromogenic print, artist frame, 15 x 10 in. Installation view, Flesh Before Body, Bad Reputation, Los Angeles, January 26 – March 9, 2019. Malignant tremor, 2019. LightJet chromogenic print, artist frame, 15 x 10 in. Courtesy of the artist and Bad Reputation, Los Angeles. Photos: Bad Reputation.

KTH: So it’s this traversing of space-time but it’s not necessarily lived for a specific future? It just kind of is, precisely because the object is without time and it can move freely. If the viewer is to encounter your work knowing they can only possess a distant or an improper relation, then what does that mean for both the essence and position of the image? Historically the photograph has served to redeem a limited imaginary capacity through representation. With the image failing to represent itself, then it would be released from any presupposed doctrine or command…

DSN: While I believe that everything can be referenced within the image-plane, it’s not about some holistic redemption within that space. To me, the broken relation is a precarious but somewhat eternal position. This broken-ness is something I’m implying visually without having to break or alter the physical plane of the print. I don’t want an allegory built around process. This is a state of being that isn’t looking for an origin point or justification in the real. I think that most people don’t get to live within the faith of, “this is the real, this is the origin point, this is what happened.” It’s much more this constant negotiation, or a certain alertness to meanings that could shift.

KTH: Maybe it’s like a plenum in physics, where a space is full of matter and infinite possibilities… This is where the conversation about the indexical image, or the thing that is represented, and the platitudes about utopia or dystopia are interesting. I would approach your work rather in terms of atopia, or placelessness, where the thing can be everywhere precisely because it is nowhere.

DSN: I see each of the images in this show operating simultaneously as a camera, within the narratives of the material relationships. Liquid Isolation (2019), which images human hair suspended in a bag of water, forces the camera to admit to its own immersion, as facilitating containment and absorption, rather than being a dry, offshore observer. There’s an illusion of dryness in photography, or the reliance of the camera on being dry, watching from some distance, but it’s the only medium where you can actually capture what liquids look like. It can capture liquidity in exceeding detail, as well as other temporary states of being. I feel like these temporary states of being as they are “captured”—that is the violence of indexical photography because it pins down the fugitive subject. That’s problematic in a way that is productive to me. I like the idea of collapsing that binary between the apparatus and the image itself, or the image’s product. I think that these images come out of a documentary lineage, which is very violent. I’m working within the provisional moment, the waiting-for-something-to-happen, and I compose my images with these strategies, but to totally defunct ends. x

Diane Severin Nguyen was born in 1990 in Carson, CA. She lives and works in Los Angeles. Nguyen completed her BA from Virginia Commonwealth University (2013) and is an MFA candidate at the Milton Avery School of the Arts, Bard College (2019). In addition to her current show at Bad Reputation, Nguyen is part of a two-person show at Bureau, New York.

Kyle Thomas Hinton is a writer and poet based in Los Angeles.